Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Bukusu: nasal+consonant combinations

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

121-5

29-3-2022

4734

Bukusu: nasal+consonant combinations

The theme which we have been developing is that phonological grammars are composed of simple rule elements that interact in ways that make the data patterns appear complicated, and factoring out of the fundamental processes is an essential part of phonological analysis. In the examples which we have considered above, such as vowel raising/fronting and velar palatalization in Votic, or glide formation and palatalization in Kamba, the phonological processes have been sufficiently different that no one would have problems seeing that these are different rules. A language may have phonological changes which seem similar in nature, or which apply in similar environments, and the question arises whether the alternations in question reflect a single phonological rule. Or, do the alternations reflect the operation of more than one independent rule, with only accidental partial similarity? Such a situation arises in Bukusu (Kenya), where a number of changes affect sequences of nasal plus consonant.

Nasal Place Assimilation and Post-Nasal Voicing. In the first set of examples in (12), a voicing rule makes all underlyingly voiceless consonants voiced when preceded by a nasal, in this case after the prefix for the first-singular present-tense subject which is /n/. The underlying consonant at the beginning of the root is revealed directly when the root is preceded by the third-plural prefix βa-, or when there is no prefix as in the imperative.

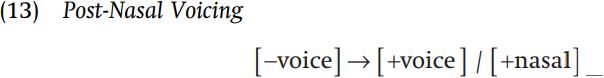

We can state this voicing rule as follows.

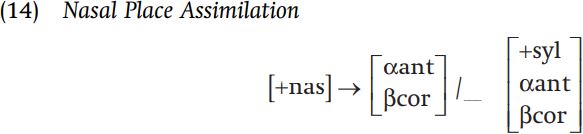

You will also note that a nasal consonant always agrees in place of articulation with the following consonant, due to the following rule.

The data considered so far have not given clear evidence as to what the underlying place of articulation of the first-singular subject prefix is, since that nasal always assimilates to the following consonant. To determine that the prefix is indeed /n/, we turn to the form of stems which underlyingly begin with a vowel, where there is no assimilation. In the imperative, where no prefix precedes the stem, the glide [ j] is inserted before the initial vowel. (The data in (17) include examples of underlying initial /j/, which is generally retained, showing that there cannot be a rule of j-deletion.) When the third-plural prefix /βa/ precedes the stem, the resulting vowel sequence is simplified to a single nonhigh vowel. No rules apply to the first-singular prefix, which we can see surfaces as [n] before all vowels.

One question that we ought to consider is the ordering of the rules of voicing and place assimilation. In this case, the ordering of the rules does not matter: whether you apply voicing first and assimilation second, or assimilation first and voicing second, the result is the same.

The reason why ordering does not matter is that the voicing rule does not refer to the place of articulation of the nasal, and the assimilation rule does not refer to the voicing of the following consonant. Thus information provided by one rule cannot change whether the other rule applie

Post-Nasal Hardening. Another process of consonant hardening turns voiced continuants into stops after a nasal: l and r become d, β becomes b, and j becomes dʒ .

These data can be accounted for by the following rule:

This formalization exploits the concept of structure preservation to account for the changes to /r, l, j/. By becoming [-cont], a change to [-son] is necessitated since there are no oral sonorant stops in Bukusu. Likewise the lack of lateral stops in the language means that /l/ becomes [-lat] when it becomes [-cont]. Since there is no segment [ɟ] in Bukusu, making /j/ become a stop entails a change in place of articulation from palatal to alveopalatal, and from plain stop to affricate.

The generalizations expressed in rules (13) and (18) can be unified into one even simpler rule, which states that consonants after nasals become voiced stops.

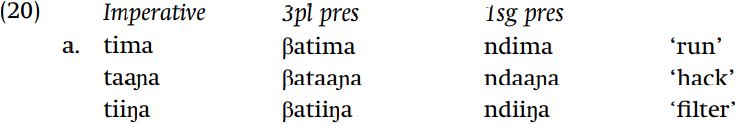

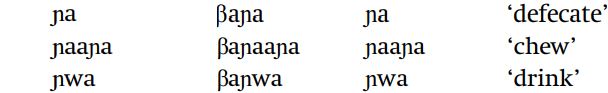

l-deletion. A third process affecting sequences of nasal plus consonant can be seen in the following data.

