Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The status of adjectives – The presence/absence of a degree variable

المؤلف:

JENNY DOETJES

المصدر:

Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse

الجزء والصفحة:

P140-C6

2025-04-20

892

The status of adjectives – The presence/absence of a degree variable

One way to account for the special status of adjectives is to assume that scalar adjectives differ from other categories because they contain a degree variable. Under this assumption, modifiers that typically combine with adjectives are modifiers that depend on the presence of a degree variable. In this view the idea that adjectives are more “gradable” than other categories is directly implemented in the lexical representation of adjectives.

In their study of the scale structure of deverbal adjectives, Kennedy and McNally (2005: 365) assume that the structure of the scale of the derived adjective is created “by mapping from a set of potentially complex events that can be ordered in an algebraic structure as proposed in, for example, Link (1983), Landman (1989), or Lasersohn (1995).” Even though the event structure of a verb is at the basis of the scale structure of the corresponding deverbal adjective, the presence of the scale is assumed to be a property of the adjective, not of the verb it is derived from. One could assume that degree expressions modifying verbs and nouns are interpreted with respect to the algebraic structures these correspond to, while modifiers of adjectives perform an operation on a scale that is part of the linguistic representation of the adjective.

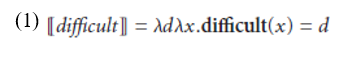

The hypothesis that adjectives should be treated as relations between individuals and degrees is often made in the literature (see Seuren 1973; Cresswell 1977; Hellan 1981; von Stechow 1984; Bierwisch 1989; Klein 1991; Kennedy and McNally 2005). An adjective such as difficult is to be seen as a relation between individuals and degrees, as in (1).1

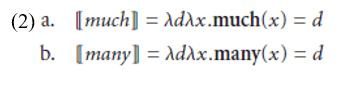

If the presence of a degree variable is typically adjectival, one has to assume that expressions such as much and many when used to modify mass nouns and plurals and very, which is used to modify an adjective, have a different semantics. Whereas very operates on the value of a degree variable, much and many should rather be seen as quantity predicates that contain a degree variable themselves (cf. Hackl 2000):2

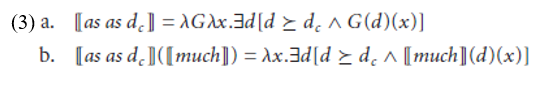

The difference between a degree expression that directly operates on a degree variable and one that makes use of a quantity predicate is illustrated in (3). The meaning of the type A expression as in (3a) has been taken from Kennedy and McNally (2005: 269) and the one of as much in (3b) is composed of as applied to the quantity predicate much.

Given (3a), application of as to a gradable adjective yields a property to a degree d which equals at least dc, the degree introduced by the as-clause. The way a degree reading is obtained by as much is very different. The quantity predicate as much would combine through intersection with another predicate. A similar analysis would hold for as many. As such, as many books denotes a set of plural objects that have the property of being books and the property of having a quantity that at least equals a contextually given degree of quantity dc.

In what follows I will discuss two consequences of this approach. In the first place, if as has a semantics as in (3a) and as much a semantics as in (3b), one might wonder what type of semantics has to be assumed for type C expressions such as more and trop, which may be used with nouns and verbs, but also with adjectives. In the second place I will consider the question of how to analyze gradable predicates that are not adjectival (e.g., gradable verbs such as to appreciate and gradable nouns such as French faim ‘hunger’). Are there reasons to assume that these expressions contain a degree variable as well? Obviously, the next question is whether one would like to claim that all categories in Table 1 contain degree variables (see Cresswell 1977).

