Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Phonological alternations

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

171-6

5-4-2022

1740

Phonological alternations

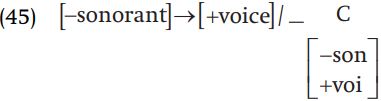

Voicing assimilation. As for the choice between an underlying voiced or voiceless consonant in the prefix, scanning the data reveals that a voiced consonant appears before voiced obstruents and a voiceless consonant appears before voiceless obstruents and sonorants. Since sonorants are phonetically voiced, it is clear that there is no natural context for deriving the voiceless consonant [t], so we assume that the prefix is underlyingly /it/. Before a voiced obstruent, a voiceless obstruent becomes voiced.

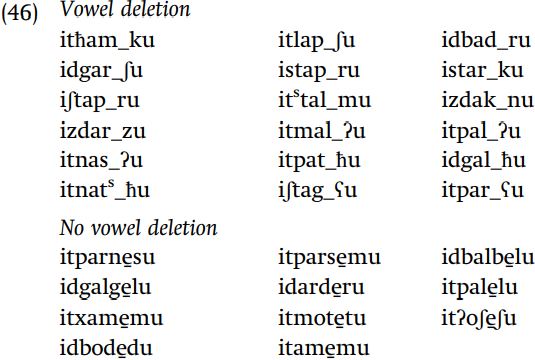

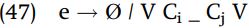

Alternations in V2. The second vowel of the stem has three phonetic variants: [a] as in itparnasti, [e] as in itparnes, and Ø as in idbadru (cf. idbader). Deletion of the second stem vowel only takes place before the suffix -u, so we will first attempt to decide when the vowel is deleted. A partial specification of the context for vowel deletion is before C+V, which explains why the first- and second-person-singular masculine forms (with the suffixes -it and -Ø) do not undergo vowel deletion. The next step in determining when a vowel is deleted is to sort the examples into two groups: those with vowel deletion and those with no vowel deletion. In the following examples, the site of vowel deletion (or its lack) is marked with an underscore.

Based on this grouping, we discover a vowel is deleted when it is preceded by just a single consonant; if two consonants precede the vowel, there is no deletion.

However, it is not always the case that a vowel deletes after a single consonant, so our rule cannot simply look for one versus two consonants. There are cases such as itʔoʃeʃu where there is no vowel deletion, despite the fact that there is only a single consonant before the vowel. Inspecting all of those examples, we discover that the consonants preceding and following the vowel are the same, and in every case where a vowel is deleted, the preceding and following consonants are different. Thus, a vowel deletes only if it is preceded by a single consonant, and that consonant must be different from the consonant that follows the vowel (which is indicated informally as “Ci ... Cj,” in the rule).

At this point, we now clearly recognize this process as a kind of syncope, a phonological rule which we have encountered many times before.

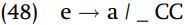

Closed syllable lowering. Now we turn to the alternation between [a] and [e]. Concentrating on the first set of examples in the data set, we find [a] before CC (itparnasti), and [e] before C# or CV (itparnes, itparnesu). Assuming that this distribution is generally valid, we would therefore posit the following rule to derive [a] from /e/.

An attempt to derive [e] from underlying /a/ runs into the difficulty that the context “when followed by C# or CV” is not a coherent context, but is just a set of two partially related contexts. This motivates the decision to select underlying /e/.

In four examples, the second stem vowel /e/ appears as [a] before a single consonant, namely the first-person-singular forms itmotati, idbodati, iʃtagati and itparati. These examples fall into two distinct subgroups, as shown by looking at their underlying stems, which is revealed in the third-singular feminine forms (itmotet-u, idboded-u and iʃtagʕu, itparʕu). In the first two examples the stems underlyingly end in a coronal stop t or d, and in the second two examples the stems underlyingly end in the voiced pharyngeal ʕ. At the underlying level, the second stem vowel is followed by two consonants (/itmotetti/, /itbodedti/, /iʃtageʕti/, and /itpareʕti/). Surface [a] is explained on the basis of the underlying consonant cluster – it must simply be assured that the rules simplifying these clusters apply after (48).

In the first two examples (itmotati and idbodati from /itmotat-ti/ and /idbodad-ti/) combination of the first-singular suffix with the root would (after assimilation of voicing) be expected to result in *itmotatti and *idbodatti. In fact, the data provide no examples of geminate consonants, and where geminates might have been created by vowel syncope in idbodedu, syncope is blocked. Thus, the language seems to be pursuing a strategy of avoiding the creation of geminate consonants. We can account for this simplification of consonant clusters by the following rule.

This rule also explains itamem and idarder, where the stem begins with /t/ or /d/. The underlying forms would be /it-tamem/ and /it-darder/: the surface form with a single consonant reflects the application of this consonant-degemination process.

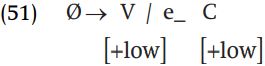

Stems with final pharyngeals and laryngeals. The vowel quality of /ʃageʕ/ and /pareʕ/ will be left aside temporarily. We thus turn to the stems represented in itpataħti, idgalaħti, and itnats aħti. What is problematic about these stems is the appearance of [ea] when no suffix is added, viz. itpateaħ, idgaleaħ, and itnats aħ. Assuming the underlying forms to be itpataħ, idgalaħ, and itnats eħ (selecting /e/ as the second vowel, analogous to itparnes, itlabeʃ, and idboded), we would need a rule inserting the vowel [a]. These stems have in common that their final consonant is the pharyngeal [ħ], suggesting a rule along the following lines.

