تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Universal gravitation

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 7

2024-02-04

1031

What else can we understand when we understand gravity? Everyone knows the earth is round. Why is the earth round? That is easy; it is due to gravitation. The earth can be understood to be round merely because everything attracts everything else and so it has attracted itself together as far as it can! If we go even further, the earth is not exactly a sphere because it is rotating, and this brings in centrifugal effects which tend to oppose gravity near the equator. It turns out that the earth should be elliptical, and we even get the right shape for the ellipse. We can thus deduce that the sun, the moon, and the earth should be (nearly) spheres, just from the law of gravitation.

What else can you do with the law of gravitation? If we look at the moons of Jupiter, we can understand everything about the way they move around that planet. Incidentally, there was once a certain difficulty with the moons of Jupiter that is worth remarking on. These satellites were studied very carefully by Rømer, who noticed that the moons sometimes seemed to be ahead of schedule, and sometimes behind. (One can find their schedules by waiting a very long time and finding out how long it takes on the average for the moons to go around.) Now they were ahead when Jupiter was particularly close to the earth and they were behind when Jupiter was farther from the earth. This would have been a very difficult thing to explain according to the law of gravitation—it would have been, in fact, the death of this wonderful theory if there were no other explanation. If a law does not work even in one place where it ought to, it is just wrong. But the reason for this discrepancy was very simple and beautiful: it takes a little while to see the moons of Jupiter because of the time it takes light to travel from Jupiter to the earth. When Jupiter is closer to the earth the time is a little less, and when it is farther from the earth, the time is more. This is why moons appear to be, on the average, a little ahead or a little behind, depending on whether they are closer to or farther from the earth. This phenomenon showed that light does not travel instantaneously, and furnished the first estimate of the speed of light. This was done in 1676.

If all of the planets pull on each other, the force which controls, let us say, Jupiter in going around the sun is not just the force from the sun; there is also a pull from, say, Saturn. This force is not really strong, since the sun is much more massive than Saturn, but there is some pull, so the orbit of Jupiter should not be a perfect ellipse, and it is not; it is slightly off, and “wobbles” around the correct elliptical orbit. Such a motion is a little more complicated. Attempts were made to analyze the motions of Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus on the basis of the law of gravitation. The effects of each of these planets on each other were calculated to see whether or not the tiny deviations and irregularities in these motions could be completely understood from this one law. Lo and behold, for Jupiter and Saturn, all was well, but Uranus was “weird.” It behaved in a very peculiar manner. It was not travelling in an exact ellipse, but that was understandable, because of the attractions of Jupiter and Saturn. But even if allowance were made for these attractions, Uranus still was not going right, so the laws of gravitation were in danger of being overturned, a possibility that could not be ruled out. Two men, Adams and Le Verrier, in England and France, independently, arrived at another possibility: perhaps there is another planet, dark and invisible, which men had not seen. This planet, N, could pull on Uranus. They calculated where such a planet would have to be in order to cause the observed perturbations. They sent messages to the respective observatories, saying, “Gentlemen, point your telescope to such and such a place, and you will see a new planet.” It often depends on with whom you are working as to whether they pay any attention to you or not. They did pay attention to Le Verrier; they looked, and there planet N was! The other observatory then also looked very quickly in the next few days and saw it too.

Fig. 7–6. A double-star system.