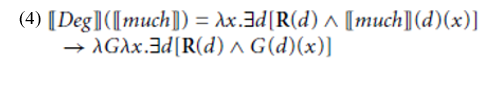

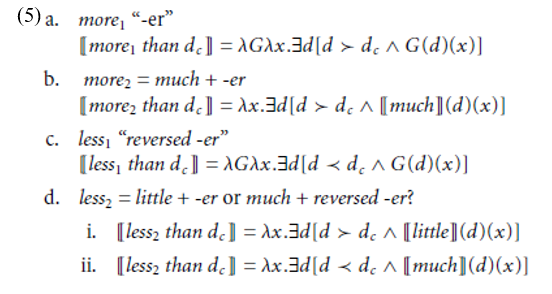

Under the assumption that adjectives contain a degree variable and other categories do not, we need two meanings for more in order to account for its ability to modify both adjectives and other categories. One of these meanings is similar to the one of as and the other to that of as much in (3). The idea that expressions that modify adjectives, but that also occur with for instance nouns, are ambiguous has been proposed in the literature by Jackendoff (1977). In order to explain that degree expressions such as as are only used with adjectives, while more can be used with other categories as well, Jackendoff assumes that more is ambiguous between a degree expression Deg (more1) and quantifier Q (more2). In what follows, I will call the two readings of more“Deg” and “Q” for ease of exposition.

Ambiguity is unproblematic if it is accidental. Once it is not, one would like to know why it exists. Some general process creating ambiguity should be at the source of any systematic ambiguity. It is clear that we are not dealing with accidental ambiguity in the case of more. As shown above, type C expressions constitute a large class, including French trop ‘too (much/many),’ moins ‘less, plus ‘more,’ un peu ‘a bit,’ English more, less, a bit, Dutch minder ‘less,’ een beetje ‘a bit,’ Portuguese muito ‘a lot, very,’ and Italian molto ‘a lot, very,’ etc. Given the generality of the phenomenon, one would like these expressions to be unambiguous, and if not, there should be a general mechanism that can account for the existence of the ambiguity.

One question is in what sense the two interpretations of more are connected. Is there a derivation of Deg towards Q or the other way around? There is historical evidence in favor of the idea that Q may be at the source of Deg. A first indication is the case of Portuguese muito. In older stages of Portuguese, muito would function as a type D expression (similar to a lot and beaucoup) and it would alternate with mui, which occurred with adjectives. The type A expression mui became obsolete and muito extended its distribution (Joao Costa, p.c.). A second indication are cases such as trop and a bit, which derive from measure constructions (meaning ‘a heap’ and ‘a bite’ respectively). Measure constructions are at first used in the nominal system. Once they have a pure degree interpretation theymay extend their distribution and become type D or type C expressions. This suggests that there is a diachronic mechanism that allows a Q to turn into a Deg by abstracting over the quantity predicate. The definition of Deg in (4) is taken from Kennedy and McNally (2005: 367), where R is a restriction on the degree argument of the adjective.

The Examples in (5) give the Deg and the Q interpretations for more and for less:

The case of more is rather simple. The basic more (more2, the Q) is built out of much + the comparative morpheme -er. In order to form more1, much is replaced by an abstraction over a gradable predicate by application of the rule in (4), and we are left with a synonym of -er. The case of less is more complicated. The Q less, less2, could have two meanings, one of which involves much, the other little. If one assumes less is a comparative of little, which is at first sight straightforward, one cannot simply abstract over little in order to get to less1 because then less1 would have the same meaning as more1 and the comparative suffix -er. This might be seen as evidence for the assumption that less is based on much, and includes a degree item with the meaning of a “reversed” -er, which is lexicalized in English by less1. This would also hold for German weniger, fromwenig + -er ‘little’ + “-er”. As weniger may be combined with adjectives (e.g. weniger klug ‘less smart’), one has to assume that alongside the compositional meaning in (5d.i) weniger can also have the equivalent meaning in (5d.ii). This in turn may undergo the rule in (4), resulting in the meaning of “reversed -er.”

In any case, the formation of less1 , whichwould be derived fromthe representation of less2 in (5d.i) by an abstraction rule along the lines of (4), and which would have the same meaning as more1, has to be blocked. As Chris Kennedy has pointed out to me, the abstraction rule in (4) might be blocked by the presence of little. Given that little, being the antonym of much, can be seen as a negative quantity predicate, that is, a predicate that gives information about the quantity an object does not have, it seems reasonable to assume that only the positive quantity predicate may be abstracted over by a rule such as (4).