Why does this rule only apply in the suffixless second-singular masculine form? When the stem is followed by -u (/itpateħu/ ! [itpatħu]) the vowel /e/ is deleted by the syncope rule, so there is no vowel before ħ. Syncope does not apply before the suffix -ti in /itpateħti/ ! [itpataħti] but there is still no epenthetic vowel. The reason is that underlying /e/ changes to [a] by rule (48), before a cluster of consonants. Since that rule changes /e/ to [a] but (50) applies after e, prior application of (50) deprives vowel insertion of a chance to apply.

Now returning to the stems ʃageʕ and pareʕ, we can see that this same process of vowel insertion applies in these stems in the second-singular masculine. Starting from /iʃtageʕ/ and /itpareʕ/, vowel epenthesis obviously applies to give intermediate iʃtageaʕ and itpareaʕ. This argues that the epenthesis rule should be generalized so that both of the pharyngeal consonants trigger the process.

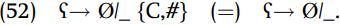

The forms derived by (51) are close to the actual forms, which lack the consonant ʕ, and with an appropriate consonant deletion rule we can finish the derivation of these forms. To formalize this rule, we need to determine where the consonant ʕ appears in the language: our data indicate that it appears only before a vowel, never before a consonant or at the end of a word (which is to say it never appears at the end of a syllable). Knowing this generalization, we posit the following rule.

No further rules are needed to account for this set of examples. In iʃtagati and itparati, from iʃtageʕti and itpareʕti, there is no epenthetic vowel. This is predicted by our analysis, since these verbs must undergo the rule lowering /e/ to [a] before CC, and, as we have just argued, vowel lowering precedes vowel epenthesis (thus preventing epenthesis from applying). In this respect, iʃtagati and itparati are parallel to itpateah, idgaleaħ, and itnats eaħ. The nonparallelism derives from the fact that syllable-final ʕ is deleted, so predicted *iʃtagaʕti and *itparaʕti are realized as iʃtagati and itparati thanks to this deletion.

The final set of verb stems typified by the verb itmaleti ~ itmale ~ itmalʔu exhibit a glottal stop in some contexts and Ø in other contexts. The two most obvious hypotheses regarding underlying form are that the stem is /male/, or else /maleʔ/. It is difficult to decide between these possibilities, so we will explore both. Suppose, first, that these stems end in glottal stop. In that case, we need a rule deleting glottal stop syllable-finally – a similar rule was required to delete the consonant ʔ. A crucial difference between stems ending in ʔ and stems presumably ending in ʔ is that the stem vowel /e/ does not lower to [a] before -ti in the latter set. Thus, deletion of ʔ would have to be governed by a different rule than deletion of ʔ, since ʔ-deletion precedes lowering and ʔ-deletion follows lowering.

An alternative possibility that we want to consider is that these stems really end in a vowel, not a glottal stop. Assuming this, surface [itpaleti] would simply reflect concatenation of the stem /pale/ with the suffix, and no phonological rule would apply. The problem is that we would also need to explain why the rule of syncope does not apply to [itpaleti], since the phonetic context for that rule is found here. The glottal-final hypothesis can explain failure of syncope rather easily, by ordering glottal stop deletion after syncope – when syncope applies, the form is /itpaleʔti/, where the consonant cluster blocks syncope.

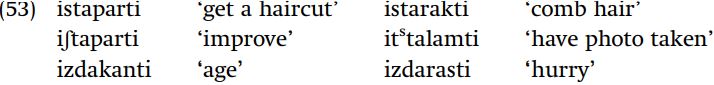

Metathesis. The last point regarding the Hebrew data is the position of t in the prefix. The consonant of the prefix actually appears after the first consonant of the stem in the following examples.

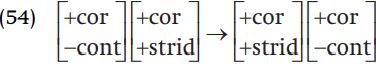

We would have expected forms such as [itsaparti], [itʃaparti], [itts alamti] by just prefixing it- to the stem. A metathesis rule is therefore needed which moves t after the stem-initial consonant. What makes this group of consonants – [s, ʃ, ts , z] – a natural class is that they are all and the only strident coronals. We can thus formalize this rule as follows: a coronal stop followed by a coronal strident switch order.

The ordering of this metathesis rule with respect to the voicing assimilation rule is crucial. Given underlying /it-zakanti/, you might attempt to apply metathesis first, which would yield iztakanti, where voiceless t is placed after stem-initial z. The voicing assimilation rule (in a general form, applying between all obstruents) might apply to yield *istakanti. So if metathesis applies before voicing assimilation, we will derive an incorrect result, either *iztakanti if there is no voicing assimilation (assuming that the rule only turns voiceless consonants into voiced ones) or *istakanti if there is voicing assimilation. However, we will derive the correct output if we apply voicing assimilation first: /itzakanti/ becomes idzakanti, which surfaces as [izdakanti] by metathesis. With this ordering, we have completed our analysis of Modern Hebrew phonology.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)