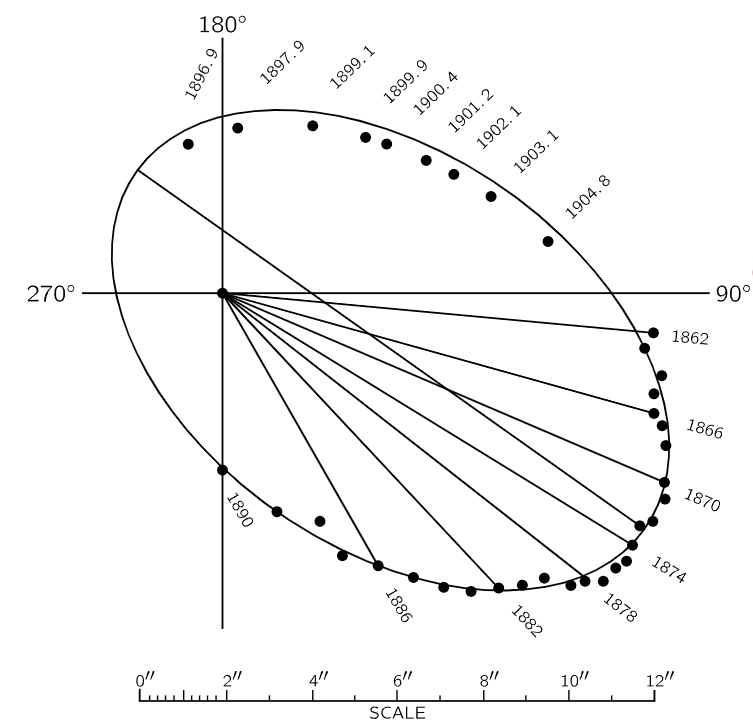

Fig. 7–7. Orbit of Sirius B with respect to Sirius A.

This discovery shows that Newton’s laws are absolutely right in the solar system; but do they extend beyond the relatively small distances of the nearest planets? The first test lies in the question, do stars attract each other as well as planets? We have definite evidence that they do in the double stars. Figure 7–6 shows a double star—two stars very close together (there is also a third star in the picture so that we will know that the photograph was not turned). The stars are also shown as they appeared several years later. We see that, relative to the “fixed” star, the axis of the pair has rotated, i.e., the two stars are going around each other. Do they rotate according to Newton’s laws? Careful measurements of the relative positions of one such double star system are shown in Fig. 7–7. There we see a beautiful ellipse, the measures starting in 1862 and going all the way around to 1904 (by now it must have gone around once more). Everything coincides with Newton’s laws, except that the star Sirius A is not at the focus. Why should that be? Because the plane of the ellipse is not in the “plane of the sky.” We are not looking at right angles to the orbit plane, and when an ellipse is viewed at a tilt, it remains an ellipse but the focus is no longer at the same place. Thus, we can analyze double stars, moving about each other, according to the requirements of the gravitational law.

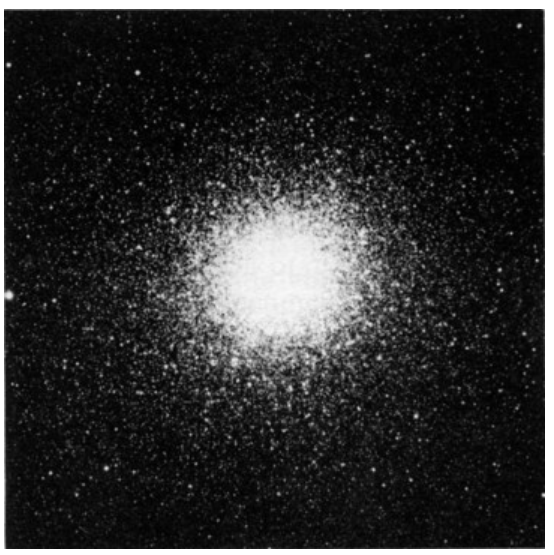

Fig. 7–8. A globular star clusters.

