النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية|

Read More

Date: 13-3-2016

Date: 15-3-2016

Date: 7-3-2016

|

Laboratory Diagnosis

Introduction

Infections can be diagnosed either directly by detection of the pathogen or components thereof or indirectly by antibody detection methods. The reliability of laboratory results is characterized by the terms sensitivity and specificity, their value is measured in terms of positive to negative predictive value. These predictive values depend to a great extent on prevalence. In direct laboratory diagnosis, correct material sampling and adequate transport precautions are an absolute necessity. The classic methods of direct laboratory diagnosis include microscopy and culturing. Identification of pathogens is based on morphological, physiological, and chemical characteristics. Among the latter, the importance of detection of pathogen-specific nucleotide sequences is constantly increasing. Development of sensitive test systems has made direct detection of pathogen components in test materials possible in some cases. The molecular biological methods used are applied with or without amplification of the sequence sought as the case warrants. Direct detection can also employ polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies to detect and identify antigens.`

Preconditions, General Methods, Evaluation

Preconditions

The field of medical microbiology dealing with laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases is known as diagnostic or clinical microbiology. Modern medical practice, and in particular hospital-based practice, is inconceivable without the cooperation of a special microbiological laboratory.

To ensure optimum patient benefit, the physician in charge of treatment and the laboratory staff must cooperate closely and efficiently. The preconditions include a basic knowledge of pathophysiology and clinical infectiology on the part of the laboratory staff and familiarity with the laboratory work on the part of the treating physician. The following sections provide a brief run-down on what physicians need to know about laboratory procedures.

General Methods and Evaluation

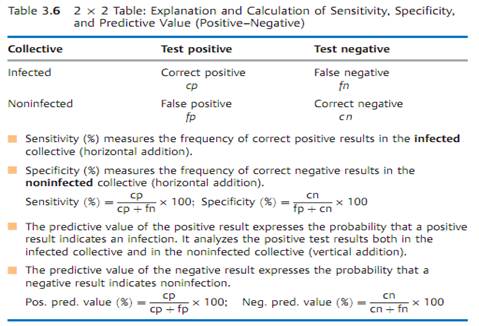

An infectious disease can be diagnosed directly by finding the causal pathogen or its components or products. It can also be diagnosed indirectly by means of antibody detection . The accuracy and value of each of the available diagnostic methods are characterized in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and positive or negative predictive value. These parameters are best understood by reference to a 2 x 2 table (Table 3.6).

By inserting fictitious numbers into the 2 x 2 table, it readily becomes apparent that a positive predictive value will fall rapidly, despite high levels of specificity and sensitivity, if the prevalence level is low (Baye's theorem).

Sampling and Transport of Test Material

It is very important that the material to be tested be correctly obtained (sampled) and transported. In general, material from which the pathogen is to be isolated should be sampled as early as possible before chemotherapy is begun. Transport to the laboratory must be carried out in special containers provided by the institutes involved, usually containing transport mediums— either enrichment mediums (e.g., blood culture bottle), selective growth mediums or simple transport mediums without nutrients. An invoice must be attached to the material containing the information required for processing (using the form provided).

Material from the respiratory tract:

- Swab smear from tonsils.

- Sinus flushing fluid.

- Pulmonary secretion. Expectorated sputum is usually contaminated with saliva and the flora of the oropharynx. Since these contaminations include pathogens that may cause infections of the lower respiratory tract organs, the value of positive findings would be limited. The material can be considered unsuitable for diagnostic testing if more than 25 oral epithelia are present per viewing frame at 100 x magnification. Morning sputum from flushing the mouth or after induction will result in suitable samples. Sputum is not analyzed for anaerobes.

- Useful alternatives to expectorated sputum include bronchoscopically sampled bronchial secretion, flushing fluid from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), transtracheal aspirate or a pulmonary puncture biopsy. These types of material are required if an anaerobe infection is suspected. The material must then be transported in special anaerobe transport containers.

Material from the urogenital tract:

- Urine. Midstream urine is in most cases contaminated with the flora of the anterior urethra, which often corresponds to the pathogen spectrum of urinary tract infections. Bacterial counts must be determined if “contamination” is to be effectively differentiated from “infection.” At counts in morning urine of -105/ml an infection is highly probable, at counts of -103 rather improbable. At counts of around 104/ml the test should be repeated. Lower counts may also be diagnostically significant in urethrocystitis. The dipstick method, which can be used in any medical practice, is a simple way of estimating the bacterial count: a stick coated with nutrient medium is immersed in the midstream urine, then incubated. The colony count is then estimated by comparing the result with standardized images.

- Catheterizing the urinary bladder solely for diagnostic purposes is inadvisable due to the potential for iatrogenic infection. Uncontaminated bladder urine is obtainable only by means of a suprapubic bladder puncture.

- Genital secretions are sampled with smear swabs and must be transported in special transport mediums.

Blood:

- For a blood culture, at least 10-20 ml of venous blood should be drawn sterilely into one aerobic and one anaerobic blood culture bottle. Sample three times a day at intervals of several hours (minimum interval one hour).

- For serology, (2-)5 ml of native blood will usually suffice. Take the initial sample as early as possible and a second one 1-3 weeks later to register any change in the antibody titer.

Pus and wound secretions:

- For surface wounds sample material with smear swabs and transport in preservative transport mediums. Such material is only analyzed for aerobic bacteria.

- For deep and closed wounds, liquid material (e.g., pus) should be sampled, if possible, with a syringe. Use special transport mediums for anaerobes.

Material from the gastrointestinal tract:

- Use a small spatula to place a portion of stool about the size of a cherry in liquid transport medium for shipment.

- Transport duodenal juice and bile in sterile tubes. Use special containers if anaerobes are suspected.

Cerebrospinal fluid, puncture biopsies, exudates, transudates:

- Ensure sampling sterility. Use special containers if anaerobes are suspected.

Microscopy

Bacteria are so small that a magnification of 1000 x is required to view them properly, which is at the limit of light microscope capability. At this magnification, bacteria can only be discerned in a preparation in which their density is at least 104-105 bacteria per ml.

Microscopic examination of such material requires a slide preparation:

- Native preparations, with or without vital staining, are used to observe living bacteria. The poor contrast of such preparations makes it necessary to amplify this aspect (dark field and phase contrast microscopy). Native preparations include the coverslip and suspended drop types.

- Stained preparations are richer in contrast so that bacteria are readily recognized in an illuminated field at 1000 x. The staining procedure kills the bacteria. The material is first applied to a slide in a thin layer, dried in the air, and fixed with heat or methyl alcohol. Simple and differential staining techniques are used. The best-known simple staining technique employs methylene blue. Gram staining is the most important differential technique (Table 3.7): Gram-positive bacteria stain blue-violet, Gram-negative bacteria stain red. The Gram-positive cell wall prevents alcohol elution of the stain- iodine complex. In old cultures in which autolytic enzymes have begun to break down the cell walls, Gram-positive cells may test Gram-negative (“Gram-labile” bacteria).

Another differential stain is the Ziehl-Neelsen technique. It is used to stain mycobacteria, which do not “take” gram or methylene blue stains due to the amounts of lipids in their cell walls. Since mycobacteria cannot be destained with HCl-alcohol, they are called acid-resistant rods. The mycobacteria are stained red and everything else blue.

- Fluorescence microscopy is another special technique. A fluorochrome absorbs shortwave light and emits light with a longer wavelength. Preparations stained with fluorochromes are exposed to light at the required wavelength. The stained particles appear clearly against a dark background in the color of the emitted light. This technique requires special equipment. Its practical application is in the observation of mycobacteria. In immunofluorescence detection, a fluorochrome (e.g., fluorescein isothiocyanate) is coupled to an antibody to reveal the presence of antigens on particle surfaces.

Culturing Methods

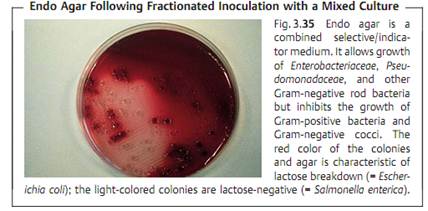

Types of nutrient mediums. Culturing is required in most cases to detect and identify bacteria. Almost all human pathogen bacteria can be cultivated on nutrient mediums. Nutrient mediums are either liquid (nutrient broth) or gelatinous (nutrient agar, containing 1.5-2% of the polysaccharide agarose). Enrichment mediums are complex mediums that encourage the proliferation of many different bacterial species. The most frequently used enrichment medium is the blood agar plate containing 5 % whole blood. Selective mediums allow only certain bacteria to grow and suppress the reproduction of others. Indicator mediums are used to register metabolic processes.

Proliferation forms. Most bacteria show diffuse proliferation in liquid mediums. Some proliferate in “crumbs,” other form a grainy bottom sediment, yet others a biofilm skin at the surface (pseudomonads). Isolated colonies are observed to form on, or in, nutrient agar if the cell density is not too high. These are pure cultures, since each colony arises from a single bacterium or colony-forming unit (CFU). The pure culture technique is the basis of bacteriological culturing methods. The procedure most frequently used to obtain isolated colonies is fractionated inoculation of a nutrient agar plate (Figs. 3.33-3.35).

