Place of articulation

Features to define place of articulation are our next functional set. We begin with the features typically used by vowels, specifically the [+syllabic, -consonantal, +sonorant] segments, and then proceed to consonant features, ending with a discussion of the intersection of these features.

Vowel place features. The features which define place of articulation for vowels are the following.

High: the body of the tongue is raised from the neutral position.

Low: the body of the tongue is lowered from the neutral position.

Back: the body of the tongue is retracted from the neutral position.

Round: the lips are protruded.

tense: sounds requiring deliberate, accurate, maximally distinct gestures that involve considerable muscular effort.

advanced tongue root: produced by drawing the root of the tongue forward.

The main features are [high], [low], [back], and [round]. Phonologists primarily distinguish just front and back vowels, governed by [back]: front vowels are [-back] since they do not involve retraction of the tongue body, and back vowels are [+back]. Phonetic central vowels are usually treated as phonological back vowels, since typically central vowels are unrounded and back vowels are rounded. Distinctions such as those between [ɨ] and [ɯ], [ɜ] and [ʌ], [y] and [ʉ], [ʚ] and [œ], or [a] and [ɑ] are usually considered to be phonologically unimportant over-differentiations of language-specific phonetic values of phonologically back unrounded vowels. The phonologically relevant question about a vowel pronounced as [ʉ] is not whether the tongue position is intermediate between that of [i] and [u], but whether it patterns with {i, e, y, ø} or with {u, ɯ, o, ʌ} – or does it pattern apart from either set? In lieu of clear examples of a contrast between central and back rounded vowels, or central and back unrounded vowels, we will not at the moment postulate any other feature for the front–back dimension: Given the phonologically questionable status of distinctive central vowels, no significance should be attributed to the use of the symbol [ɨ] versus [ɯ], and typographic convenience may determine that a [+back, -round] high vowel is typically transcribed as [ɨ].

Two main features are employed to represent vowel height. High vowels are [+high] and [-low], low vowels are [+low] and [-high]. No vowel can be simultaneously [+high] and [+low] since the tongue cannot be raised and lowered simultaneously; mid vowels are [-high, -low]. In addition, any vowel can be produced with lip rounding, using the feature [round]. These features allow us to characterize the following vowel contrasts.

Note that [ɑ] is a back low unrounded vowel, in contrast to the symbol [ɒ] for a back low rounded vowel.

Vowels with a laxer, “less deliberate,” and lower articulation, such as [ɪ] in English sit or [ε] in English set, would be specified as [-tense].

Korean has a set of so-called “tense” consonants but these are phonetically “glottal” consonants.

One question which has not been resolved is the status of low vowels in terms of this feature. Unlike high and mid vowels, there do not seem to be analogous contrasts in low vowels between tense and lax [æ]. Another important point about this feature is that while [back], [round], [high], and [low] will also play a role in defining consonants, [tense] plays no role in consonantal contrasts.

The difference between i and ɪ, or e and ε has also been considered to be one of vowel height (proposed in alternative models where vowel height is governed by a single scalar vowel height feature, rather than by the binary features [high] and [low]). This vowel contrast has also been described in terms of the feature “Advanced Tongue Root” (ATR), especially in the vowel systems of languages of Africa and Siberia. There has been debate over the phonetic difference between [ATR] and [tense]. Typically, [+tense] front vowels are fronter than their lax counterparts, and [+tense] back vowels are backer than their lax counterparts. In comparison, [+ATR] vowels are supposed to be generally fronter than corresponding [-ATR] vowels, so that [+ATR] back vowels are phonetically fronter than their [-ATR] counterparts. However, some articulatory studies have shown that the physical basis for the tense/lax distinction in English is no different from that which ATR is based on. Unfortunately, the clearest examples of the feature [ATR] are found in languages of Africa, where very little phonetic research has been done. Since no language contrasts both [ATR] and [tense] vowels, it is usually supposed that there is a single feature, whose precise phonetic realization varies somewhat from language to language.

Consonant place features. The main features used for defining consonantal place of articulation are the following.

coronal: produced with the blade or tip of the tongue raised from the neutral position.

anterior: produced with a major constriction located at or in front of the alveolar ridge.

strident: produced with greater noisiness.

distributed: produced with a constriction that extends for a considerable distance along the direction of airflow.