That the law of gravitation is true at even bigger distances is indicated in Fig. 7–8. If one cannot see gravitation acting here, he has no soul. This figure shows one of the most beautiful things in the sky—a globular star cluster. All of the dots are stars. Although they look as if they are packed solid toward the center, that is due to the fallibility of our instruments. Actually, the distances between even the centermost stars are very great and they very rarely collide. There are more stars in the interior than farther out, and as we move outward there are fewer and fewer. It is obvious that there is an attraction among these stars. It is clear that gravitation exists at these enormous dimensions, perhaps 100,000 times the size of the solar system. Let us now go further, and look at an entire galaxy, shown in Fig. 7–9. The shape of this galaxy indicates an obvious tendency for its matter to agglomerate. Of course, we cannot prove that the law here is precisely inverse square, only that there is still an attraction, at this enormous dimension, that holds the whole thing together. One may say, “Well, that is all very clever but why is it not just a ball?” Because it is spinning and has angular momentum which it cannot give up as it contracts; it must contract mostly in a plane. (Incidentally, if you are looking for a good problem, the exact details of how the arms are formed and what determines the shapes of these galaxies has not been worked out.) It is, however, clear that the shape of the galaxy is due to gravitation even though the complexities of its structure have not yet allowed us to analyze it completely. In a galaxy we have a scale of perhaps 50,000 to 100,000 light years. The earth’s distance from the sun is 8 1/3 light minutes, so you can see how large these dimensions are.

Fig. 7–9. A galaxy (M81).

Fig. 7–10. A cluster of galaxies.

Gravity appears to exist at even bigger dimensions, as indicated by Fig. 7–10, which shows many “little” things clustered together. This is a cluster of galaxies, just like a star cluster. Thus, galaxies attract each other at such distances that they too are agglomerated into clusters. Perhaps gravitation exists even over distances of tens of millions of light years; so far as we now know, gravity seems to go out forever inversely as the square of the distance.

Fig. 7–11. An interstellar dust cloud.

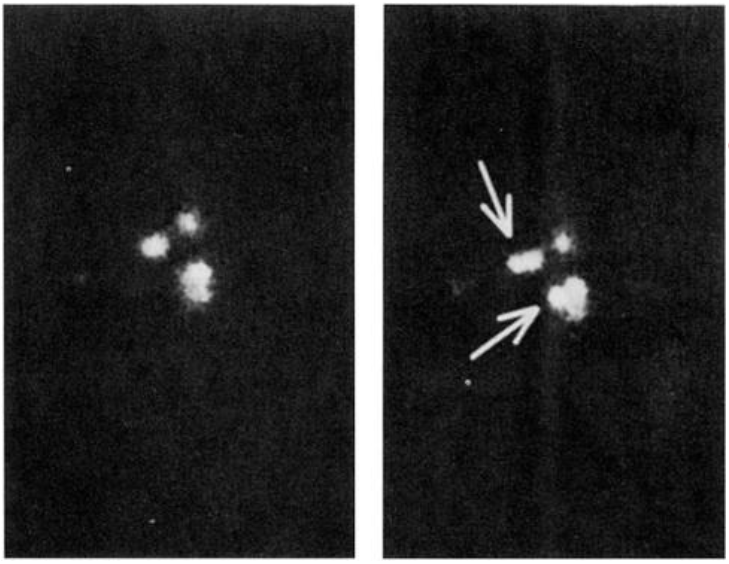

Not only can we understand the nebulae, but from the law of gravitation we can even get some ideas about the origin of the stars. If we have a big cloud of dust and gas, as indicated in Fig. 7–11, the gravitational attractions of the pieces of dust for one another might make them form little lumps. Barely visible in the figure are “little” black spots which may be the beginning of the accumulations of dust and gases which, due to their gravitation, begin to form stars. Whether we have ever seen a star form or not is still debatable. Figure 7–12 shows the one piece of evidence which suggests that we have. At the left is a picture of a region of gas with some stars in it taken in 1947, and at the right is another picture, taken only 7 years later, which shows two new bright spots. Has gas accumulated, has gravity acted hard enough and collected it into a ball big enough that the stellar nuclear reaction starts in the interior and turns it into a star? Perhaps, and perhaps not. It is unreasonable that in only seven years we should be so lucky as to see a star change itself into visible form; it is much less probable that we should see two!

Fig. 7–12. The formation of new stars?