Use of this technique ensures that isolated colonies will be present in one of the three sectors. Besides obtaining pure cultures, the isolated colony technique has the further advantage of showing the form, appearance, and color of single colonies. The special proliferation forms observed in nutrient broth and nutrient agar give an experienced bacteriologist sufficient information for an initial classification of the pathogen so that identifying reactions can then be tested with some degree of specificity.

Conditions required for growth. The optimum proliferation temperature for most human pathogen bacteria is 37 °C.

Bacteria are generally cultured under atmospheric conditions. It often proves necessary to incubate the cultures in 5% CO2. Obligate anaerobes must be cultured in a milieu with a low redox potential. This can be achieved by adding suitable reduction agents to the nutrient broth or by proliferating the cultures under a gas atmosphere from which most of the oxygen has been removed by physical, chemical, or biological means.

Identification of Bacteria

The essential principle of bacterial identification is to assign an unknown culture to its place within the taxonomic classification system based on as few characteristics as possible and as many as necessary (Table 3.8).

- Morphological characteristics, including staining, are determined under the microscope.

- Physiological characteristics are determined with indicator mediums. Commercially available miniaturized systems are now frequently used for this purpose (Fig. 3.36).

- Chemical characteristics have long been in use to identify bacteria, e.g., in detection of antigen structures. Molecular genetic methods (see below) will play an increasing role in the future.

Molecular Methods

The main objective of the molecular methods of bacterial identification is direct recognition of pathogen-specific nucleotide sequences in the test material. These methods are used in particular in the search for bacteria that are not cultural, are very difficult to culture, or proliferate very slowly. Of course, they can also be used to identify pure bacterial cultures (see above). In principle, any species-specific sequence can be used for identification, but the specific regions of genes coding for 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA are particularly useful in this respect. The following methods are used:

■ DNA probes. Since DNA is made up of two complementary strands of nucleic acids, it is possible to detect single-strand sequences with the hybridization technique using complementary marking of single strands. The probes can be marked with radioactivity (32P, 35S) or nonradioactive reporter molecules (biotin, dioxigenin):

- Solid phase hybridization. The reporter molecule or probe is fixed to a nylon or nitrocellulose membrane (colony blot technique, dot blot technique).

- Liquid phase hybridization. The reporter molecule and probe are in a solute state.

- In-situ hybridization. Detection of bacterial DNA in infected tissue.

■ Amplification. The main objective here is to increase the sensitivity level so as to find the “needle in a haystack.” A number of techniques have been developed to date, which can be classified in three groups:

- Amplification of the target sequence. The oldest and most important among the techniques in this group is the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which is described on p. 409f.). With “real time PCR,” a variant of PCR, the analysis can be completed in 10 minutes.

- Probe amplification.

- Signal amplification.

Direct Detection of Bacterial Antigens

Antigens specific for particular species or genera can be detected directly by means of polyclonal or (better yet) monoclonal antibodies present in the test material. This allows for rapid diagnosis. Examples include the detection of bacterial antigens in cerebrospinal fluid in cases of acute purulent meningitis, detection of gonococcal antigens in secretion from the urogenital tract, and detection of group A streptococcal antigen in throat smear material. These direct methods are not, however, as sensitive as the classic culturing methods. Adsorbance, coagglutination, and latex agglutination tests are frequently used in direct detection. In the agglutination methods, the antibodies with the Fc components are fixed either to killed staphylococcal protein A or to latex particles.

Diagnostic Animal Tests

Animal testing is practically a thing of the past in diagnostic bacteriology. Until a few years ago, bacterial toxins (e.g., diphtheria toxin, tetanus toxin, botulinus toxin) were confirmed in animal tests. Today, molecular genetic methods are used to detect the presence of the toxin gene, which process usually involves an amplification step.

Bacteriological Laboratory Safety

Microbiologists doing diagnostic work will of course have to handle potentially pathogenic microorganisms and must observe stringent regulations to avoid risks to themselves and others. Laboratory safety begins with suitable room designs and equipment (negative-pressure lab rooms, safety hoods)

and goes on to include compliance with the basic rules of work in a microbiological laboratory: protective clothing, no eating, drinking, or smoking, mechanical pipetting aids, hand and working surface disinfection (immediately in case of contamination, otherwise following each procedure), proper disposal of contaminated materials, staff health checks, and proper staff training.

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي ينظّم ندوة حوارية حول مفهوم العولمة الرقمية في بابل

|

|

|