Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 5-3-2022

Date: 2023-12-11

Date: 5-3-2022

|

Meet the family

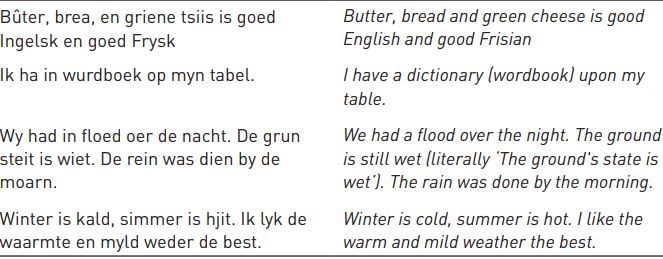

From the language family tree, it can be seen that English is ‘genetically’ (the use of this biological metaphor is common in describing the relationships between languages) part of the West Germanic branch, and that its closest relative is Frisian, a language spoken in the north-west Netherlands, which has recognized minority language status and its own language academy (Fryske Akademy, founded in 1938). The close family relationship between the two languages should not be taken too literally: they have diverged from each other considerably and have had very different contact histories. English vocabulary was hugely influenced by Norman French as a result of the Norman conquest of 1066, while the Frisian language has seen extensive lexical borrowing from Dutch. But nonetheless, close similarities to English are still evident in the following examples, taken from the Virtual Linguist website:

The practitioners of comparative linguistics in the nineteenth century recognized that if their discipline were to be taken seriously as a science, it required testable laws and hypotheses akin to those of geology or physics. The Junggrammatiker or Neogrammarian hypothesis, which emerged in the last quarter of the century, was very much a response to the perceived need for scientific rigour. The hypothesis held that changes to a particular sound in a particular environment simultaneously affect all cases where that environmental condition is satisfied. Sound laws were held to be exceptionless, unless such exceptions could be explained either by other laws (Verner’s Law, for example, explained a number of apparent exceptions to Grimm’s Law) or by analogy. The best-known formulation of the hypothesis is found in Osthoff and Brugmann’s Foundations of Language, published in 1878.

This position statement in what some have called the Neogrammarian ‘manifesto’ has been often criticized, not always fairly. Evidence from Gilliéron’s monumental Atlas Linguistique de la France, painstakingly compiled in the last decade of the nineteenth century, seemed to belie the neat, exceptionless laws of the Neogrammarians, and led the author to conclude that ‘every word has its own history’. But the differences between these apparently opposed positions were essentially ones of emphasis: it is possible to observe the general regularities of patterns of sound change while acknowledging (as the caveats in the above quotation clearly attempt to do) the specific circumstances of individual lexical items which may not have followed the general pattern.

Where the neogrammarians emphasized historical regularity, dialectologists stressed the micro-etymologies of individual items. Both, however, focused on changes which had already happened: not until the advent of variationist sociolinguistics in the 1960s would change in progress be observed, and found in some cases to be lexically diffused, i.e. affecting some sets of words before others, and in others to be influenced by sociological, psychological or aesthetic factors, adopted at different rates by different groups.

|

|

|

|

4 أسباب تجعلك تضيف الزنجبيل إلى طعامك.. تعرف عليها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أكبر محطة للطاقة الكهرومائية في بريطانيا تستعد للانطلاق

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تبحث مع العتبة الحسينية المقدسة التنسيق المشترك لإقامة حفل تخرج طلبة الجامعات

|

|

|