Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Variable telicity in degree achievements - Telicity and vagueness

المؤلف:

CHRISTOPHER KENNEDY AND BETH LEVIN

المصدر:

Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse

الجزء والصفحة:

P157-C7

2025-04-21

804

Variable telicity in degree achievements - Telicity and vagueness

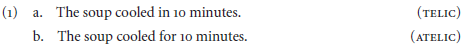

Vendler (1957) distinguishes atelic predicates (activities) like run from telic predicates (accomplishments) like run a mile on the basis of whether they entail of an event that a “set terminal point” has been reached. Most studies of variable telicity focus on contrasts like run for/??in four minutes vs. run a mile in/??for four minutes, because they show that compositional interactions between a verb and its argument(s) can affect the telicity of the predicate (Verkuyl 1972; Mourelatos 1978; Bach 1986; Krifka 1989). Degree achievements (DAs) present a special challenge, however, because they may have variable telicity independently of the properties of their arguments, as first observed by Dowty (1979). Consider for example the uses of cool in (1a–b).1

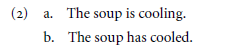

The acceptability of the in-PP in (1a) shows that cool can be telic, and indeed this sentence is true of an event only if it leads to an endstate in which the affected participant has come to be cool. However, the acceptable for-PP in (1b) shows that cool can also be atelic, and this example implies neither that the endstate associated with (1a) (“coolness”) has been reached, nor that a sequence of distinct change of state eventualities has taken place (as in iterated achievements like Kim discovered crabgrass in the yard for six weeks; see Dowty 1979). Similarly, whether or not the progressive form in (2a) entails the perfect in (2b) depends on whether we understand cool in (2a) only as implying that the temperature of the soup is getting lower (atelic; (2b) entailed), or as implying that the temperature of the soup is moving towards an understood endstate of being cool (telic; (2b) not entailed).

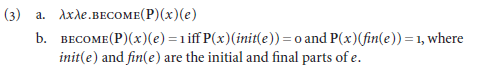

The challenge then is to identify the factors which lead to variable telicity in DAs. Building on ideas in Dowty (1979), Abusch (1986) proposes that the variable telicity of DAs (her “vague inchoatives”) is parasitic on a different kind of variability in the meanings of the expressions that describe the endstates such verbs imply (in their telic uses). Following Dowty, Abusch takes the lexical meaning of an inchoative verb to be as in (3a), where P is a property of individuals, with truth conditions as in (3b).2

Abusch observes that what is special about DAs like cool is that P corresponds to a vague predicate: what counts as cool is a matter of context, and there will typically be some things for which it is impossible to say whether they are cool or not (so-called “borderline cases”). Building on the analyses of vague predicates in Kamp (1975) and Klein (1980) (see also McConnell-Ginet 1973 and Fine 1975), Abusch analyzes adjectival cool as a function cool from contexts to properties of individuals, and proposes that the variability of verbal cool depends on whether the contextual argument of cool is fixed to the context of utterance, as in (4a), or is bound by an existential quantifier, as in (4b).

In (4a), cool(c u) is the property of being cool in the context of utterance. This is the meaning of the positive (unmarked) form of the adjective, which is true of objects that are at least as cool as some contextual “standard” of temperature. (The standard can vary both on properties of the object and on properties of the context: cool lemonade is normally cooler than cool coffee, and coffee that counts as cool relative to one’s desire to drink it in the morning with a bagel is typically warmer than coffee that counts as cool relative to one’s desire to pour it over ice without turning the whole thing into a watery mess.) Saturation of the individual argument x derives a property that is true of an event just in case x is not as cool as the contextual standard at the beginning of the event, and is at least as cool as the standard at the end of the event; the requirement that this transition be made renders the predicate telic.

In (4b), the context variable is existentially bound, which means that the predicate is true of an event just in case there is some context such that x is not cool relative to that context at the beginning of the event and is cool relative to the context at the end of the event, that is, that x has a coolness that is below the standard of comparison for that context at the beginning of the event, and above it at the end. But this merely requires an increase in coolness (which amounts to a decrease in temperature, since cool is a “polar negative” adjective; see Seuren 1978; Bierwisch 1989; Kennedy 2001), and there is no entailment that a particular endstate is reached. Assuming an arbitrary number of contextual interpretations of vague predicates, differing only in where along a gradable continuum they draw the line between the things they are true and false of, (4b) is true of any subevent of an event that it is true of. In other words, it has the “subinterval property,” and so is atelic (Bennett and Partee 1982).

Abusch’s analysis predicts that DAs in general should behave like cool, having either telic or atelic interpretations depending on whether the adjectival root is analyzed in a “positive” sense as in (4a) or a “comparative” sense as in (4b).3 One potential problem for this analysis comes from the fact that many DAs have default telic interpretations. Such verbs have atelic uses, but in the absence of explicit morphosyntactic or contextual information forcing such interpretations, they are treated as telic. This is illustrated by the examples in (5).

As observed by Kearns (2007), the most natural interpretations of examples like these are ones in which the affected objects reach the endstate named by the positive form of the adjective, as illustrated by the oddity of the completions in parentheses. These completions do not result in true contradictions, showing that the telic interpretation is not obligatory, but they do result in degraded acceptability.4 In particular, they have the feel of “garden path effects,” suggesting that the verbs in (5) have default telic positive interpretations, and the completions require reanalysis to the atelic, comparative ones. A potential explanation for this default is a pragmatic one: since the telic interpretation entails the atelic one, it is more informative and therefore stronger. In the absence of information to the contrary – which could in principle be implicit (contextual), compositional (such as modification that is consistent only with atelicity), or even lexical (word-based defaults) – the strongest meaning should be preferred, resulting in a preference for telic interpretations (cf. Dalrymple et al.’s (1998) analysis of interpretive variability

in reciprocals).

