Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-08-17

Date: 2023-10-09

Date: 2023-09-20

|

A derivational process is semantically regular if the contribution that it makes to the meaning of the lexemes produced by it is uniform and consistent. An example is adverb-forming -ly. This is not only formally regular (like -ness) but also semantically regular, in that it almost always contributes the meaning ‘in an X fashion’ or ‘to an X degree’. Semantic and formal regularity can diverge, however. Again, the suffix -ity provides handy illustration. As we have seen, -ity nouns are formally regular when derived from adjectives with a range of suffixes such as -ive, -al and -ar, and the nouns selectivity, locality, partiality and polarity all exist. It may strike you, however, that none of these nouns means exactly what one might expect on the basis of the meaning of the base adjective. Selectivity has a technical meaning related to radio reception, not shared with selectiveness, which has only the expected non-technical meaning. The adjective local can mean ‘confined to small areas’, but locality means never ‘confinement to small areas’ but always ‘neighborhood’. The noun partiality can mean either ‘incompleteness’ or ‘favorable bias’, just as partial can mean either ‘incomplete’ or ‘biased’; however, the noun more often has the second meaning while the adjective more often has the first. And one can use the noun polarity in talking about electric current, but not in talking about the climate in Antarctica.

Similar behavior is exhibited by the adjective-forming suffix -able. This is formally regular and general; the bases to which it can attach are transitive verbs, and there is scarcely any transitive verb for which a corresponding adjective in -able is idiosyncratically lacking, including a brand-new verb such as de-Yeltsinise. We have already drawn attention to the fact that -able adjectives can exhibit semantic irregularity, as readable and punishable do. In the same exercise, too, we noted that words formed with the suffix -ion and even some words with the formally highly regular -ly and -ness are not entirely predictable in meaning.

This divergence between formal and semantic regularity in derivation contrasts sharply with how inflection behaves. There, semantic regularity is the norm even where formal processes differ; for example, no past tense form of a verb has any unexpected extra meaning or function, whether it is formally regular (e.g. performed) or irregular (e.g. brought, sang). This contrast is not so surprising, however, if one remembers that word forms related by inflection are all forms of one lexeme, and therefore necessarily belong to one lexical item, whereas word forms related by derivation belong to different lexemes and therefore, at least potentially, different lexical items. Although, a lexeme does not necessarily have to be listed in a dictionary, lexemes have a kind of independence from one another that allows them to drift apart semantically, even though it does not require it.

Another illustration of how semantic and formal regularity can diverge is supplied by verbs with the bound root -mit. We noted that the three nouns commitment, committal and commission all have meanings related to meanings of the verb commit, but the distribution of these meanings among the three nouns is not predictable in a way that would allow an adult learner of English to guess it. Also, there is no way that a learner could guess that commission can also mean ‘payment to a salesperson for achieving a sale’, because this is not obviously related to any meaning of the verb. It follows that the suffixation of -ion is by no means perfectly regular semantically. But consider its formal status, by comparison with other noun-forming suffixes, as shown in (1):

(The question marks indicate words which are not in my active vocabulary but which I would not be surprised to hear; indeed, transmittance exists as a technical term in physics, meaning ‘measure of the ability to transmit radiation’.) The pattern of ticks, question marks and gaps seems random – except for the consistent ticks in the -ion column. It seems that -ion suffixation is formally regular with the root -mit; that is, for any verb with the root -mit, there is guaranteed to be a corresponding abstract noun in -mission. That being so, it seems natural to expect that the meanings of these nouns should be entirely regular. Yet we have already seen that for commission this is not so. Remission, too, is semantically irregular, in that the meanings of remit and -ion are not sufficient to determine the sense ‘temporary improvement during a progressive illness’. So the fact that a noun in -mission is guaranteed to exist for every verb in -mit does not mean that, for any individual such noun, a speaker who encounters it for the first time will be able to predict confidently what it means.

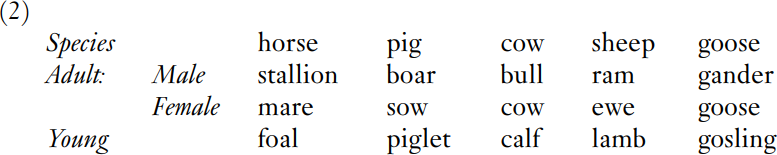

The converse of the situation just described would be one in which a number of different lexemes (not just inflectional forms of lexemes) exhibit a regular pattern of semantic relationship, but without any formally regular derivational processes accompanying it. Such a situation exists with some nouns that classify domestic animals according to sex and age:

Not many areas of vocabulary have such a tight semantic structure as this. However, the existence of just a few such areas shows that reasonably complex patterns of semantic relationship can sustain themselves without morphological underpinning. Morphology may help in expressing such relationships (as with pig and piglet, goose and gosling), but it is not essential. This reinforces further the need to distinguish between two aspects of ‘productivity’: formal and semantic regularity.

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي ينظّم ندوة حوارية حول مفهوم العولمة الرقمية في بابل

|

|

|