The derivation of less1 shows that in order to derive it we need an abstract operator with the meaning of less1, that is, less2 cannot be seen as a suppletive form of two morphemes that independently exist in the language: this would be true for more and for the first definition of less2, but not for the second one, which is the one we need in order to derive less1. Note that the quantity predicate in for instance French trop ‘too much’ does not correspond to a lexical item either, given that beaucoup, the French counterpart of much/many, may not be modified by degree expressions, as illustrated by the ungrammaticality of ∗très beaucoup ‘very much.’ The same is true for Spanish mucho ‘much,’ as illustrated by the impossibility of ∗muy mucho ‘very much.’ The absence of a lexical quantity predicate seems to correlate with the wealth of type C expressions in these languages.

The case of less in English (and its counterparts weniger and minder in German and Dutch) is quite interesting, because in Germanic languages there is a strong tendency to lexicalize type A expressions separately, and to construe type C expressions by combining a type A expression and much. As such, if less is considered to be a combination of reversed -er and a quantity predicate (abstract much) as in (5d.ii), the non-existence of a separately lexicalized type A expression with the meaning of a reversed -er is intriguing.

The ambiguity of type C expressions might also have consequences for their syntax, given the claim that type A are syntactic heads while type C expressions are adjuncts (Doetjes 1997; Neeleman et al. 2004). If these syntactic differences are related to the semantic differences between the two types of expressions, one expects type C expressions to have a different syntax depending on whether they combine with an adjective or not.

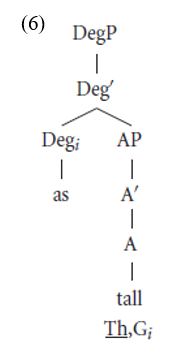

The idea that type A expressions are syntactic heads of a Degree phrase was first put forward by Corver (1990) and Zwarts (1992). Zwarts explicitly argues that the projection of a degree phrase hosting a type A expression in its head is related to the semantic representation of the adjective, which contains a degree variable. The structure proposed by Zwarts (1992: 32) is given in (6), where The corresponds to the variable x and Gi to the variable d in (3a).

Type C expressions, on the other hand, have been claimed to be adjuncts rather than heads. Doetjes (1997) and Neeleman et al. (2004) argue that expressions such as as much are adjuncts, rather than heads, and that this is why they are not sensitive to the categorial properties of the expression they modify. Type A expressions are heads and as such categorially select an AP, while type C expressions are adjoined to an XP of any category, provided that this category is semantically compatible with the scalar interpretation of the degree expression.

Given the hypothesis that degree variables are typically adjectival, the syntactic difference between degree expressions involving a quantity predicate (type C) and the ones that directly operate on the meaning of an adjective (type A) might be related to the different type of semantic operation that is needed in order to interpret them (Chris Kennedy, p.c.). From a semantic point of view, as combines with an adjective through function application, while as much is a quantity predicate, and combines with another predicate through intersection (see 3). It is not implausible that this semantic difference corresponds to head versus adjunct syntax. Moreover, it would allow us to do away with the idea of categorial selection, and view the facts as an instance of semantic selection after all. If this idea is adopted, it implies that the ambiguity issue discussed above also concerns the syntactic position the degree expression occupies. That is, less1 and more1 would occupy a head position when used with a gradable adjective, and an adjunct position elsewhere. This in turn predicts that a type C expression used with a gradable adjective syntactically should behave like a type A expression. However, a closer look at the data motivating the difference in syntactic status of type A and type C expressions shows that this prediction is not borne out.

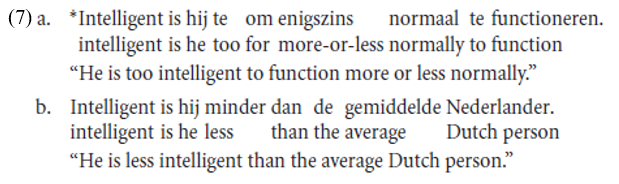

Neeleman et al. show that there are a number of differences between type A and type C expressions (their class-1 and class-2) all of which obtain in the context of adjectives.3 For instance, adjectives may be stranded in the context of a type C expression, but not in the context of a type A expression:

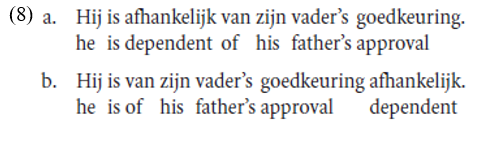

A second case of different syntactic behavior of type A and type C expressions concerns the various positions the complement of an adjective may occupy in Dutch. As the example in (8) shows, the complement of an adjective in Dutch may scramble to a position to the left of this adjective (see also Corver, 1997):

