تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

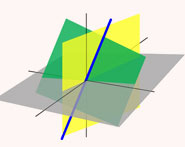

الهندسة

الهندسة

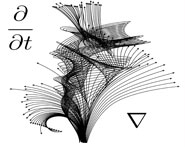

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 25-3-2017

Date: 21-3-2017

Date: 17-3-2017

|

Died: 9 April 1951 in Oslo, Norway

Vilhelm Bjerknes was a son of Carl Bjerknes and Aletta Koren, whose father was a minister in the Church in West Norway. See the biography of Carl Bjerknes for more details of his family background. Carl, Vilhelm's father, was not a good experimentalist and so while he was a young boy Vilhelm did much work assisting his father in carrying out experiments to verify the theoretical predictions which came out of his father's hydrodynamic research. Vilhelm began this work with his father when he was still quite a young boy and he continued the collaboration after he began his undergraduate studies at the University of Kristiania in 1880. Vilhelm wrote his first paper New hydrodynamic investigations in 1882 when he was only 20 years old.

We should note that the different spelling of Christiania or Kristiania is not an error. The city was named Christiania when Vilhelm was born there, became Kristiania in 1877, then was renamed Oslo in 1925. Throughout Vilhelm Bjerknes's life he was associated with this city with its three different names and all three names appear in this biography.

In 1888 Vilhelm was awarded his Master's Degree from the University of Kristiania after studying mathematics and physics. During his final years of study at university Bjerknes decided that he would have to end the collaboration with his father. By this time Carl Bjerknes had become a recluse and continuing the collaboration would have led, Vilhelm believed, to his own scientific isolation. It must have been a painful decision for young Vilhelm, who was devoted to his father, but he feared falling into the pattern of work that his father had developed, leaving him outside the mainstream of science. It was a mature decision for the young man who clearly saw that he had a major role to play in the future of scientific research.

After graduating from Kristiania, Bjerknes was awarded a state scholarship which allowed him to study abroad. He later wrote (thinking about both himself and his father) that:-

... foreign scientific travels [were] indispensable for anyone in our restricted situation who wishes to develop into a man of science.

He went to Paris in 1889 where he attended Poincaré's lectures on electrodynamics, then he went to Bonn as Hertz's assistant. This was not a short trip, for Bjerknes spent two years from 1890 to 1892 in Bonn. Together Hertz and Bjerknes studied electrical resonance which proved important in the development of radio. Bjerknes remained a close friend of Hertz and his family from that time on. He returned to Norway to complete his doctoral thesis on work he had undertaken in Bonn. The doctorate was awarded in 1892 when he was thrity years old.

Bjerknes was appointed as a lecturer at the Högskola (School of Engineering) in Stockholm in 1893 then, two years later, he became professor of applied mechanics and mathematical physics at the University of Stockholm. He continued developing his father's ideas but also making other significant advances, generalising results of Thomson and Helmholtz. Important for the future direction of Bjerknes's research was the fact that he now applied the generalisation of the theory of vortices of Thomson and Helmholtz, which he had studied, to motions in the atmosphere and the ocean. Bjerknes began to work out a research plan that he would use hydrodynamics and thermodynamics so that, given a particular state of the atmosphere, he would be able to compute its future state.

In 1893 he married S H Bonnevie who came from a Huguenot family which had fled from France to Norway at the time of persecution. She was a student of natural sciences at the University of Christiania. Gold writes [6]:-

Her warm hearted and gracious hospitality contributed in no small degree to the happy social atmosphere of the meteorological community at Bergen ...

They had four sons. Their son, Jacob Bjerknes, was born on 2 November 1897. Jacob would later collaborate with his father and become a famous meteorologist in his own right, discovering the mechanism which controls the behaviour of cyclones.

In 1905 Vilhelm Bjerknes visited the United States, described some of the fundamental steps he had already taken in the theory of air masses, and explained his plans to apply mathematics to weather forecasting. The Carnegie Foundation were impressed and they awarded him funds to pursue this research. He was to continue to receive this grant from the Carnegie Foundation for 36 years.

Bjerknes accepted the chair of applied mechanics and mathematical physics at the University of Kristiania in 1907. He was a very different person from his father in that he gathered a large group of collaborators round him wherever he went. He built up a large school in Kristiania studying dynamic meteorology.

In 1912 Bjerknes was offered the chair of geophysics at the University of Leipzig, and also the directorship of the new Leipzig Geophysical Institute which was just being founded. He accepted the positions taking some of his collaborators from Kristiania with him. Soon he was joined by other members of the Kristiania team, and by his son Jacob Bjerknes who also became a collaborator during his time in Leipzig. Jacob and Vilhelm Bjerknes collaborated in establishing a network of weather stations in Norway and it was data gathered from these weather stations which led to their theory of polar fronts.

