Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The status of adjectives – Adjectival scales

المؤلف:

JENNY DOETJES

المصدر:

Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse

الجزء والصفحة:

P149-C6

2025-04-21

797

The status of adjectives – Adjectival scales

The last idea that will be explored with respect to the special properties of adjectives is that adjectives are associated with certain types of scales while degree modifiers may be sensitive to properties of scales. Kennedy and McNally (2005) argue that this type of analysis explains the distribution of degree expressions in the adjectival domain, specifically, the distribution of much and very. Whereas the meaning of much makes reference to a lower closed scale, very is defined with respect to a relative standard.

Kennedy and McNally’s proposal can be made more general. It might be hypothesized that certain scale types are typically adjectival, and that degree expressions that are sensitive to them are for that reason restricted to the adjectival system. On this view, adjectives differ from other categories in terms of the type of scales they are associated with. One might argue then that adjectives are more “gradable” than other categories in the sense that they are compatible with a wider array of scales. Expressions that select “typical” adjectival scales are the ones that are only found for (a subset of) adjectives and not for other categories. A further consequence of such an approach is that we predict that there are two types of adjectives: the ones that have typically adjectival scales and therefore combine only with expressions that cannot be used outside of the adjectival system (e.g. very) and those that have more common scales, which makes them compatible with expressions that are also used outside of the adjectival system (this would be the case of the adjectives introducing a lower bound and combining with much).

Let us first have a closer look at the work of Kennedy and McNally (2005) in order to gain a better understanding of the differences between types of scales. As already said above, the types that are relevant with respect to the distribution of much as opposed to very are the lower closed scale pattern and the scales that are characterized by a relative standard.

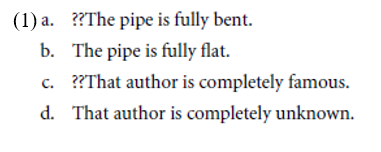

The test for a lower (but not fully) closed scale pattern is illustrated in (1). Expressions that have a lower closed scale are themselves incompatible with expressions such as completely and fully that need an upper closed scale. However, given their lower bound, their antonyms will have upper closed scales, and as such the antonyms will be compatible with completely and fully.

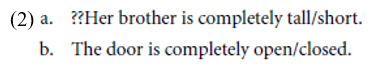

Given the data in (1) one may conclude that the adjectives bent and famous have lower closed scales, while their antonyms flat and unknown have upper closed scales. Antonyms of adjectives introducing fully open or fully closed scales are parallel to one another. Either both antonyms are incompatible with completely (open scale) or both are compatible with completely (fully closed scale). This is illustrated in (2) for the open scale adjectives tall and short and the closed scale adjectives open and closed:

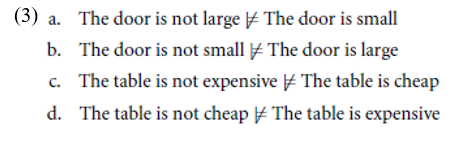

The second aspect of scale structure that enters into play is the presence of a standard of comparison. This notion can be illustrated on the basis of an adjective with a relative standard, such as tall. Being tall means being tall to a degree d that exceeds a contextually defined degree, corresponding to what is expected in the given context (this usually involves formation of a comparison class, Klein 1980). The contextually defined degree of tallness that has to be taken into account in order to judge a sentence with tall is the standard of comparison. The presence of a relative standard can be tested by means of negation. Some examples are given in (3).

If a table is not cheap, it means that its cost is not lower than expected in a given context. This does not imply that its cost is higher than expected or expensive.

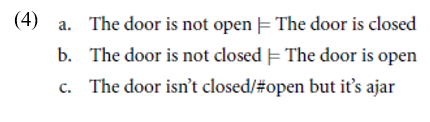

The standard of comparison is not always relative (context-dependent) as in the examples in (3). It may also be absolute (cf. Yoon 1996 and Rotstein and Winter 2004, who call adjectives with an absolute standard “total adjectives” as opposed to “partial adjectives,” which have a relative standard). Absolute standards may be maximal or minimal. A maximal standard corresponds to the upper bound of an upper or fully closed scale. A minimal standard corresponds to the lower bound of a lower or fully closed scale. The presence of an absolute standard may be tested by making use of negation as well: the negation of an adjective with an absolute standard entails its antonym. This is illustrated in (4) for the antonyms open and closed. Recall that both are fully closed scale adjectives (cf. 2b above). The absolute standard is minimal in the case of open, and maximal in the case of closed. This is illustrated by (4c). Even if a door is minimally open, it is open. On the other hand, a door needs to be maximally closed in order to be closed.