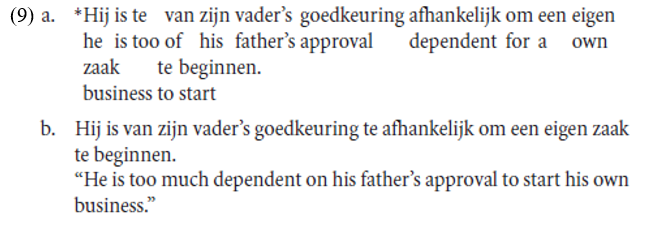

As shown in (9), the presence of a type A expression blocks scrambling to a position in between the degree modifier and the adjective, while scrambling to a position to the left of the degree expression is possible:

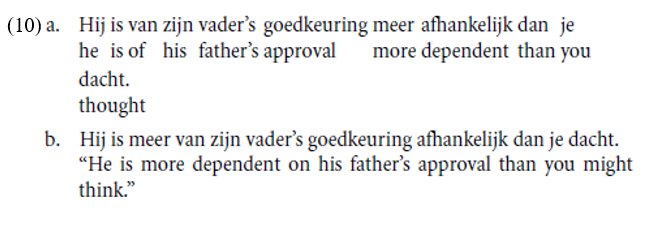

Neeleman et al. argue that the ungrammaticality of (9) is due to an adjacency requirement of the head Deg and the head of its complement. Interestingly, type C expressions such as more do not impose this requirement:

For Neeleman et al., the contrast between (9) and (10) corroborates their claim that meer ‘more’ (type C, their class-2) is an adjunct, while te ‘too’ (type A, their class-1) is a head. Unlike the relation between an adjunct and a following adjective, the head–complement relation between a Deg and an adjective is blocked by an intervening scrambled complement of the adjective. This is in accordance with their claim that the only difference between too and too much is syntactic: too is claimed to categorially select an adjective and the insertion of much is seen as insertion of a dummy that is necessarily present in order to make too syntactically compatible with categories other than adjectives.4

Under the ambiguity approach sketched above, and assuming the appealing hypothesis that the semantic difference between modifiers of adjectives and modifiers of other categories is reflected in syntactic structure, the contrasts in (7) and (8)–(10) are not expected to exist. The syntactic differences between type A and type C expressions seem to be independent of whether the type C expression combines with an adjective or with another category. If they are due to a head/adjunct contrast, as argued by Neeleman et al., this contrast does not seem to be a reflection of the two different semantic structures illustrated in (3).

Up to this point it has been assumed that the semantics of type A expressions makes them sensitive to the presence of a degree variable, and that this is why they combine with adjectives rather than with other categories. The second most restricted type of degree expression at the top of the continuum in Table 1 is type B, which is not restricted to adjectives, as it is also compatible with gradable expressions of other categories.

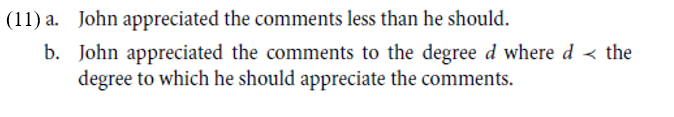

As shown in (11), verbs such as to appreciate do not seem to have a quantity interpretation:

The possibility of having a degree interpretation and not a quantity interpretation in the case of modification of the verb to appreciate indicates that postulation of a quantity predicate as in (3b) is not enough to explain all the uses of degree modifiers outside of the adjectival domain. The facts can have two explanations: either there has to be a mechanism that modifies the degree of appreciation in (11a) and that does not make use of a degree variable, or all expressions modified by a type B expression contain a degree variable. If the latter explanation is correct, the idea that the availability of a degree variable alone is what determines the distribution of Type A expressions must be wrong. If, on the other hand, another mechanism is involved in determining the degree of appreciation in (11a), one may wonder why type A expressions do not make use of this mechanism. It is clear that in order to maintain the hypothesis that only adjectives contain degree variables, independent evidence in favor of a linguistic difference between gradable adjectives on the one hand and the other gradable predicates in Table 1 on the other is necessary.5