In 1917 Bjerknes was offered a chair at the University of Bergen and he was given the opportunity to found the Bergen Geophysical Institute. At first he was rather reluctant to leave Leipzig since he feared for the long-term future of the Geophysical Institute there but, once convinced that the work of the Institute would continue, he accepted the Bergen offer. Despite being 55 years old when he moved to Bergen, most historians agree that Bjerknes did his best work there. This work on a mathematical approach to weather forecasting is described in [2]:-

Efforts at incorporating numerical data on weather into mathematical formulas that could then be used for forecasting were initiated early in the century at the Norwegian Geophysical Institute. Vilhelm Bjerknes and his associates at Bergen succeeded in devising equations relating the measurable components of weather, but their complexity precluded the rapid solutions needed for forecasting. Out of their efforts, however, came the polar front theory for the origin of cyclones and the now-familiar names of cold front, warm front, and stationary front for the leading edges of air masses ...

The next step forward in the mathematical approach was due to Richardson in 1922 when he reduced the complicated equations produced by Bjerknes's Bergen School to long series of simple arithmetic operations. However, until the advent of computers, these were still impossible to solve in the time-scale required for weather forecasting.

Most of Bjerknes's major results in this area appear in On the Dynamics of the Circular Vortex with Applications to the Atmosphere and to Atmospheric Vortex and Wave Motion (1921) [1]:-

One of his finest books, it contains a clear explanation of the most important basic ideas in his research.

There were two scientists from whom Bjerknes had the greatest admiration. One was Heaviside and the other was Hertz. Bjerknes had visited Heaviside in 1919 in Torquay, England. By that time Heaviside was living a lonely life in hard financial circumstances and Bjerknes did his best to assist him. In a letter to Heaviside in 1922 Bjerknes wrote [6]:-

It is not unlikely that I shall write something presently of my old master Hertz in whose laboratory I worked in 1890-91. I am one of his very few personal pupils. this makes it a duty for me to bring some recollections of him. I have always considered him and you as the two real inheritors of Maxwell and I am very glad that I have had the good luck to come into personal contact with these two only ones.

In 1923 Bjerknes published a collection of papers on electrical resonance, and wrote an introduction dedicating them to the memory of Hertz.

Bjerknes made his final move in 1926 when he accepted the chair of applied mechanics and mathematical physics at the University of Oslo (Kristiania had been renamed Oslo in 1925). His work certainly was not confined to the mathematics of weather forecasting for he continued to study the hydrodynamical work started by his father. He also produced the theory, in 1926, that sun spots are the erupting ends of magnetic vortices broken by the sun's differential rotation.

During his years at the University of Oslo until his retirement in 1932 Bjerknes put a considerable effort into teaching. He published a book on vector analysis in 1929 which was designed as the first of a larger textbook on theoretical physics. It was a project which he never completed but [3]:-

... his alert mind was not dimmed by age, and he went on working long after his retirement.

In 1928 Bjerknes' wife died and at that time her sister, Professor Kristine Bonnevie, became his housekeeper.

As indicated in the above quote, Bjerknes remained active after his retirement. In particular he became President of the Association of Meteorology of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics in 1932. He organised the International Meeting of the Association in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1936. He addressed the Silver Jubilee celebrations of the Leipzig Geophysical Institute in 1938, encouraging them to work harder on the problems of weather forecasting.

In the following year World War II broke out [6]:-

The outbreak of the war in 1939 was a sore blow to Bjerknes, imbued as he was with ideals of international friendship and cooperation and with his many ties with Germany and German scientific life. During the occupation of Norway he showed towards the invaders a dignified and courageous severity.

Although Bjerknes was 84 years old in 1946, he made the trip to the Newton Tercentenery Celebrations in England.

Gold writes of his character [6]:-

Bjerknes was dignified in manner, in appearance and in his presentation of his scientific work, but with his dignity he combined a certain modesty and an enthusiasm which both attracted and stimulated younger men.

T Bergeron, one of his students, added:-

The fine sense of humour which [Bjerknes] possessed, together with his genius, his far-sightedness, increased during a long and migrating career, made him a very human individual. But he was certainly a little shy or repressed.

More than once I heard him state that he never learned easily, that he lacked the natural ability for easily communicating his thoughts verbally or in writing, that he had to be a hard worker - and certainly he was one.

The honours which Bjerknes was awarded are far too numerous to list here, but we mention a few. He was elected to many national academies such as the Norwegian Academy of Oslo (1893), the Washington Academy of Science (1906), the Dutch Academy of Science (1923), the Prussian Academy (1928), the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1930), the Royal Society of London (1933), the U.S. National Academy of Science (1934), and the Pontifical Academy of Rome(1936).

He also received honorary degrees from many universities such as the University of St Andrews (1926) and the University of Copenhagen (1929). Among the Medal he received were the Agassiz Medal for Oceanography (1926), the Symons Medal for Meteorology (1932), and the Buy-Ballot Medal for Meteorology (1933).

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

دخلت غرفة فنسيت ماذا تريد من داخلها.. خبير يفسر الحالة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ثورة طبية.. ابتكار أصغر جهاز لتنظيم ضربات القلب في العالم

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

سماحة السيد الصافي يؤكد ضرورة تعريف المجتمعات بأهمية مبادئ أهل البيت (عليهم السلام) في إيجاد حلول للمشاكل الاجتماعية

|

|

|