تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

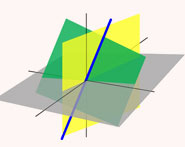

الهندسة

الهندسة

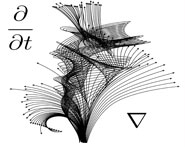

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 3-5-2017

Date: 26-4-2017

Date: 3-5-2017

|

Died: 2 May 1967 in Merriam, Northeast Johnson County, Kansas, USA

Robert Carmichael's parents, Amanda Delight Lessley (1858-1945) and Daniel Monroe Carmichael (1848-1928), were married on 10 January 1878. Amanda was the daughter of Robert Alexander Lessley (whose parents were Irish) and Frances Elizabeth Thompson, while Daniel was the fifth child of Daniel Carmichael (whose father was born in Argyllshire, Scotland) and Margaret Monroe (whose father was also born in Scotland). Robert was the oldest of his parents' ten children.

Carmichael attended Lineville College in Lineville, Clay County, Alabama and graduated with an A.B. in 1898. He married Eula Smith Narramore (1872-1953) from Randolph, Alabama, on 24 November 1901; they had four children, Eunice Annie (born 1902), Erdys Lucile (born 1904), Gershom Narramore (born 1905), and Robert Leslie. Carmichael trained as a Presbyterian Minister and was living in Hartselle, Alabama, in early 1905 when he began submitting problems to the American Mathematical Monthly. He published a large number of problems over the next few years and also began publishing papers. For example, in 1905 and 1906 he published the papers: Six Propositions on Prime Numbers (1905); Note on multiply perfect numbers (1906); Multiply perfect numbers of three different primes (1906); Multiply Perfect Odd Numbers with Three Prime Factors (1906); On the n-Section of an Angle (1906); and Note on the Maximum Indicator of Certain Odd Numbers (1906). He moved to Anniston, Alabama, when he was appointed professor of mathematics at the Presbyterian College for Men at Anniston, Alabama in October 1906.

He taught for three years at the Presbyterian College in Anniston and by 1909 he had around 170 publications in the American Mathematical Monthly, mostly problems and solutions to problems, as well as 13 papers in the Annals of Mathematics and the Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. Leaving Anniston in 1909, he went to Princeton supported by a fellowship. There he undertook research with G D Birkhoff as his thesis advisor and in 1910 he was awarded the prestigious Porter Ogden Jacobus Fellowship, Princeton's highest academic award given to the top ranking graduate student in their final year. He was awarded a Ph.D. in 1911 for his thesis Linear Difference Equations and their Analytic Solutions Linear Difference Equations and their Analytic Solutions.

Following the award of his doctorate, Carmichael was appointed as an Assistant Professor of Mathematics at Indiana University. There he was the thesis advisor to Cora Barbara Hennel who was awarded a Ph.D. by Indiana University for her thesis Transformations and Invariants Connected with Linear Homogeneous Difference Equations and Other Functional Equations in 1912. Carmichael was promoted to Associate Professor at Indiana in 1912 and in the autumn of that year he delivered a short course on the theory of relativity. He published On the Theory of Relativity: Analysis of the Postulates in the Physical Review in September 1912. He begins the article:-

This analysis of the postulates of relativity was undertaken in order to ascertain on just which of the postulates certain fundamental conclusions of the theory depend. A moment's reflection will convince one of the importance of such an analysis. Some of the conclusions of relativity have been attacked by those who admit just the parts of the postulates from which the conclusions objected to can be derived by purely logical processes. In this paper I have sought to establish some of the most fundamental and most readily accessible conclusions of the theory on the smallest possible foundation from the postulates.

In November 1912 he submitted another article On the Theory of Relativity: Philosophical Aspects to the Physical Review which was published in March 1913. His Introduction begins:-

Those who look on physics from the outside not infrequently have the feeling that it has forgotten some of its philosophical foundations. And among physicists themselves this condition of their science has not entirely escaped notice. The physicist who, above all other men, has to deal with space and time has fallen into conventions concerning them of which he is often not aware. It may be true that these conventions are exactly the ones he should make. It is certain, however, that they should be made only by one who is fully conscious of their nature as conventions and not as absolute realities beyond the power of the investigator to modify.

Based on these papers and his lecture course, Carmichael published a 74-page book The theory of relativity in 1913. A review in The Mathematical Gazette states:-

It is now more than eight years since the theory of relativity was expounded by Einstein, and, although the literature of the subject is already considerable, this is practically the first presentation in book form which has been offered to English readers. The author is a mathematician, and has confined his exposition to what may be called the external aspects of the theory ... This simple and logical account will serve a useful purpose by showing what assumptions we are in the habit of making, and wherein these admit of modification without contradicting the evidence of our senses.

Of course this work was on what is now called the special theory of relativity and after Einstein published the general theory of relativity, Carmichael brought out a second edition of his book in 1920. He wrote in the Preface:-

The theory of relativity has now reached its furthest conceivable generalisation in the direction of the covariance of the laws of nature under transformations of coordinates. The older theory of relativity remains valid as a special case of the general theory and may well serve as an introduction to its more far-reaching aspects. Accordingly, in the present (second) edition of this monograph, I have retained the older theory in precisely the same form as in the first edition, ... , and have added ... a compact account of the generalised theory.

Between the publication of the two editions, Carmichael published two further books: The Theory of Numbers (1914) and Diophantine analysis (1915). In a Preface to the first of these he wrote:-

The purpose of this little book is to give the reader a convenient introduction to the theory of numbers, one of the most extensive and most elegant disciplines in the whole body of mathematics. ... this book is made up from material used by me in lectures at Indiana University during the past two years; and the selection of matter, especially of exercises, has been based on the experience gained in this way.

One of these exercises is of particular note. Exercise 8 in Chapter 2 reads:

Show that if the equation φ(x) = n has one solution it always has a second solution, n being given and x being the unknown.

Here φ is Euler's φ-function, so φ(x) is the number of positive integers not greater than x and coprime to x. In fact the 'proof' Carmichael had of this result appeared in the paper On Euler's φ-function that he published in 1907. However, the 'proof' is false as he realised himself and published what had now become a conjecture in Note on Euler's φ-function (1922). In the same paper he showed that any counterexample x had to be greater than 1037. Whether the conjecture is true is still an open question, now known as Carmichael's conjecture, despite considerable efforts being made by many mathematicians. It has been shown, using a computer, that if x is a counterexample to the conjecture, then x > 1010000000; see [6] for details.

Returning to Carmichael's books, in a review of the above mentioned Diophantine analysis, Derrick Norman Lehmer writes:-

The book will serve a valuable end in stimulating interest in this delightful branch of mathematics. There are many interesting and suggestive problems at the end of each chapter, some of which are excellent material for further research.

In 1915 Carmichael left Indiana University. He taught at the University of Chicago Summer School in 1915, then took up an appointment as an Assistant Professor of Mathematics at the University of Illinois in the autumn of that year. He already appears in that role on the title page of Diophantine analysis (1915). He was promoted to Associate Professor of Mathematics in 1918 and to full Professor in 1920. He served as Head of Department from 1929 to 1934, and as acting Dean of the Graduate School in 1933-34. He was elected Dean of the Graduate School in 1934 and served in this role until he retired in 1947 when he was named Dean Emeritus.

We have already mentioned several of the outstanding books written by Carmichael. Let us now look briefly at some of the books he published later in his career. In May 1926 a debate on the theory of relativity was held at Indiana University and Carmichael both participated in the debate and edited the resulting volume A Debate on the Theory of Relativity (1927). In his opening address at the debate Carmichael said that a theory:-

... must be in suitable agreement with the facts of nature, it must have those aesthetic qualities which render it pleasing to the human spirit, and it must furnish what is to us the most agreeable theory from the point of view of convenience.

Also in 1927, in collaboration with James Henry Weaver (1883-1942), Carmichael published The Calculus. A revised edition, with Lincoln La Paz as an additional author, was published in 1937. In 1930 Carmichael, in collaboration with Edwin R Smith, published Plane and Spherical Trigonometry based on lectures the authors had given. They begin the Preface with the words:-

There is very little room for novelty in preparing a textbook for an introductory course in trigonometry. The material and methods are fairly well standardised.

Also in 1930, Carmichael published The Logic of Discovery. Fred Perkins writes [5]:-

The book is written in a very readable style and is heartily recommended to anyone who is anxious to become familiar with the interrelations of mathematics, the physical and social sciences, and philosophy.

Reviewing the same work, H T Davis writes [2]:-

Only at rare intervals does there appear a book devoted to the discussion of problems in epistemology which is thoroughly lucid. At one place or another undefinables are introduced into the discussion and the meaning is then lost in a confusion of words. The book under review therefore is especially noteworthy in the fact that it belongs to that limited class of philosophical essays which defines its terms, states its postulates, and then proceeds to the development of its theme with an inevitable logic. A reader is thus privileged to disagree with the conclusions, not from any feeling of insecurity derived from semantic uncertainties, but only from unwillingness to grant the initial premises. One thus derives unusual satisfaction in the perusal of Professor Carmichael's book since one is never on a single page uncertain as to the meaning of the author.

In 1931 Mathematical Tables and Formulas, compiled by Carmichael and Edwin Smith, appeared. It contains five-place tables of logarithms of numbers, of logarithms of trigonometric functions, and of natural functions. Finally, let us mention another outstanding text by Carmichael Introduction to the Theory of Groups of Finite Order. In it he aimed to give:-

... an exposition which first of all prepares [the reader] for the development of the theory and then rapidly introduces him to a few fundamental theorems by which the construction of a large part of the theory may be effected.

L W Griffiths writes in a review [3]:-

The outstanding merit of the book, in the reviewer's opinion, is the presentation, with great clarity and in less than one hundred pages, of the five fundamental theorems on finite groups and the fundamental results on isomorphism of finite groups.

The reader of this biography may have heard of Carmichael only because of the Carmichael numbers, and have wondered why they have not yet been mentioned. We have left them until now to, in some sense, give them pride of place. Fermat had proved that if n is prime then xn-1 = 1 mod n for every x coprime ton. A 'Carmichael number' is a non-prime n satisfying this condition for any x coprime to n. It was given this name since Carmichael discovered the first such number 561 in 1910. For many years it was an open problem as to whether there were infinitely many Carmichael numbers, but this was settled in 1994 by W R Alford, A Granville, and C Pomerance in their paper There are infinitely many Carmichael numbers.

Carmichael was elected a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. The Association was divided into two Sections, namely Section A covering Mathematics, Astronomy, Physics, Chemistry and Mineralogy, and Section B covering Geology, Zoology, Botany and Anthropology. Carmichael was Vice President of Section A in 1934. He also served the American Mathematical Society being on the Council in 1916-18, 1920, 1924, and 1925-27. He was Vice President of the Mathematical Association of America in 1921-23 and President in 1923. He served on the National Research Council from 1929 to 1932.

In addition to the very considerable mathematical output by Carmichael, he also served the mathematical community by undertaking editorial duties. He was Associative Editor of the Annals of Mathematics during 1916-18, and of the American Mathematical Monthly during 1916-17. He was editor-in-chief of theAmerican Mathematical Monthly in 1918. He also served as Editor of the Transactions of the American Mathematical Society from 1931 to 1936.

Let us end this biography by giving a quote from his friend Harrison E Cunningham:-

Of unyielding integrity, [Carmichael] loved the truth and hated sham and pretense. His appreciation of the beautiful, the true, and the good is exceptional. His friendship is firm, his loyalty unbreakable. Those who know him are fortunate beyond words.

Articles:

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي ينظّم ندوة حوارية حول مفهوم العولمة الرقمية في بابل

|

|

|