Kennedy and McNally argue that very boosts the value of a relative standard. The relative standard for tall, for instance, is computed on the basis of the expected length. A tall person is taller than the average in a given context. By using very tall rather than tall the comparison class changes. Not all contextually relevant persons are taken into account but only those that are tall. As a result, a very tall person is someone who is tall as compared to other tall persons, while a tall person is tall with respect to other persons that may be tall or short or something in between (see also Klein 1980). The degree modifier much indicates a high degree on the basis of a lower bound, and is therefore incompatible with open scale adjectives.1

Given the analysis of very, it is important to know under what conditions a relative standard may be present. Kennedy and McNally argue that gradable adjectives associated with totally open scales always have relative standards. Totally or partially closed scales usually have absolute standards, but they may have relative standards as well in certain contexts, as illustrated in (5b) for the closed scale adjective full.

The presence of a relative standard for comparison seems to be disfavored when there is already an absolute standard that corresponds to the minimal or maximal value on a partially or fully closed scale. As open scales lack a minimum or a maximum value that may be mapped onto an absolute standard, these scales are condemned to having relative standards. This accounts for the fact that relative standards are relatively rare and strongly context-dependent in the case of (partially) closed scale adjectives.2

Let us now turn to the idea that certain types of scales are restricted to adjectives, and as such restrict the distribution of certain degree expressions to the adjectival domain. More in particular, I would like to postulate that open scales, as well as relative standards, are typically adjectival, while lower closed scales are found both in the adjectival domain and outside of it. Consider for instance the data in (6). When negation is applied to a noun or an eventive verb, there is a “zero” reading, typical for a lower closed scale.3

According to (6a), John read zero books, and similarly, there is “zero” reading by John in (6b). In the case of abstract verbs such as to appreciate a zero point seems to be available as well. As it is hard to determine what antonym to use, I will use a slightly modified form of the test, making use of the absence of the relative standard in comparatives. This form of the test can be illustrated for tall in (7a) and for to appreciate in (7b):

The example in (7a) is clearly not contradictory at all, while the example in (7b) is strange.

In the remainder of this section, I would like to briefly discuss two questions that are relevant for the hypothesis that certain types of scales are typically adjectival. The first is what happens after conversion from one category to another. The second question is whether it is possible to account for the distribution of all type A expressions in this way.

There is some evidence that a noun, when turned into an adjective, switches from a lower closed scale to an open scale with a relative standard. This is illustrated by the examples in (8) for the Dutch pair geduld ‘patience’ and geduldig ‘patient.’ The adjective geduldig is derived from the noun geduld by suffixation of -ig.

The sentence in (8a) is a contradiction. If Jan has no patience, he cannot possibly have more of it than Piet. If he is not patient, however, it does not mean that he has no patience at all, it just means that he is less patient than most people. This is corroborated by the intuition that the degree of Jan’s impatience is greater for Jan heeft geen geduld than for Jan is niet geduldig. These data suggest that in fact the type of scale changes with the change of category. I will leave this issue for further research, but the data in (8) indicate that category and scalar properties do in fact interact.

As for the second question, if the distribution of very is determined by its interpretation (it boosts a relative standard), one would like to know what happens to the type A expression as, which is not sensitive to the presence of a relative standard. It seems that as is in fact more easily compatible with adjectives such as needed and praised, even though as needed/praised and as much needed/praised are both available. This suggests that as is in fact sensitive to the class of adjectives as a whole, while much and as much are sensitive to the presence of a lower bound.

The discussion in this section shows that the idea of using scale structure in order to better understand the distribution of degree expressions on the one hand and the status of adjectives as opposed to other categories on the other, is promising, even though more research is needed in order to make it possible to use this for explaining the distribution of all type A expressions. However, it seems to be true that only a subclass of the types of scales found for adjectives is found for other categories as well. This is in particular clear for mass nouns, plurals, and eventive verbs. The scalar properties of nominal and verbal gradable predicates (faim ‘hunger’ and to appreciate) constitute an issue for further research, and this issue is connected to the question of whether one would like to assume a degree variable in their representation or not.

1 A reviewer wonders why it is not possible to use much open, as open introduces a lower bound. It should be noted that open also introduces an upper bound, given that a door can be completely open, and this seems to be the reason why much open is excluded. The only way to get a high degree interpretation for an upper closed adjective seems to be insertion of a relative standard, as illustrated for full in (46).

2 Neeleman et al. (2004) argue that the application of the rules introducing the equivalent of a relative standard is forced by the fact that without applying them the sentence is usually a truism. A sentence such as John is tall would mean that John has height, which is already presupposed by the use of the adjective tall.

3 See also the discussion on the mapping of event structure to scale structure in Kennedy and McNally (2005: 361–365). They argue that in all cases this mapping yields lower closed scales.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)