Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Context

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P119-C5

2025-03-10

755

Context

Although we have talked about the characteristics of different sounds in a spectrographic display, there are no absolute criteria that could uniquely define what a sound /X/ is in all phonetic environments, even for a particular individual. Thus, the lay person’s assumption that phonemes exhibit ‘invariance’ can hardly be justified.

Several factors influence both vowels and consonants. Earlier (see Diphthongs Table 1), we saw that the duration of vowels is different in stressed and unstressed syllables. Besides this, other variables are important too. One of the frequently mentioned variables is the influence of the following consonant, because the same vowel may be significantly longer before a voiced consonant than before a voiceless consonant.

The effect of the following consonant on the duration of the preceding vowel is mentioned above. In fact, this effect is also observed in all preceding sonorant segments. If we look at the spectrograms of the pairs sent– send, and kilt– killed (figure 1), we can observe the differences in the durations of the vowels and the sonorant consonants before voiced and voiceless stops. As we can see, the durations of the vowels and the sonorant consonants are, expectedly, greater before /d/ than /t/.

Fricatives exert an even greater influence over vowels than stops. For ex ample, we get the following readings for the same vowel [Λ] depending on the nature of the following consonant. We found the following differences with the change in the following segment:

but [bΛt] (vowel length before a voiceless stop: 104 ms)

bud [bΛd] (vowel length before a voiced stop: 172 ms)

buzz [bΛz] (vowel length before a voiced fricative: 210 ms)

The length of the word, as well as its number of syllables, seems influential. For example, while we get a reading of 93 ms for the vowel [ɪ] in pick, it goes down to 56 ms in picky and to 37 ms in pickiness.

Position of the word in the phrase or in the sentence, the rate of speaking, the type of word, either topic or comment, all influence the duration significantly. For example, the vowels of the two words dog [ɔ] and man [æ] change their duration by between 20 ms and 65 ms in the following sentences:

Similarly, in a listing situation, the last item has greater duration. If we compare the following two sentences, we get different durational readings for peaches and oranges in their two locations:

(a) I like apples, oranges, and peaches.

(b) I like apples, peaches, and oranges.

For example, we get an average of 94 ms as the durational reading for the final [z] of oranges in sentence (a), which goes up to a 174-ms reading for the same sound in sentence (b). Pre-pausal (at the end of phrases, clauses, or sentences) stressed vowels seem to have the longest duration; this is diametrically opposed to vowels in function words. As a result, the duration of a vowel in the former position may be up to two or even three times that of the same vowel in the latter.

Consonants can also be influenced by the contexts in which they appear. We saw earlier that the aspiration of the voiceless stops varied according to the following segment. Specifically, there was a longer lag before a sonorant consonant (e.g. play [phl̥e]) than before a vowel (e.g. pay [phe̥]). As for their duration, fricatives are the consonants that are more consistently affected by the context. For example, we get readings of 196–231 ms for the /s/ of sub [sΛb], which goes up to 309–325 ms in final position in bus [bΛs]. Yet, when we place it at the end of the phrase take the bus, /s/ gives us a reading of 328–365 ms.

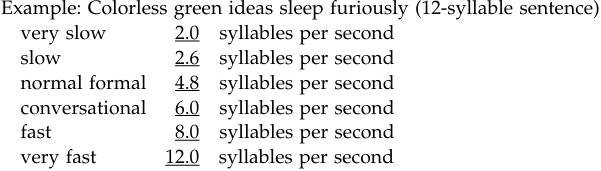

Speakers adapt to various circumstances of communication and adjust their production patterns accordingly. Thus, it is no surprise that speech style and rate influence the production, and we see a clear difference between slow, careful speech and fast, colloquial speech. While the former is characterized by a slower tempo, avoidance of reductions and/or deletions, and an attempt to make the production as distinct as possible, the latter is replete with deletions and reductions, and the durations of the components necessarily get shorter. These contrasting phenomena, which are known as hyperspeech (or “overshooting”) versus hypospeech (or “undershooting”), should not be conceived of as a binary split, but rather as a continuum (hence the terms ‘very slow’, ‘slow’, ‘normal formal’, ‘conversational’, ‘fast’, ‘very fast’). Consequently, the different speech realizations and different acoustic readings are the results of these varying production patterns.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)