Spelling and speech

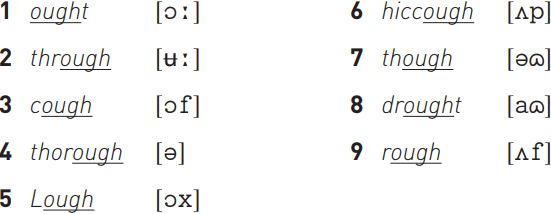

The relationship between spelling and speech can be ridiculously idiosyncratic, as seen in this example from English:

All nine words contain the same orthographical sequence ough: in every case its pronunciation (indicated in International Phonetic Alphabet, or IPA, symbols, which will be explained later) differs, and in no case is the g or h ever pronounced, at least not in standard English. Worse, the variation seems largely arbitrary, so if you’re a non-native speaker attempting to learn English from a book, you'll have little to go on when a new word, say, trough, bough or chough (pronunciations 3, 8 and 9 respectively), comes along. A visiting Martian, informed that the woefully inconsistent soundsymbol relationship demonstrated above forms part of the accepted written convention for the modern world’s most powerful and prestigious language, might reasonably conclude that humans had taken leave of their senses.

French spelling has few of the illogicalities of English (though one might mention in passing the case of aulx – ‘heads of garlic’ – which has four letters, but only one sound ‘o’ [o], which doesn’t appear in the word!). It does, however, have a number of arcane grammatical spelling conventions, which few French citizens ever completely master. A case in point is the preceding direct object agreement rule, which requires past participles to agree in number and gender with a direct object (not an indirect one), but only if it precedes, so J’ai vu la montagne (‘I saw/have seen the mountain’) but Je l’ai vue (‘I saw/have seen it’), with a final e to indicate that the pronoun l’ (elided form of la) is feminine, because it refers to la montagne. The complexity of this rule, which takes up four full pages of the French grammarians’ bible Le Bon Usage (plus a further 12 pages on special cases), is compounded by the fact that in most cases it has no effect on pronunciation.

In his book Talk to the Snail: Ten Commandments for Understanding the French, Steven Clarke bravely attempts to explain to a layperson why J’adore les chaussures que tu m’as offertes (I love the shoes you gave me) requires an agreement in es, and warns his readers:

This observation is true enough, no doubt, for the prescriptive written language, but French people have no more trouble talking to each other than any other nationality does, as anyone who has witnessed heated intellectual debate in a French café can testify.

The above are, admittedly, extreme examples, but everyday inconsistencies in the relationship between speech and writing are not hard to find. The same letter (or grapheme) will often have more than one sound value (think about the pronunciation of c in code and ice) or, conversely, the same vowel or consonant may be represented by different letters or letter combinations (take for example the ‘k’ sounds in cabbage, back, charisma, Iraq, flak, accord, bacchanalia, extent, mosquito, Khmer, biscuit). Little wonder that the sequence ghoti has been facetiously proposed as an alternative spelling of ‘fish’: gh as in rough, o as in women and ti as in nation.

English is far from alone in its poor fit between speech and writing: all languages with alphabetic writing systems present inconsistencies of this kind to a greater or lesser degree. The reason, in a nutshell, is that pronunciation changes too rapidly for spelling to keep up, with the result that writing systems are often a better guide to the way languages used to sound than to the way they are spoken now. The initial k of knave, for example, reflects an earlier state of English in which it was actually pronounced (it still is in its German cognate Knabe, ‘lad’). Other oddities, too, give clues to previous states of the language. The first vowel of mete sounds more like the vowel in ski than that of led because spelling hasn’t yet caught up with changes that occurred during the Great Vowel Shift of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

The seductively linear nature of writing can also engender some false assumptions about speech. We tend, for example, to think of ‘words’ as things separated by convenient orthographical gaps, as they are on a page. The reality, of course, is that in speech, whatwesayisrolledtogetherinsequenceslikethis (only robots in low-budget science fiction movies actually mark a pause between words when they speak). From the spoken language perspective, watertight definitions of ‘words’ prove elusive. Is blackberry, for example, one word or two? What about Jack-in-the-box: one word, or four? Do short, unstressed items like a or the qualify as words at all? When we consider such questions, as we usually do, from the perspective of the written word, they seem quite trivial, but they are important for our understanding of how children break down and make sense of the language data they hear when learning their mother tongue. It’s easy to forget, as adults, that we were at our most successful as language learners when we were infants, and there wasn’t a grammar book, verb conjugation table or dictionary in sight.

For a variety of reasons, then, linguists accord primacy to speech, and work primarily with spoken language data. This will often require speech sounds (rather than letters or graphemes) to be noted down, a task for which, as we’ve seen, conventional orthographies are clearly ill-suited. To address this problem, the IPA, first published in 1888 and regularly updated since, provides a common set of symbols which enables linguists to transcribe the sounds of all languages precisely and consistently (conventionally between square brackets, as for the ough examples above). This demands a strict principle of one-to-one correspondence between sound and symbol: what you see is always exactly what you get and, unlike with conventional spelling, a change in pronunciation necessarily entails a change in transcription. Fortunately, IPA symbols are mostly familiar and easily learned, because they have been largely taken from the Western alphabets with which its founders were most familiar.

When the focus of enquiry is shifted from writing to speech, as linguists argue it must be, many of our common-sense assumptions about language are called into question. For example, most English speakers, if asked the question ‘How many vowels are there in English?’ will probably answer ‘Five: a, e, i, o, u’ (some might add a sixth: y). But this is a statement about the number of vowel letters in the English alphabet, not the number of vowel sounds. In fact, the number of vowel contrasts used by English speakers to distinguish words is considerably higher. Consider, for example, the different pronunciations represented by a alone in cart, cat and Kate, or the eight different vowel sounds rendered by the sequence ough above. In total, there are 21 vowel phonemes, i.e. sounds which are used to contrast words, in Received Pronunciation (RP), the standard British English accent favored by BBC newsreaders, though not all English speakers use all of them: Northern English speakers of English do not contrast put and putt, for example, while Southern speakers do; many British English speakers no longer contrast paw and pore.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة