تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

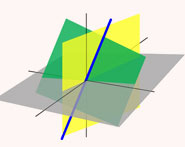

الهندسة

الهندسة

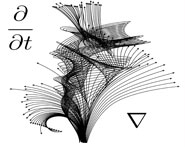

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 29-8-2017

Date: 3-9-2017

Date: 17-8-2017

|

Died: 3 November 1967 in Edinburgh, Scotland

Alec Aitken's family on his father's side were from Scotland, and on his mother's side were from England. Alec's mother, Elizabeth Towers, emigrated with her family to New Zealand from Wolverhampton, England, when she was eight years old. Alexander Aitken, Alec's grandfather on his father's side, had emigrated from Lanarkshire in Scotland to Otago in New Zealand in 1868, and began farming near Dunedin. Alec's father, William Aitken, was one of his fourteen children and William began his working life on his father's farm. However he gave this up and became a grocer in Dunedin. William and Elizabeth had seven children, Alec being the eldest.

He attended the Otago Boys' High School in Dunedin, where he was head boy in 1912, winning a scholarship to Otago University which he entered in 1913. Surprisingly, although he had amazed his school friends and teachers with his incredible memory, he had shown no special mathematical abilities at school. He began to study languages and mathematics at university with the intention of becoming a school teacher but his university career was interrupted by World War I.

In 1915 he enlisted in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force and served in Gallipoli, Egypt, and France, being wounded at the battle of the Somme. His war experiences were to haunt him for the rest of his life. After three months in hospital in Chelsea, London, he was sent back to New Zealand in 1917. The following year he returned to his university studies, graduating in 1920 with First Class Honours in French and Latin but only Second Class Honours in mathematics in which he had no proper instruction. In the year he graduated, Aitken married Mary Winifred Betts who was a botany lecturer at Otago University. They had two children, a girl and a boy.

Aitken followed his original intention and became a school teacher at his old school Otago Boys' High School. His mathematical genius bubbled under the surface and, encouraged by R J T Bell the new professor of mathematics at Otago University, Aitken came to Scotland in 1923 and studied for a Ph.D. at Edinburgh under Whittaker. Aitken's wife, Mary, had continued to lecture at Otago up to the time they left for Edinburgh. His doctoral studies progressed extremely well as he studied an actuHelveticaly motivated problem of fitting a curve to data which was subject to statistical error. Rather remarkably, his Ph.D. thesis was considered so outstanding that he was awarded a D.Sc. for it in 1926. Even before the award of the degree, Aitken was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1925.

He was appointed to Edinburgh University in 1925 where he spent the rest of his life. After holding lecturing posts in actuHelvetica mathematics, then in statistics, then mathematical economics, he became a Reader in statistics in 1936, the year he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Ten years later he was appointed to Whittaker's chair.

Aitken had an incredible memory (he knew π to 2000 places) and could instantly multiply, divide and take roots of large numbers. He describes his own mental processes in the article [4]. Although some may suggest this has little to do with mathematical ability, Aitken himself wrote:-

Familiarity with numbers acquired by innate faculty sharpened by assiduous practice does give insight into the profounder theorems of algebra and analysis.

Aitken's mathematical work was in statistics, numerical analysis, and algebra. In numerical analysis he introduced the idea of accelerating the convergence of a numerical method. He also introduced a method of progressive linear interpolation. In algebra he made contributions to the theory of determinants. He also saw clearly how invariant theory fitted into the theory of groups but wrote that he had never followed through his ideas because of:-

... various circumstances of anxiety, or duty, or bad health ... I have observed my talented younger contemporary Dudley Littlewood's assault and capture most of this terrain.

Aitken wrote several books, one of the most famous being The theory of canonical matrices (1932) which was written jointly with Turnbull. With Rutherford he was editor of a series of the University Mathematical Texts and he himself wrote for the series Determinants and matrices (1939) and Statistical Mathematics (1939). In 1962 he published an article very dear to his heart, namely The case against decimalisation.

In [3], describing his period of recovery from a small operation in 1934 Aitken writes:-

The nights were bad, in the daytime colleagues and other friends visited me, and I tried to think about abstract things, such as the theory of probability and the theory of groups - and I did begin to see more deeply into these rather abstruse disciplines. Indeed I date a change in my interests and an increase in competence, from these weeks of enforced physical inactivity.

Also in [3] Aitken describes the reaction of other mathematicians to his work:-

... the papers on numerical analysis, statistical mathematics and the theory of the symmetric group continued to write themselves in steady succession, with other small notes on odds and ends. Those that I valued most, the algebraic ones, seemed to attract hardly any notice, others, which I regarded as mere application of the highly compressed and powerful notation and algebra of matrices to standard problems in statistics or computation found great publicity in America...

Colin M Campbell, now a colleague of the authors of this archive at the University of St Andrews, was a student in Edinburgh in the early 1960's. He writes:-

Professor Aitken's first year mathematics lectures were rather unusual. The fifty minutes were composed of forty minutes of clear mathematics, five minutes of jokes and stories and five minutes of 'tricks'. For the latter Professor Aitken would ask for members of the class to give him numbers for which he would then write down the reciprocal, the square root, the cube root or other appropriate expression. From the five minutes of 'stories' one also recalls as part of his lectures on probability a rather stern warning about the evils and foolishness of gambling!

In fact Aitken's memory proved a major problem for him throughout his life. For most people memories fade in time which is particularly fortunate for the unpleasant things which happen. However for Aitken memories did not fade and, for example, his horrific memories of the battle of the Somme lived with him as real as the day he lived them. He wrote of them in [2] near the end of his life. These memories must have contributed, or perhaps were the entire cause, of the recurrent ill health he suffered. Collar writes [1]:-

These black periods must have been harrowing in the extreme, but were borne with great fortitude and courage.

The illness eventually led to his death. The book [2], which he wrote to try to put the memories of the Somme behind him, may not have had the desired effect but the book led to Aitken being elected to the Royal Society of Literature in 1964.

Finally we should mention Aitken's love of music. He played the violin and composed music to a very high standard and a professional musician said:-

Aitken is the most accomplished amateur musician I have ever known.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي ينظّم ندوة حوارية حول مفهوم العولمة الرقمية في بابل

|

|

|