Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Free variation, neutralization and morphophonemics

المؤلف:

April Mc Mahon

المصدر:

An introduction of English phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

88-7

19-3-2022

2033

Free variation, neutralization and morphophonemics

Some examples involving free variation between vowel phonemes were already reviewed : for instance, economic can be pronounced, for the same speaker, with the DRESS vowel on some occasions and the FLEECE vowel on others, and although this conflicts with the requirement that different phonemes should not be substitutable without causing a change in meaning to be conveyed, such a marginal case involving only a single lexical item should not in fact compromise the distinction between /ε/ and /i:/, given the significant number of minimal pairs establishing their contrast.

Free variation also occurs between allophones of a single phoneme. This again correlates with sociolinguistic rather than linguistic conditioning. For instance, in NZE some speakers produce , the NURSE vowel, with lip-rounding, more significantly so in informal circumstances. Similarly, New Yorkers may produce the FLEECE and GOOSE vowels as monophthongs in formal situations, but prefer diphthongs in casual speech; and the quality of the diphthongs varies too, with [Ii],

, the NURSE vowel, with lip-rounding, more significantly so in informal circumstances. Similarly, New Yorkers may produce the FLEECE and GOOSE vowels as monophthongs in formal situations, but prefer diphthongs in casual speech; and the quality of the diphthongs varies too, with [Ii], being more common for middle-class speakers, but more central first elements, and hence a greater distance between the two parts of the diphthongs, for working-class speakers. Some cases of free variation reflect language change in progress: so, in SSBE older speakers may still produce centring diphthongs in CURE and SQUARE words, while younger ones almost invariably smoothe these diphthongs out and produce monopthongal [ɔ:], [ε:]. Younger speakers might use the pronunciations more typical of the older generation when they are talking to older relatives, or in formal circumstances.

being more common for middle-class speakers, but more central first elements, and hence a greater distance between the two parts of the diphthongs, for working-class speakers. Some cases of free variation reflect language change in progress: so, in SSBE older speakers may still produce centring diphthongs in CURE and SQUARE words, while younger ones almost invariably smoothe these diphthongs out and produce monopthongal [ɔ:], [ε:]. Younger speakers might use the pronunciations more typical of the older generation when they are talking to older relatives, or in formal circumstances.

Cases of neutralization tend not to be subject to sociolinguistic influence in this way, but rather reflect a tendency for certain otherwise contrastive sets or pairs of vowels to fall together with a single realization in a particular phonological context. We saw that the DRESS, TRAP and SQUARE vowels are neutralized for many GA speakers before /r/, so that merry, marry and Mary become homophonous: in this context, rather than the usual opposition, we might propose archiphonemic /E/, realized as [ε]. Neutralizations of this sort are extremely common for English vowels. To take just two further examples, speakers from the southern states of the USA have a neutralization of the KIT and DRESS vowels before /n/, so that pin and pen are homophonous; and for many speakers of SSE and Scots, the opposition between the KIT and STRUT vowels is suspended before /r/, so that fir and fur are both pronounced with

opposition, we might propose archiphonemic /E/, realized as [ε]. Neutralizations of this sort are extremely common for English vowels. To take just two further examples, speakers from the southern states of the USA have a neutralization of the KIT and DRESS vowels before /n/, so that pin and pen are homophonous; and for many speakers of SSE and Scots, the opposition between the KIT and STRUT vowels is suspended before /r/, so that fir and fur are both pronounced with .

.

However, whereas suspension of contrast takes place in a particular phonological context, and will affect all lexical items with that context, in other cases we are dealing with an interaction of morphology and phonology; here, we cannot invoke neutralization. For instance, the discussion of the Scottish Vowel Length Rule above does not quite tell the full story, since we also find alternations of long and short vowels in the cases in (8).

From the Scottish Vowel Length Rule examples considered earlier, we concluded that vowel length is not contrastive in SSE and Scots, since it was possible to predict that long vowels appear before certain consonants or at the end of a word, while short ones appear elsewhere. However, the data in (8) appear, on purely phonological grounds, to constitute minimal pairs for short and long vowels. In fact, what seems to matter is the structure of the words concerned. The vowels in the ‘Long’ column of (8) are in a sense word-final; they precede the inflectional ending [d] marking past tense; or the suffix -ness; or appear at the end of the first element of a compound, which is a word in its own right, as in tie. This is not true for the ‘Short’ column, where the words are not separable in this way. The Scottish Vowel Length Rule must therefore be rewritten to take account of the morphological structure of words: it operates before /r/ and voiced fricatives, at the end of a word, and also at the end of a morpheme, or meaningful unit within the word; in the cases in (8), the affected vowel is at the end of a stem.

