تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

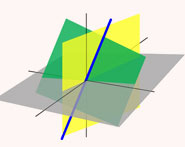

الهندسة

الهندسة

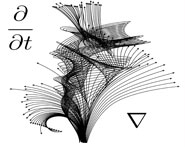

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 23-10-2015

Date: 25-10-2015

Date: 22-10-2015

|

Born: 1350 in Sangamagramma (near Cochin), Kerala, India

Died: 1425 in India

Madhava of Sangamagramma was born near Cochin on the coast in the Kerala state in southwestern India. It is only due to research into Keralese mathematics over the last twenty-five years that the remarkable contributions of Madhava have come to light. In [10] Rajagopal and Rangachari put his achievement into context when they write:-

[Madhava] took the decisive step onwards from the finite procedures of ancient mathematics to treat their limit-passage to infinity, which is the kernel of modern classical analysis.

All the mathematical writings of Madhava have been lost, although some of his texts on astronomy have survived. However his brilliant work in mathematics has been largely discovered by the reports of other Keralese mathematicians such as Nilakantha who lived about 100 years later.

Madhava discovered the series equivalent to the Maclaurin expansions of sin x, cos x, and arctan x around 1400, which is over two hundred years before they were rediscovered in Europe. Details appear in a number of works written by his followers such as Mahajyanayana prakara which means Method ofcomputing the great sines. In fact this work had been claimed by some historians such as Sarma (see for example [2]) to be by Madhava himself but this seems highly unlikely and it is now accepted by most historians to be a 16th century work by a follower of Madhava. This is discussed in detail in [4].

Jyesthadeva wrote Yukti-Bhasa in Malayalam, the regional language of Kerala, around 1550. In [9] Gupta gives a translation of the text and this is also given in [2] and a number of other sources. Jyesthadeva describes Madhava's series as follows:-

The first term is the product of the given sine and radius of the desired arc divided by the cosine of the arc. The succeeding terms are obtained by a process of iteration when the first term is repeatedly multiplied by the square of the sine and divided by the square of the cosine. All the terms are then divided by the odd numbers 1, 3, 5, .... The arc is obtained by adding and subtracting respectively the terms of odd rank and those of even rank. It is laid down that the sine of the arc or that of its complement whichever is the smaller should be taken here as the given sine. Otherwise the terms obtained by this above iteration will not tend to the vanishing magnitude.

This is a remarkable passage describing Madhava's series, but remember that even this passage by Jyesthadeva was written more than 100 years before James Gregory rediscovered this series expansion. Perhaps we should write down in modern symbols exactly what the series is that Madhava has found. The first thing to note is that the Indian meaning for sine of θ would be written in our notation as r sin θ and the Indian cosine of would be r cos θ in our notation, where r is the radius. Thus the series is

r θ = r(r sin θ)/1(r cos θ) - r(r sin θ)3/3r(r cos θ)3 + r(r sin θ)5/5r(r cos θ)5- r(r sin θ)7/7r(r cos θ)7 + ...

putting tan = sin/cos and cancelling r gives

θ = tan θ - (tan3θ)/3 + (tan5θ)/5 - ...

which is equivalent to Gregory's series

tan-1θ = θ - θ3/3 + θ5/5 - ...

Now Madhava put q = π/4 into his series to obtain

π/4 = 1 - 1/3 + 1/5 - ...

and he also put θ = π/6 into his series to obtain

π = √12(1 - 1/(3×3) + 1/(5×32) - 1/(7×33) + ...

We know that Madhava obtained an approximation for π correct to 11 decimal places when he gave

π = 3.14159265359

which can be obtained from the last of Madhava's series above by taking 21 terms. In [5] Gupta gives a translation of the Sanskrit text giving Madhava's approximation of π correct to 11 places.

Perhaps even more impressive is the fact that Madhava gave a remainder term for his series which improved the approximation. He improved the approximation of the series for π/4 by adding a correction term Rn to obtain

π/4 = 1 - 1/3 + 1/5 - ... 1/(2n-1) ± Rn

Madhava gave three forms of Rn which improved the approximation, namely

Rn = 1/(4n) or

Rn = n/(4n2 + 1) or

Rn = (n2 + 1)/(4n3 + 5n).

There has been a lot of work done in trying to reconstruct how Madhava might have found his correction terms. The most convincing is that they come as the first three convergents of a continued fraction which can itself be derived from the standard Indian approximation to π namely 62832/20000.

Madhava also gave a table of almost accurate values of half-sine chords for twenty-four arcs drawn at equal intervals in a quarter of a given circle. It is thought that the way that he found these highly accurate tables was to use the equivalent of the series expansions

sin θ = θ - θ3/3! + θ5/5! - ...

cos θ = 1 - θ2/2! + θ4/4! - ...

Jyesthadeva in Yukti-Bhasa gave an explanation of how Madhava found his series expansions around 1400 which are equivalent to these modern versions rediscovered by Newton around 1676. Historians have claimed that the method used by Madhava amounts to term by term integration.

Rajagopal's claim that Madhava took the decisive step towards modern classical analysis seems very fair given his remarkable achievements. In the same vein Joseph writes in [1]:-

We may consider Madhava to have been the founder of mathematical analysis. Some of his discoveries in this field show him to have possessed extraordinary intuition, making him almost the equal of the more recent intuitive genius Srinivasa Ramanujan, who spent his childhood and youth at Kumbakonam, not far from Madhava's birthplace.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

لخفض ضغط الدم.. دراسة تحدد "تمارين مهمة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

طال انتظارها.. ميزة جديدة من "واتساب" تعزز الخصوصية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مشاتل الكفيل تزيّن مجمّع أبي الفضل العبّاس (عليه السلام) بالورد استعدادًا لحفل التخرج المركزي

|

|

|