Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2025-02-24

Date: 2024-04-22

Date: 2024-04-25

|

This second type of free variation can also be seen as constituting the tip of a much larger theoretical iceberg. In the [ε]conomic – [i]conomic cases, two otherwise contrastive sounds are both possible in a single word. The contrast between two phonemes may also be interrupted more systematically, in a particular phonological context; in this case, rather than the two phonemes being equally possible alternatives, we find some form intermediate between the two.

One example involves the voiceless and voiced English plosives. These seem to contrast in all possible positions in the word: minimal pairs can be found for /t/ and /d/ initially, as in till versus dill; medially, in matter versus madder; finally, as in lit versus lid; and in consonant clusters, as in trill, font versus drill, fond – and the same is true for the labial and velar plosives. However, no contrast is possible in an initial cluster, after /s/: spill, still and skill are perfectly normal English words, but there is no *sbill, *sdill or *sgill. This phenomenon is known as neutralization, because the otherwise robust and regular contrast between two sets of phonemes is neutralized, or suspended, in a particular context – in this case, after /s/.

In fact, matters are slightly more complicated yet. Although the spelling might suggest that the sounds found after /s/ are realizations of the voiceless stops, we have already seen that, in one crucial respect, they do not behave as we would expect voiceless stops to behave at the beginning of a word: that is, they are not aspirated. On the other hand, they do not behave like realizations of /b d g/ either, since they are not voiced. That is to say, the whatever-it-is that appears after /s/ has something in common with both /p/ and /b/, or /t/ and /d/, or /k/ and /g /, being an oral plosive of a particular place of articulation. But in another sense, it is neither one nor the other, since it lacks aspiration, which is the distinctive phonetic characteristic of an initial voiceless stop, and it also lacks voicing, the main signature of an initial voiced one.

There are two further pieces of evidence, one practical and the other theoretical, in support of the in-between status of the sounds following /s/. If a recording is made of spill, still, skill, the [s] is erased, and the remaining portion is played to native speakers of English, they find it difficult to tell whether the words are pill, till, kill, or bill, dill, gill. Furthermore, we might argue that a /t/ is a /t/ because it contrasts with /d/ – phonemes are defined by the other phonemes in the system they belong to. To take an analogy, again from written English, children learning to write often have difficulty in placing the loop for a right at the base of the upstroke, and it sometimes appears a little higher than in adult writing – which is fine, as long as it doesn’t migrate so high as to be mistaken for a

right at the base of the upstroke, and it sometimes appears a little higher than in adult writing – which is fine, as long as it doesn’t migrate so high as to be mistaken for a , where the loop is meant to appear at the top. What matters is maintaining distinctness between the two; and the same is true in speech, where a realization of /d/, for instance, can be more or less voiced in different circumstances, as long as it does not become confused with realizations of /t/. In a case where the two cannot possibly contrast, as after /s/ in English, /t/ cannot be defined as it normally is, precisely because here alone, it does not contrast with /d/. It follows again that the voiceless, unaspirated sound after /s/ in still cannot be a normal allophone of /t/.

, where the loop is meant to appear at the top. What matters is maintaining distinctness between the two; and the same is true in speech, where a realization of /d/, for instance, can be more or less voiced in different circumstances, as long as it does not become confused with realizations of /t/. In a case where the two cannot possibly contrast, as after /s/ in English, /t/ cannot be defined as it normally is, precisely because here alone, it does not contrast with /d/. It follows again that the voiceless, unaspirated sound after /s/ in still cannot be a normal allophone of /t/.

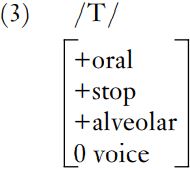

Phonologists call the unit found in a position of neutralization an archiphoneme. The archiphoneme is symbolized by a capital letter, and is composed of all the properties which the neutralized phonemes have in common, but not the properties which typically distinguish them, as shown in (3).

The archiphoneme /T/ is proposed where the normal opposition between /t/ and /d/ is suspended, so neither /t/ nor /d/ is a possibility. /T/ is an intermediate form, sharing the feature values common to /t/ and /d/, but with no value possible for voicing, since there is no contrast of voiced and voiceless in this context. Neutralization is therefore the defective distribution of a class of phonemes, involving a particular phonological context (rather than a single word, as in the either/neither case).

There are many other cases of neutralization in English, but for the time being, we shall consider only one. In many varieties of English, the normal contrasts between vowels break down before /r/. To take one example, British English speakers will tend to maintain a three-way contrast of Mary, merry and marry, whereas many speakers of General American suspend the usual contrast of /eI/, /ε/ and , as established by minimal triplets like sail, sell and Sal or pain, pen and pan, in this environment, making Mary, merry and marry homophones. Although the vowel found here often sounds like [ε], this cannot be regarded as a normal realization of /ε/, since /ε/ is a phoneme which contrasts with /eI/ and

, as established by minimal triplets like sail, sell and Sal or pain, pen and pan, in this environment, making Mary, merry and marry homophones. Although the vowel found here often sounds like [ε], this cannot be regarded as a normal realization of /ε/, since /ε/ is a phoneme which contrasts with /eI/ and , and that contrast is not possible here. So, we can set up an archiphoneme /E/ in just those cases before /r/, again signaling that a contrast otherwise found in all environments fails to manifest itself here.

, and that contrast is not possible here. So, we can set up an archiphoneme /E/ in just those cases before /r/, again signaling that a contrast otherwise found in all environments fails to manifest itself here.

|

|

|

|

دخلت غرفة فنسيت ماذا تريد من داخلها.. خبير يفسر الحالة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ثورة طبية.. ابتكار أصغر جهاز لتنظيم ضربات القلب في العالم

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

سماحة السيد الصافي يؤكد ضرورة تعريف المجتمعات بأهمية مبادئ أهل البيت (عليهم السلام) في إيجاد حلول للمشاكل الاجتماعية

|

|

|