The examples in (a) show the effect of rules of voicing and consonant hardening, applying as expected to /t/ and /r/. However, the examples in (b) show the deletion of underlying /l/ after a nasal. These examples contrast with the first set of examples in (17), where the root also begins with underlying /l/: the difference between the two sets of verbs is that in the second set, where /l/ deletes, the following consonant is a nasal, whereas in the first set where /l/ does not delete, the next consonant is not a nasal.

The significance of the examples in (20a) is that although underlying /t/, /l/, and /r/ all become [d] after a nasal, the deletion of an underlying consonant in the environment N_VN only affects underlying /l/. Since the voicing-hardening rule (19) neutralizes the distinction between the three consonants after a nasal but in fact /l/ acts differently from /t/ and /r/ in the context N_VN, we can conclude that there is a prior rule deleting /l/ – but not /t/ or /r/ – in this context.

This rule clearly must apply before the hardening rule changes /l/ into [d] after a nasal, since otherwise there would be no way to restrict this rule to applying only to underlying /l/. When (19) applies, underlying /n-liinda/ would become n-diinda, but /n-riina/ would also become n-diina. Once that has happened, there would be no way to predict the actual pronunciations [niinda] versus [ndiina].

On the other hand, if you were to apply the l-deletion rule first, the rule could apply in the case of /n-liinda/ to give [niinda], but would not apply to /n-riina/ because that form does not have an l: thus by ordering the rules so that l-deletion comes first, the distinction between /l/, which deletes, and /r/, which does not delete, is preserved.

Nasal Cluster Simplification. Another phonological process applies to consonants after nasal consonants. When the root begins with a nasal consonant, the expected sequence of nasal consonants simplifies to a single consonant.

In the case of mala ‘I finish,’ the underlying form would be /n-mala/ which would undergo the place assimilation rule (14), resulting in *mmala. According to the data available to us, there are no sequences of nasals in the language, so it is reasonable to posit the following rule.

Nasal Deletion. The final process which applies to sequences of nasal plus consonant is one deleting a nasal before a voiceless fricative.

The underlying form of fuma ‘I spread’ is /n-fuma/ since the prefix for 1sg is /n-/ and the root is /fuma/, and this contains a sequence nasal plus voiceless fricative. Our data indicate that this sequence does not appear anywhere in the language, so we may presume that such sequences are eliminated by a rule of nasal deletion. The formulation in (25) accounts for the deletion facts of (24).

There can be an important connection between how rules are formulated and how they are ordered. In the analysis presented here, we posited the rules Nasal Deletion (25) and Post-Nasal Voicing-Hardening (19), repeated here, where Nasal Deletion applies first.

Since, according to (25), only voiceless continuants trigger deletion of a following nasal, we do not expect /n-βala/ ‘I count’ to lose its nasal. How-ever, there is the possibility that (19) could apply to /n-fwa/ ‘I die,’ since (19) does not put any conditions on the kind of consonant that becomes a voiced stop – but clearly, /f/ does not become a voiced stop in the surface form [fwa]. This is because Nasal Deletion first eliminates the nasal in /n-fwa/, before (19) has a chance to apply, and once the nasal is deleted, (19) can no longer apply.

You might consider eliminating the specification [-voice] from the formalization of (25) on the grounds that voiced continuants become stops by (19), so perhaps by applying (19) first, we could simplify (25). Such a reordering would fail, though, since (19) would not only correctly change /n-βala/ to [mbala], but would incorrectly change /n-fwa/ to *[mbwa]. The only way to eliminate the specification [-voice] in (25) would be to split (19) into two rules specifically applying to voiced continuants and voiceless stops – a considerable complication that negates the advantage of simplifying (25) by one feature specification.

Summary. We have found in Bukusu that there are a number of phonological processes which affect N+C clusters, by voicing, hardening, or deleting the second consonant, or deleting the nasal before a nasal or a voiceless fricative.

Despite some similarity in these processes, which involve a common environment of nasal-plus-consonant, there is no reasonable way to state these processes as one rule.

In addition to showing how a complex system of phonological alternations decomposes into simpler, independent, and partially intersecting rules, the preceding analyses reveal an important component of phonological analysis, which is observing regularities in data, such as the fact that Bukusu lacks any consonant sequences composed of a nasal plus a fricative on the surface.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)