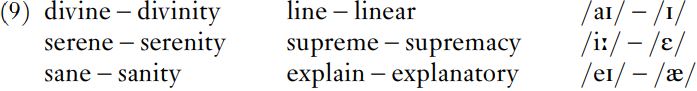

In other cases, different vowel phonemes alternate with one another before particular suffixes, as we found for consonants , where the final [k] of electric became [s] or [ʃ] before certain suffixes, as in electricity and electrician. One of the best-known cases in English, and one which affects all varieties, involves pairs of words like those in (9).

These Vowel Shift alternations (so-called because the patterns reflect the operation of a sound change called the Great Vowel Shift several hundred years ago) involve pairs of phonemes which very clearly contrast in English – the members of the PRICE and KIT, FLEECE and DRESS, and FACE and TRAP pairs of standard lexical sets. Minimal pairs are common for all of these (take type and tip, peat and pet, lake and lack, for instance). However, the presence of each member of these pairs can be predicted in certain contexts only; and native speakers tend to regard the pairs involved, such as divine and divinity, as related forms of the same word. This is not neutralization, because the context involved is not specifically phonetic or phonological: it is morphological. That is, what matters is not the length of the word, or the segment following the vowel in question, but the presence or absence of one of a particular set of suffixes. In underived forms (that is, those with no suffix at all) we find the tense or long vowel, here ;but in derived forms, with a suffix like -ity, -ar, -acy, -ation, a corresponding lax or short vowel /I/, /ε/ or

;but in derived forms, with a suffix like -ity, -ar, -acy, -ation, a corresponding lax or short vowel /I/, /ε/ or appears instead. This alternation is a property of the lexical item concerned; vowel changes typically appear when certain suffixes are added, but there are exceptions like obese, with /i:/ in the underived stem, and the same vowel (rather than the /ε/ we might predict) in obesity, regardless of the presence of the suffix -ity. Opting out in this way does not seem to be a possibility in cases of neutralization, but is quite common in cases of morphophonemics, or the interaction between phonology and morphology.

appears instead. This alternation is a property of the lexical item concerned; vowel changes typically appear when certain suffixes are added, but there are exceptions like obese, with /i:/ in the underived stem, and the same vowel (rather than the /ε/ we might predict) in obesity, regardless of the presence of the suffix -ity. Opting out in this way does not seem to be a possibility in cases of neutralization, but is quite common in cases of morphophonemics, or the interaction between phonology and morphology.

To put it another way, not all alternations involving morphology are completely productive. Some are: this means that every single relevant word of English obeys the regularity involved (so, all those nouns which form their plural using a -s suffix will have this pronounced as [s] after a voiceless final sound in the stem, [z] after a voiced one, and [Iz] after a sibilant; not only this, but any new nouns which are borrowed into English from other languages, or just made up, will also follow this pattern). Others are fairly regular, but not entirely so: this goes for the Vowel Shift cases above. And yet others are not regular at all, but are simply properties of individual lexical items which children or secondlanguage learners have to learn as such. The fact that teach has the past tense taught is an idiosyncrasy of modern English which has to be mastered; but although knowing this relationship will help a learner of English to use teach and taught appropriately, it will not help when it comes to learning other verbs, because preach does not have the past tense *praught, and caught does not have the present tense *ceach. Knowing where we should draw the line between extremely regular cases which clearly involve exceptionless rules or generalizations, fairly regular ones which may be stated as rules with exceptions, and one-off (or severaloff) cases where there is no rule at all but a good deal of rote-learning, is one of the major challenges of morphophonology. The only comfort is that native speakers, at least during acquisition and sometimes later too, find it just as much of a challenge, as amply demonstrated by overgeneralizations like past-tense swang from swing (on the pattern of swim – swam) or past-tense [trεt] from treat (on the pattern of meet – met).

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)