Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Lexical Phonology and English /r/

المؤلف:

APRIL McMAHON

المصدر:

LEXICAL PHONOLOGY AND THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH

الجزء والصفحة:

P277-C6

2025-01-01

1374

Lexical Phonology and English /r/

Our next task is to assess where [r]-Insertion applies synchronically, in my model of Lexical Phonology. As we have seen earlier, lexical and postlexical rule applications are characterized by discrete sets of properties, which although not as decisively distinct as assumed in the early days of LP, when the division of lexical from postlexical rules was seen as absolute, nonetheless provide useful diagnostics for the level of application of rules, and for the historical movement into the lexicon characteristic of many low-level sound changes: the typical pathway represented by æ-Tensing (Harris 1989), schematized in (1).

(1)

Historically, æ-Tensing began as a Neogrammarian sound change, being purely phonetically conditioned; it then became a postlexical rule in some varieties of English, and a lexical rule in others. Ultimately, in some accents like RP, the rule itself is lost, although its effects are retained, being integrated into the underlying representations to encode a new distinction, in this case between /æ/ and /ɑ:/. If we were focusing on RP particularly, the diagram in (1) would show all the steps through which the variety had passed on its way to the present-day situation. Each step is also preserved in some variety of English.

However, not all sound changes seem to be incorporated into the grammar in the same way, and in Synchrony, diachrony and Lexical Phonology: the Scottish Vowel Length Rule, I identified an alternative pathway, this time involving the Scottish Vowel Length Rule. Historically, SVLR also began as a low-level process which lengthened vowels before voiced consonants. This sound change became the postlexical phonological rule of Low-Level Lengthening. However, in Scots and SSE, a rule inversion has occurred, such that an earlier, neutralizing process which shortened long vowels and lengthened short ones in opposing sets of contexts, became a lengthening process. This altered the underlying status of length in the affected varieties: vowels begin as contrastively long or short, but after the rule inversion, all are under lyingly short, with length supplied by rule in particular environments. Scots and SSE are now the only accents of English where vowel length is essentially predictable and non-contrastive, although more recent lexical diffusion of long [a:i] to forms like spider, viper, pylon may indicate the beginnings of a second change to the underlying representations, whereby /Λɪ/ and /a:i/ become distinctive. This means that contrastive length seems gradually to be being reintroduced, although SVLR is not simply reversing itself, since long and short vowels are not being restored to their earlier, historical distribution (2).

(2)

Since [r]-Insertion is also the result of a rule inversion, it might be expected to follow the same pathway as SVLR. We have established that /r/-Deletion was not a sudden change, but began as a low-level, general weakening, which ultimately resulted in loss of [r] in coda positions. The resulting phonological rule of /r/-Deletion was later converted, via rule inversion, into [r]-Insertion; and there is a concomitant change at the underlying level, as forms like spar, war, letter, which had underlying /r/ at the time of /r/-Deletion, lose it. Thus far, the progression from gradual sound change, to phonological rule, to a present-day, inverted version of this rule accompanied by an alteration in the underlying forms, mirrors the pathway followed by the SVLR. However, if [r]-Insertion does belong to the same class of processes as the SVLR, we should also be able to find some evidence of a second change at the underlying level during its history.

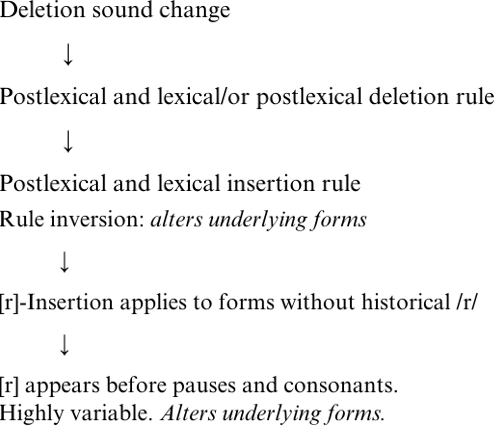

Such evidence may indeed exist, although, as for SVLR, it is fragmentary and highly variable. This involves the situation in New York City (Labov 1972), a previously non-rhotic area which has this century been progressively re-rhoticising, presumably because of influence from rhotic General American. Labov's work indicates that many speakers, as well as producing categorical [r] in linking [r] forms, giving a revised paradigm of war, warring, war is all with [r], have extended [r] to non-prepausal environments for intrusive [r] forms. Similarly, [r] is also found in preconsonantal environments with historical [r]; the combined influence of orthographic and rhotic General American speakers has reintroduced [r] in guard, heard, harp; but again, hypercorrection extends this into words with the same structure but without etymological [r], like god, which has [ɑ:] in New York speech. This might be interpreted as the provision of a new context for intrusive [r], but could equally indicate the acquisition of underlying /r/ in new forms. For instance, newly rhotic New York speakers may have guard and god, and law and lore, as homophones rather than minimal pairs; and if these have surface [r] in all contexts, we must assume underlying /r/. This sort of data is precisely parallel to our findings for the SLVR, where a second alteration in the underlying representations again gave new, unhistorical or counterhistorical forms, and again seemed to operate by gradual lexical diffusion. The steps in the history of [r] suggested by these examples is set out in (3).

(3)

As (3) shows, we begin, for non-rhotic varieties, with a deletion sound change, which becomes a phonological deletion rule, and is then inverted into an insertion rule; at this point, the underlying representations are altered as underlying non-prevocalic /r/ is lost, whereupon the inserted [r] is generalized to forms without historical /r/. The final step, which is by no means settled, involves the inclusion of underlying /r/ in forms which did not have it historically, and where it would not be inserted by the rule. As we have seen, this parallels the ongoing development of /a:i/ in Scots. Furthermore, as with ñ-Tensing and the SVLR, each step after the first in (3) is preserved in some varieties of English: dialects with linking [r] only would maintain the deletion process; those with linking and intrusive [r] have insertion; and it may be that re rhoticizing varieties exemplify the last stage.

Synchronically, for a variety with linking and intrusive [r], it seems that [r]-Insertion must apply postlexically, since it operates across word boundaries in fear of flying or severe attack, but also on both Levels 1 and 2. It operates regularly in Level 2 derived forms like soaring, saw[r]ing, banana[r]y. As for Level 1, we saw in McCarthy (1991) that [r] Insertion applies in doctoral, dangerous and severity, and that in the last case it must be ordered before Level 1 Trisyllabic Laxing. In apparent counterexamples like algebraic, ideal, dramatic, [r]-Insertion is either blocked by tensing rules, or by pre-existing, alternative derived forms. [r] Insertion therefore applies throughout the derivation, at Levels 1 and 2 as well as postlexically.

However, the earlier stage of /r/-Deletion may not have applied lexically. Certainly on Level 1, the Derived Environment Condition would have ruled it out: recall that [r] is not deleted in derived environments - rather, the derived environment is required for the retention of [r], by resyllabification into an adjacent onset. Consequently, /r/-Deletion may indeed have been a solely postlexical process, bringing the historical pathway followed by [r]-Insertion and associated processes even closer to that of the SVLR and its postlexical lengthening source. Both differ from the standard pathway of sound change - postlexical rule - lexical rule - incorporation into the underlying forms, as represented by æ-Tensing, by incorporating an extra step: they cause two changes in the underlying representations, not one. The first takes place at the time of the rule inversion; the second is later, and involves a gradual generalization of the inserted or derived sound into new underived environments, where it would not appear according to the rule. Thus, a series of regular steps leads to apparently odd irregularities. The case of /r/ therefore also supports my earlier suggestion that the processes falling into this second class, which alter the underliers twice in their life-cycle, may be those which would have been analyzed in Standard Generative Phonology as involving a rule inversion.

There remains, however, a disparity in the analysis here. I have argued for a gestural, Articulatory Phonology analysis of [r]-Deletion, but have only stated present-day [r]-Insertion as segment-based (∅ → r/ /ɑ: ɔ: ə/ ̶ V). How far is the commitment to gestures intended to go? In fact, dealing with this sort of insertion process using Articulatory Phonology is not straightforward, and requires revision of the model in various possible ways, precisely because there is no synchronic source in the immediate context for the gestures comprising [r], and Articulatory Phonology as currently formulated does not permit direct insertion or deletion of gestures.

There is strong evidence that `real' phonological processes exist, which nonetheless are unanalyzable in Articulatory Phonology in its currently constrained state. That is, although Articulatory Phonology can deal enlighteningly with fast and casual speech processes and the sound changes to which these give rise, the very limited gestural manipulations permitted by Browman and Goldstein are not sufficient to deal with the subsequent phonological rule stage in all cases. For instance, Nolan (1993) and Holst and Nolan (1995) consider assimilatory behavior of /s/ before [ʃ] in contexts like restocks shelves, based on visual reading of spectrograms. They report four categories of results: type A involved [s], with no assimilation; B and C had intermediate degrees of assimilation, with or without an initial partial [s]; but for type D, there was full assimilation, and the output of [ʃ] showed no trace of [s]. Holst and Nolan (1995) argue that types B and C can be dealt with under the Articulatory Phonology assumptions of gestural blending, but that type D must be seen as a higher-level, cognitive process replacing /s/ with /ʃ/ pre-production. This argument is supported by the electropalatographic results reported in Nolan, Holst and Kühnert (1996), who claim that Articulatory Phonology requires some supplementary mechanism to model `arbitrary facts about the sound patterns of a language ± by name, the phonological rule' (1996: 127).

The question is what form this supplement should take. Zsiga (1993, 1997), working on the basis of parallel gradient versus categorical processes in English and Igbo, argues that the difference lies in the units: gestures are needed at the postlexical level, but feature geometries have to be assumed lexically. Because gestures involve specification of actual extent in time, they can be used to model gradient phenomena, whereas features encode only simultaneity and precedence. At the output of the lexicon, a mapping of autosegmental features onto gestures takes place, partly on universal and partly on language-specific grounds. Conversely, McMahon, Foulkes and Tollfree (1994) contend that gestures should be adopted as the primary phonological unit at all levels, lexical and postlexical, and that the gradient versus categorical distinction resides in different constraints on rule application at different levels. Browman and Goldstein (1991: 334) already accept that `some phonological alternations are so complex as to not permit an adequate description using gestural principles', and specifically note that cases of rule inversion are likely to represent one case where `other principles or sources of constraint are ... required to completely explicate patterns in phonology'. These `other principles' could be promoted on an ad hoc basis, but McMahon, Foulkes and Tollfree (1994) argue that it is less arbitrary, as well as not requiring a complete withdrawal of the accepted conditions on gestural manipulations, to exploit the existing lexical - postlexical division and the well-known limitations on lexical rule applications, notably the Derived Environment Condition. A good deal of further work will be required to determine which approach is the right one, or whether aspects of both need to be integrated into the eventual composite lexical-articulatory model: we need to know more about the gestural configuration of vowels and of the different realizations of English /r/, the latter badly requiring experimental work; and it is also not clear that the boundary between the two types of constraints on gestural processes should be at the output of the lexicon, given that [r]-Insertion itself applies across word-boundaries and in view of the affinities Carr (1991) notes between lexical and early postlexical rules. But all this is work for the future.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)