Although we will end up adopting a version of this proposal to explain the fact that verbs like those in (5) have default telic interpretations, it is not enough to save Abusch’s analysis from a more serious second problem: there are DAs which appear to have only atelic interpretations. For example, (6a–b) show that DAs derived from the dimensional adjectives wide and deep accept only durative temporal modifiers:

In addition, entailment from the progressive to the perfect is automatic, as shown by the fact that (7a–b), unlike e.g. (8a–b), are contradictory.

These facts are unexpected if a DA such as widen is ambiguous between the two meanings in (9), comparable to those for cool in (4).

In particular, if (9a) were an option, then widen should have a telic interpretation equivalent to become wide, namely “come to have a width that is at least as great as the minimum width that counts as wide in the context of utterance.”5 It would then be possible to simultaneously assert that something widens in the sense of (9b) while denying that it widens in the sense of (9a) (this is Zwicky and Sadock’s (1975) “test of contradiction”), since an object can increase in width without becoming wide. But this is not the case: if it were, then the examples in (7) would fail to generate a contradiction. That is, there would be an interpretation of, for example, (7a) in which the occurrence of widen in the perfective form is understood to mean the same as become wide, not become wider, in which case there would be no incompatibility with the progressive assertion: a gap could be increasing in width without having become wide (see note 5). We can therefore conclude that DAs like widen and deepen resist interpretations parallel to (9a), a fact that deserves explanation.6

A final problem with Abusch’s analysis involves the interpretation of measure phrases in DAs. Consider the following examples:

The measure phrases in these examples specify the amount that the respective subjects change in temperature and width as a result of participating in the event described by the verbs, and in doing so, render the predicates telic (a point to which we will return below). However, it is difficult to see how this result can be achieved given the options in (4) and (9). It might seem reasonable to modify the account so that the measure phrase and adjectival base together provide the value of the inchoative predicate, but this would predict that (10a–b) should have the meanings in (11a–b).

This prediction is obviously incorrect: cool is a gradable adjective that does not combine with measure phrases (see Schwarzschild 2005 and Svenonius and Kennedy 2006 for recent discussion of this issue), and (11b) does not accurately convey the meaning of (10b). Instead, (10a–b) are more accurately paraphrased by (12a–b).

These paraphrases show that measure phrases in DAs express “differential” amounts, just like measure phrases in comparatives: instead of specifying the total amount to which an object possesses some measurable gradable property (as in (11b), where six inches is used to describe the total/maximal width of the gap), such measure phrases convey the extent to which two objects (or the same object at different times) differ along some gradable continuum. An analysis of variable telicity in DAs that is based strictly on the vagueness of the positive form, such as Abusch’s, is not equipped to convey this kind of meaning. (See von Stechow 1984 for a discussion of the problem differential measure phrases present for a semantics of comparatives based on the analysis of vagueness in Kamp 1975 and Klein 1980, on which Abusch builds her analysis of DAs.)

1 We will focus primarily on inchoative forms of DAs in this chapter, even though most have causative variants as well, as it is the semantics of the “inchoative cor” that is crucial to capturing variable telicity. That is, telicity does not correlate with causativity: if a DA shows variable telicity at all, then it shows it in both its causative and inchoative forms (Hay et al. 1999). Since for deadjectival verbs the semantics of the latter are part of the former (on standard assumptions about causative/inchoative alternations; though see Koontz-Garboden 2007), it must be the case that it is the latter on which telicity is based.

2 Abusch does not assume an event semantics; (3b) simply restates the interval-based semantics for become that she assumes (based on Dowty 1979) in terms of an event argument; cf. Krifka (1998b); Parsons (1990).

3 Abusch’s analysis of the atelic interpretation is often characterized as involving a “comparative” semantics, and we will continue to use this label here, but with caution: this characterization is not quite accurate. Abusch’s semantics is similar to e.g. Klein’s (1980) analysis of comparatives in that it involves existential quantification over contextual interpretations of vague predicates, but it is crucially different in not introducing an explicit standard of comparison (the expression contributed by the than constituent in an English comparative construction).

4 Kearns points out that this effect is gradient, with some verbs (like darken) showing it mildly and others (like empty) showing it quite strongly. However, even verbs like empty can take on atelic interpretations when the context is rich enough or other components of the sentence force such readings, as in the case of post-verbal modification by quickly (Kearns 2007):

The sink emptied quickly (but we closed the drain before it became empty).

5 Even if the exact value of such a width is vague or unknown (or unknowable; see Williamson 1992, 1994), it remains the case that (9a) should be semantically telic, since it imposes exactly the same kind of requirement on an event that a DA like cool does in its telic sense in (4a). This is confirmed by the absence of an entailment from the progressive to the perfect for become wide, as shown by (i).

(i) The gap is becoming wide(r), but it hasn’t become wide.

Modification of become wide with an in-PP is not particularly felicitous, but this is presumably due to the vagueness of wide, and therefore not indicative of atelicity.

6 While this conclusion is justified based on the clear contrast between the examples in (7) and those in (8), we suspect that it may be possible under special circumstances and with strong contextual support to understand DAs like widen in a telic, “positive” sense comparable to (9a).

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)