Place of articulation in consonants is primarily described with the features [coronal] and [anterior]. Labials, labiodentals, dentals, and alveolars are [+anterior] since their primary constriction is at or in front of the alveolar ridge (either at the lips, the teeth, or just back of the teeth) whereas other consonants (including laryngeals) are [-anterior], since they lack this front constriction. The best way to understand this feature is to remember that it is the defining difference between [s] and [ ʃ], where [s] is [+anterior] and [ ʃ] is [-anterior]. Anything produced where [s] is produced, or in front of that position, is [+anterior]; anything produced where [ ʃ] is, or behind [ ʃ], is [-anterior]

Remember that the two IPA letters represent a single [-anterior] segment, not a combination of [+anterior] [t] and [-anterior] [ ʃ].

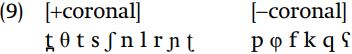

Consonants which involve the blade or tip of the tongue are [+coronal], and this covers the dentals, alveolars, alveopalatals, and retroflex consonants. Consonants at other places of articulation – labial, velar, uvular, and laryngeal – are [-coronal]. Note that this feature does not encompass the body (back) of the tongue, so while velars and uvulars use the tongue, they use the body of the tongue rather than the blade or tip, and therefore are [-coronal]. The division of consonants into classes as defined by [coronal] is illustrated below.

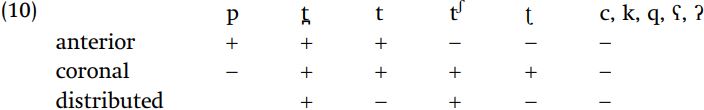

Two other features are important in characterizing the traditional places of articulation. The feature [distributed] is used in coronal sounds to distinguish dental [t̪] from English alveolar [t], or alveopalatal [ ʃ] from retroflex [ʂ]: the segments [t̪, ʃ] are [+distributed] and [t, ʈ, ʂ] are [-distributed]. The feature [distributed], as applied to coronal consonants, approximately corresponds to the traditional phonetic notion “apical” ([-distributed]) versus “laminal” ([+distributed]). This feature is not relevant for velar and labial sounds and we will not specify any value of [distributed] for noncoronal segments.

The feature [strident] distinguishes strident [f, s] from nonstrident [φ, θ]: otherwise, the consonants [f, φ] would have the same feature specifications. Note that the feature [strident] is defined in terms of the aerodynamic property of greater turbulence (which has the acoustic correlate of greater noise), not in terms of the movement of a particular articulator – this defining characteristic is accomplished by different articulatory configurations. In terms of contrastive usage, the feature [strident] only serves to distinguish bilabial and labiodentals, or interdentals and alveolars. A sound is [+strident] only if it has greater noisiness, and “greater” implies a comparison. In the case of [φ] vs. [f], [β] vs. [v], [θ] vs. [s], or [ð] vs. [z] the second sound in the pair is noisier. No specific degree of noisiness has been proposed which would allow you to determine in isolation whether a given sound meets the definition of strident or not. Thus it is impossible to determine whether [ ʃ] is [+strident], since there is no contrast between strident and nonstrident alveopalatal sounds. The phoneme [ ʃ] is certainly relatively noisy – noisier than [θ] – but then [θ] is noisier than [φ] is.

[Strident] is not strictly necessary for making a distinction between [s] and [θ], since [distributed] also distinguishes these phonemes. Since [strident] is therefore only crucial for distinguishing bilabial and labial fricatives, it seems questionable to postulate a feature with such broad implications solely to account for the contrast between labiodental and bilabial fricatives. Nonetheless, we need a way of representing this contrast. The main problem is that there are very few languages (such as Ewe, Venda, and Shona) which have both [f] and [φ], or [v] and [β], and the phonological rules of these languages do not give us evidence as to how this distinction should be made in terms of features. We will therefore only invoke the feature [strident] in connection with the [φ, β] vs. [f, v] contrast.

Using these three features, consonantal places of articulation can be partially distinguished as follows.

