تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

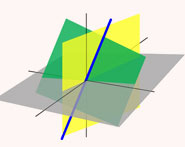

الهندسة

الهندسة

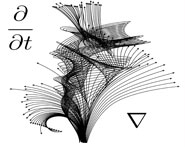

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 12-10-2017

Date: 9-11-2017

Date: 9-11-2017

|

Died: 1986 in Devlali, India

D R Kaprekar was born in Dahanu, a town on the west coast of India about 100 km north of Mumbai. He was brought up by his father after his mother died when he was eight years old. His father was a clerk who was fascinated by astrology. Although astrology requires no deep mathematics, it does require a considerable ability to calculate with numbers, and Kaprekar's father certainly gave his son a love of calculating.

Kaprekar attended secondary school in Thane (sometime written Thana), which is northeast of Mumbai but so close that it is essentially a suburb. There, as he had from the time he was young, he spent many happy hours solving mathematical puzzles. He began his tertiary studies at Fergusson College in Pune in 1923. There he excelled, winning the Wrangler R P Paranjpe Mathematical Prize in 1927. This prize was awarded for the best original mathematics produced by a student and it is certainly fitting that Kaprekar won this prize as he always showed great originality in the number theoretic questions he thought up. He graduated with a B.Sc. from the College in 1929 and in the same year he was appointed as a school teacher of mathematics in Devlali, a town very close to Nashik which is about 100 km due east of Dahanu, the town of his birth. He spent his whole career teaching in Devlali until he retired at the age of 58 in 1962.

The fascination for numbers which Kaprekar had as a child continued throughout his life. He was a good school teacher, using his own love of numbers to motivate his pupils, and was often invited to speak at local colleges about his unique methods. He realised that he was addicted to number theory and he would say of himself:-

A drunkard wants to go on drinking wine to remain in that pleasurable state. The same is the case with me in so far as numbers are concerned.

Many Indian mathematicians laughed at Kaprekar's number theoretic ideas thinking them to be trivial and unimportant. He did manage to publish some of his ideas in low level mathematics journals, but other papers were privately published as pamphlets with inscriptions such as Privately printed, Devlali orPublished by the author, Khareswada, Devlali, India. Kaprekar's name today is well-known and many mathematicians have found themselves intrigued by the ideas about numbers which Kaprekar found so addictive. Let us look at some of the ideas which he introduced.

Perhaps the best known of Kaprekar's results is the following which relates to the number 6174, today called Kaprekar's constant. One starts with any four-digit number, not all the digits being equal. Suppose we choose 4637 (which is the first four digits of EFR's telephone number!). Rearrange the digits to form the largest and smallest numbers with these digits, namely 7643 and 3467, and subtract the smaller from the larger to obtain 4167. Continue the process with this number - subtract 1467 from 7641 and we obtain 6174, Kaprekar's constant. Lets try again. Choose 3743 (which is the last four digits of EFR's telephone number!).

7433 - 3347 = 4086

8640 - 0468 = 8172

8721 - 1278 = 7443

7443 - 3447 = 3996

9963 - 3699 = 6264

6642 - 2466 = 4176

7641 - 1467 = 6174

Again we have obtained Kaprekar's constant. In fact applying Kaprekar's process to almost any four-digit number will result in 6174 after at most 7 steps (so our last example was one where the process has maximal length). This was first discovered by Kaprekar in 1946 and he announced it at the Madras Mathematical Conference in 1949. He published the result in the paper Problems involving reversal of digits in Scripta Mathematica in 1953. Clearly starting with 1111 will yield 0 from Kaprekar's process. In fact the Kaprekar process will yield either 0 or 6174. Exactly 77 four digit numbers stabilize to 0 under the Kaprekar process, the remainder will stabilize to 6174. Anyone interested could experiment with numbers with more than 4 digits and see if they stabilise to a single number (other than 0).

What about other properties of digits which Kaprekar investigated? A Kaprekar number n is such that n2 can be split into two so that the two parts sum to n. For example 7032 = 494209. But 494 + 209 = 703. Notice that when the square is split we can start the right-hand most part with 0s. For example 99992= 99980001. But 9998 + 0001 = 9999. Of course from this observation we see that there are infinitely many Kaprekar numbers (certainly 9, 99, 999, 9999, ... are all Kaprekar numbers). The first few Kaprekar numbers are:

1, 9, 45, 55, 99, 297, 703, 999, 2223, 2728, 4879, 4950, 5050, 5292, 7272, 7777, 9999, 17344, 22222, 38962, 77778, 82656, 95121, 99999, 142857, 148149, 181819, 187110, 208495, ...

It was shown in 2000 that Kaprekar numbers are in one-one correspondence with the unitary divisors of 10n - 1 (x is a unitary divisor of z if z = xy where x and y are coprime). Of course we have looked at Kaprekar numbers to base 10. The same concept is equally interesting for other bases. A paper by Kaprekar describing properties of these numbers is [3].

Next we describe Kaprekar's 'self-numbers' or 'Swayambhu' (see [5]). First we need to describe what Kaprekar called 'Digitadition'. Start with a number, say 23. The sum of its digits are 5 which we add to 23 to obtain 28. Again add 2 and 8 to get 10 which we add to 28 to get 38. Continuing gives the sequence

23, 28, 38, 49, 62, 70, ...

These are all generated by 23. But is 23 generated by a smaller number? Yes, 16 generates 23. In fact the sequence we looked at really starts at 1

1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 23, 28, 38, 49, 62, 70, ...

Try starting with 29. Then we get

29, 40, 44, 52, 59, 73, ...

But 29 is generated by 19, which in turn is generated by 14, which is generated by 7. However, nothing generates 7 - it is a self-number. The self-numbers are

1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 20, 31, 42, 53, 64, 75, 86, 97, 108, 110, 121, 132, 143, 154, 165, 176, 187, 198, 209, 211, 222, 233, 244, 255, 266, 277, 288, 299, 310, 312, 323, 334, 345, ...

Now Kaprekar makes other remarks about self-numbers in [5]. For example he notes that certain numbers are generated by more than a single number - these he calls junction numbers. He points outs that 101 is a junction number since it is generated by 100 and by 91. He remarks that numbers exist with more than 2 generators. The possible digitadition series are separated into three types: type A has all is members coprime to 3; type B has all is members divisible by 3 but not by 9; C has all is members divisible by 9. Kaprekar notes that if x and y are of the same type (that is, each prime to 3, or each divisible by 3 but not 9, or each divisible by 9) then their digitadition series coincide after a certain point. He conjectured that a digitadition series cannot contain more than 4 consecutive primes.

References [4] and [6] look at 'Demlo numbers'. We will not give the definition of these numbers but we note that the name comes from the station where he was changing trains on the Bombay to Thane line in 1923 when he had the idea to study numbers of that type.

For the final type of numbers which we will consider that were examined by Kaprekar we look at Harshad numbers (from the Sanskrit meaning "great joy"). These are numbers divisible by the sum of their digits. So 1, 2, ..., 9 must be Harshad numbers, and the next ones are

10, 12, 18, 20, 21, 24, 27, 30, 36, 40, 42, 45, 48, 50, 54, 60, 63, 70, 72, 80, 81, 84, 90, 100, 102, 108, 110, 111, 112, 114, 117, 120, 126, 132, 133, 135, 140, 144, 150, 152, 153, 156, 162, 171, 180, 190, 192, 195, 198, 200, ...

It will be noticed that 80, 81 are a pair of consecutive numbers which are both Harshad, while 110, 111, 112 are three consecutive numbers all Harshad. It was proved in 1994 that no 21 consecutive numbers can all be Harshad numbers. It is possible to have 20 consecutive Harshad numbers but one has to go to numbers greater than 1044363342786 before such a sequence is found. One further intriguing property is that 2!, 3!, 4!, 5!, ... are all Harshad numbers. One would be tempted to conjecture that n! is a Harshad number for every n - this however would be incorrect. The smallest factorial which is not a Harshad number is 432!.

The self-numbers which are also Harshad numbers are:

1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 20, 42, 108, 110, 132, 198, 209, 222, 266, 288, 312, 378, 400, 468, 512, 558, 648, 738, 782, 804, 828, 918, 1032, 1098, 1122, 1188, 1212, 1278, 1300, 1368, 1458, 1526, 1548, 1638, 1704, 1728, 1818, 1974, 2007, 2022, 2088, 2112, 2156, 2178, ...

Note that 2007 (the year in which this article was written) is both a self-numbers and a Harshad number.

Harshad numbers for bases other than 10 are also interesting and we can ask whether any number is a Harshad number for every base. The are only four such numbers 1, 2, 4, and 6.

We have taken quite a while to look at a selection of different properties of numbers investigated by Kaprekar. Let us finally give a few more biographical details. We explained above that he retired at the age of 58 in 1962. Sadly his wife died in 1966 and after this he found that his pension was insufficient to allow him to live. One has to understand that this was despite the fact that Kaprekar lived in the cheapest possible way, being only interested in spending his waking hours experimenting with numbers. He was forced to give private tuition in mathematics and science to make enough money to survive.

We have seen how Kaprekar invented different number properties throughout his life. He was not well known, however, despite many of his papers being reviewed in Mathematical Reviews. International fame only came in 1975 when Martin Gardener wrote about Kaprekar and his numbers in his 'Mathematical Games' column in the March issue of Scientific American.

Articles:

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اتحاد كليات الطب الملكية البريطانية يشيد بالمستوى العلمي لطلبة جامعة العميد وبيئتها التعليمية

|

|

|