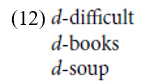

So far we have considered limiting degree variables to the contexts where either type A or type B expressions are found. A third obvious possibility is to assume that degree variables are found in the context of type C expressions, that is, for all categories in Table1. On such an approach, all degree expressions have similar meanings.6 This view is not new either. Cresswell (1977) and von Stechow (1984) argue in favor of such an analysis, in particular with respect to mass nouns. On this view, lexical items such as more and trop are not ambiguous, and have a meaning similar to that of type A expressions. All degree expressions act on a degree variable, but this variable corresponds to a qualitative scale in the case of adjectives such as difficult, and to a quantitative scale in the case of nouns. The adjective difficult and the nouns books and soup would then all have a degree variable, as in (12):

Cresswell illustrates this approach with the example in (13) for the noun water, which is analyzed as a two-place predicate, such that x is an amount of water with volume y. The sentence in (13a) gets the interpretation in (13b):

The interpretation in (13b) could also be paraphrased as: the quantity of ebbing water exceeds the quantity of flowing mud, where quantity is expressed as a degree on a scale. I will not attempt to provide a full analysis along these lines here. Note that both Cresswell and von Stechow only talk about mass nouns. More in combination with a mass noun has the same semantics as more modifying an adjective. Given the much larger distribution of more, it seems plausible that this idea should be extended to other contexts where more is found. An advantage of such an approach is the uniform semantics that can be adopted for degree expressions. However, within this type of approach the presence or absence of a degree variable is totally independent of the distribution of degree expressions, and we are left without an answer to the question of why adjectives are at one end of the degree expression continuum.

1 I will not consider an alternative analysis in which the scalar adjective is seen as a partially ordered set of individuals. In such an approach scalar and non-scalar adjectives have the same representation; the difference between the two is the presence versus absence of a partial ordering of the domain. This type of approach has been advocated by Klein (1980). For arguments against such a view, see Kennedy (1999a, b).

2 I define much and many in the same way as the scalar adjective difficult in (1), that is, as a predicate. For ease of exposition, I will disregard the differences between predicative adjectives on the one hand and attributive adjectives and adverbs derived from adjectives on the other.

3 Neeleman et al. also discuss the possibility of topicalization of a type C expression in the context of an adjective. As predicted, type A expressions, being heads, may not undergo topicalization. Even though topicalization of a type C expression is certainly not as bad as topicalization of a type A expression, it is not straightforwardly possible in any given sentence (see Neeleman et al. 2004 for examples). As similar problems occur with topicalization of a degree expression modifying a noun, there is no contrast between an adjectival and a non-adjectival context.

4 Note that in certain approaches to categorial selection, semantic properties of the category trigger this selection. Zwarts (1992) tries to connect the syntactic structure in (4), in which the Deg selects an adjectival projection, to semantic properties of adjectives (the presence of a degree variable). In Doetjes (1997) and Neeleman et al. (2004) we rather assume that categorial selection of adjectives is a purely formal issue. Under this assumption, the main question addressed in this chapter might be formulated as follows: Why do degree expressions categorially select adjectives rather than some other gradable category, e.g. gradable verbs or gradable nominal predicates? In this chapter I explore semantic properties of adjectives that may be related to the distribution of type A expressions, rather than develop an argument either for or against the existence of categorial selection.

5 Such evidence might come from restrictions on the use of antonyms in comparatives. See Kennedy (1999a, b), who argues on the basis of the distribution of antonymous adjectives in comparatives that the semantics of gradable adjectives needs to make reference to degrees. I will leave this issue for further research.

6 Cf. Doetjes (1997) and Neeleman et al. (2004). Bresnan (1973) argues that degree modifiers always have the form Deg + much, and may apply to adjectives, nouns, and verbs alike. In the context of an adjective, however, much is deleted. Given the discussion at the beginning of this section, it is quite appealing to see this deletion of much as an instance of rule (4), which would imply that her proposal is actually very close to the one in Jackendoff (1977) and very different from the type of analysis advocated by Cresswell.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)