Vowel features on consonants. The features [high], [low], [back], and [round] are not reserved exclusively for vowels, and these typical vowel features can play a role in defining consonants as well. As we see in (10),

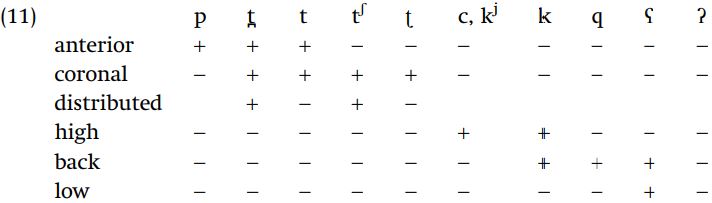

velar, uvular, pharyngeal, and glottal places of articulation are not yet distinguished; this is where the features [high], [low], and [back] become important. Velar, uvular, and pharyngeal consonants are [+back] since they are produced with a retracted tongue body. The difference between velar and uvular consonants is that with velar consonants the tongue body is raised, whereas with uvular consonants it is not, and thus velars are [+high] where uvulars are [-high]. Pharyngeal consonants are distinguished from uvulars in that pharyngeals are [+low] and uvulars are [-low], indicating that the constriction for pharyngeals is even lower than that for uvulars.

One traditional phonetic place of articulation for consonants is that of “palatal” consonants. The term “palatal” is used in many ways, for example the postalveolar or alveopalatal (palatoalveolar) consonants [ ʃ] and [tʃ ] might be referred to as palatals. This is strictly speaking a misnomer, and the term “palatal” is best used only for the “true palatals,” transcribed as [c ç ɟ]. Such consonants are found in Hungarian, and also in German in words like [iç] ‘I’ or in Norwegian [çø:per] ‘buys.’ These consonants are produced with the body of the tongue raised and fronted, and therefore they have the feature values [+high, -back]. The classical feature system presented here provides no way to distinguish such palatals from palatalized velars ([kj ]) either phonetically or phonologically. Palatalized (fronted) velars exist as allophonic variants of velars before front vowels in English, e.g. [kj ip] ‘keep’; they are articulatorily and acoustically extremely similar to the palatals of Hungarian. Very little phonological evidence is available regarding the treatment of “palatals” versus “palatalized velars”: it is quite possible that [c] and [kj ], or [ç] and [xj ], are simply different symbols, chosen on the basis of phonological patterning rather than systematic phonetic differences.

With the addition of these features, the traditional places of articulation for consonants can now be fully distinguished.

The typical vowel features have an additional function as applied to consonants, namely that they define secondary articulations such as palatalization and rounding. Palatalization involves superimposing the raised and fronted tongue position of the glide [ j] onto the canonical articulation of a consonant, thus the features [+high, -back] are added to the primary features that characterize a consonant (those being the features that typify [i, j]). So, for example, the essential feature characteristics of a bilabial are [+anterior, -coronal] and they are only incidentally [-high, -back]. A palatalized bilabial would be [+anterior, -coronal, +high, -back]. Velarized consonants have the features [+high, +back]

analogous to the features of velar consonants; pharyngealized consonants have the features [+back, +low]. Consonants may also bear the feature [round]. Applying various possible secondary articulations to labial consonants results in the following specifications.

Labialized ( pw), palatalized (pj ), velarized ( pγ ) and pharyngealized ( pʕ ) variants are the most common categories of secondary articulation. Uvularized consonants, i.e. pq , are rare: uvularized clicks are attested in Ju/’hoansi. It is unknown if there is a contrast between rounded consonants differing in secondary height, symbolized above as pw vs. po or pɥ vs. pø . Feature theory allows such a contrast, so eventually we ought to find examples. If, as seems likely after some decades of research, such contrasts do not exist where predicted, there should be a revision of the theory, so that the predictions of the theory better match observations.

This treatment of secondary articulations makes other predictions. One is that there cannot be palatalized uvulars or pharyngeals. This follows from the fact that the features for palatalization ([+high, -back]) conflict with the features for uvulars ([-high, +back]) and pharyngeals ([-high, +back, +low]). Since such segments do not appear to exist, this supports the theory: otherwise we expect – in lieu of a principle that prohibits them – that they will be found in some language. Second, in this theory a “pure” palatal consonant (such as Hungarian [ɟ]) is equivalent to a palatalized (i.e. fronted) velar. Again, since no language makes a contrast between a palatal and a palatalized velar, this is a good prediction of the theory (unless such a contrast is uncovered, in which case it becomes a bad prediction of the theory).

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة