تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

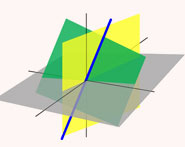

الهندسة

الهندسة

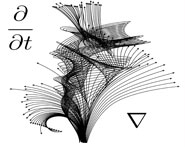

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 24-1-2017

Date: 31-1-2017

Date: 5-2-2017

|

Died: 3 March 1879 in Madeira Islands, Portugal

William Clifford showed great promise at school where he won prizes in many different subjects. At age 15 he was sent to King's College, London where he excelled in mathematics and also in classics, English literature and (perhaps unexpectedly) in gymnastics.

When he was 18 years old William entered Trinity College, Cambridge. He won not only prizes for mathematics but also a prize for a speech he delivered on Sir Walter Raleigh. He was second wrangler in his final examinations (in common with many other famous mathematicians who were second at Cambridge like Thomson and Maxwell). He was elected to a Fellowship at Trinity in 1868.

In 1870 he was part of an expedition to Italy to obtain scientific data from an eclipse. He had the unfortunate experience of being shipwrecked near Sicily, but he was fortunate to survive.

In 1871 Clifford was appointed to the chair of Mathematics and Mechanics at University College London. In 1874 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. He was also an enthusiastic member of the London Mathematical Society which held its meetings at University College.

Influenced by the work of Riemann and Lobachevsky, Clifford studied non-euclidean geometry. In 1870 he wrote On the space theory of matter in which he argued that energy and matter are simply different types of curvature of space. In this work he presents ideas which were to form a fundamental role in Einstein's general theory of relativity.

Clifford generalised the quaternions (introduced by Hamilton two years before Clifford's birth) to what he called the biquaternions and he used them to study motion in non-euclidean spaces and on certain surfaces. These are now known as 'Clifford-Klein spaces'. He showed that spaces of constant curvature could have several different topological structures.

Clifford also proved that a Riemann surface is topologically equivalent to a box with holes in it.

As a teacher Clifford's reputation was outstanding. A student, having problems with Ivory's theorem on the attraction of an ellipsoid, describes Clifford's response to his questions:-

Without any diagram or symbolic aid he described the geometrical conditions on which the solution depended, and they seemed to stand out visibly in space. There were no longer consequences to be deduced, but real and evident facts which only required to be seen.

Not only was Clifford a highly original teacher and researcher, he was also a philosopher of science. He coined the phrase 'mind-stuff' for the elements from which conscience is composed. His philosophy was further developed by Karl Pearson. In an address he gave as an undergraduate he said:-

Thought is powerless, except it make something outside of itself: the thought which conquers the world is not contemplative but active.

At the age of 23 he delivered a lecture to the Royal Institution entitled Some of the conditions of mental development. In it he tried to explain how scientific discovery comes about:-

There is no scientific discoverer, no poet, no painter, no musician, who will not tell you that he found ready made his discovery or poem or picture - that it came to him from outside, and that he did not consciously create it from within.

Macfarlane [5] tells us that:-

he was eccentric in appearance, habits and opinions.

A description of him by a fellow undergraduate is interesting:-

His neatness and dexterity were unusually great, but the most remarkable thing was his great strength as compared with his weight, as shown in some exercises. At one time he would pull up on the bar with either hand, which is well known to be one of the greatest feats of strength.

He shared with Charles Dodgson the pleasure of entertaining children. Although he never rivalled Dodgson's Lewis Carroll books in success, Clifford wrote The Little People, a collection of fairy stories written to amuse children.

In 1876 Clifford suffered a physical collapse. This was certainly made worse by overwork if not completely caused by it. He would spend the day with teaching and administrative duties, then spend all night at his research. Six months spent in Algeria and Spain allowed him to recover sufficiently to resume his duties for 18 months but, perhaps inevitably, he again collapsed. A period spent in Mediterranean countries did little for his health and after a couple of months back in England in late 1878 he left for Madeira. The hoped-for recovery never materialised and he died a few months later.

The title page of his collected works contains the quote first made by Newton speaking of Cotes

If he had lived we might have known something.

Most of his work was in fact published after his death. Volume 1 of the two volume work Elements of dynamics was published in 1878, the second volume appearing after his death. Lectures and essays and Seeing and thinking were published in 1879. Common sense of the exact sciences was completed by Pearson and published in 1885.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي ينظّم ندوة حوارية حول مفهوم العولمة الرقمية في بابل

|

|

|