تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

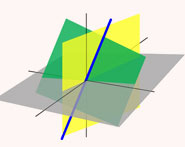

الهندسة

الهندسة

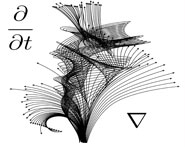

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 7-2-2017

Date: 22-1-2017

Date: 26-1-2017

|

Died: 20 September 1930 in Bad Homburg, Germany

Moritz Pasch's father was Simon Pasch who came from Rawitsch in the province of Posen. Simon was a businessman who married Rosalie Isaac from Birnbaum, Posen, in Breslau on 29 July 1841. Simon was 24 years old when he married and Rosalie was 30 years old.

Pasch attended the Elisabeth Gymnasium in Breslau, graduating in 1860. He then entered the University of Breslau with the intention of studying chemistry but soon changed topic to study for a degree in mathematics. At university he became close friends with another outstanding student of mathematics, Jakob Rosanes. He was taught by some excellent lecturers such as Heinrich Schröter, Ferdinand Joachimsthal, Rudolf Lipschitz, O E Meyer, and Paul Bachmann. Pasch was awarded his doctorate on 21 August 1865 for his thesis De duarum sectionem conicarum in circulos projectione. His thesis advisor was Schröter and Pasch dedicated his thesis to him and to Kambly his mathematics teacher at the Gymnasium.

After the award of his doctorate, together with his friend Rosanes, he went to study at the University of Berlin. There he studied under Weierstrass and Kronecker. Pasch's father died in Breslau on 24 October 1866 and he gave up his research towards his habilitation in order to help care for his family. However he was able to return to work on his habilitation thesis Zur Theorie der Komplexe und Kongruenzen von Geraden which he submitted to the Justus-Liebig University of Giessen on 29 November 1870. In August 1873 he was promoted to extraordinary professor, then two years later he was made an ordinary professor after turning down an offer of a similar post at the University of Breslau.

Pasch married Laura Reichenbach from Breslau on 15 September 1875, three weeks after being made a full professor. The marriage took place in Breslau and they had two daughters, Toni born on 18 July 1878 and Gertrud born on 16 February 1882. Both were born in Giessen.

In addition to remarkable research contributions which we mention below, Pasch was interested in the administration of the university and he devoted considerable effort as chairman of the committee responsible for the examination of prospective high school teachers. He was dean of the Philosophical Faculty at Giessen during the academic year 1885-6 and rector of the university during 1893-4. He retired on 1 April 1911, having been thesis advisor to around 30 doctoral students, wishing to devote more time to his research. He continued to be active in research and published many papers when around the age of 80. Some papers he published during the 1920s are: Der Ursprung des Zahlbegriffs (1921); Über zentrische Kollineation (1923); Betrachtungen zur Begründung der Mathematik (1924); Die natürliche Geometrie (1924); and Betrachtungen zur Begründung der Mathematik (1926).

He worked on the foundations of geometry. E W Ellers writes:-

Pasch was very concerned with the correctness of thinking which he considered equivalent to the presentation in a precise language. He was mainly concerned with the axiomatic development of mathematics. His main interests were the foundations of projective geometry and of analysis. He was devoted to what he called delicate (heikle) mathematics, as opposed to coarse (derbe) mathematics which is being practiced by many mathematicians. The results of his efforts have been expressed in his books Vorlesungen über neuere Geometrie [Teubner, Leipzig, 1882], Einleitung in die Differential- und Integralrechnung [Teubner, Leipzig, 1882], and Grundlagen der Analysis [Teubner, Leipzig, 1908].

The first of these three books is described in [2] as:-

... a watershed in the development of the foundations of geometry. Drawing on the work of his predecessors, Pasch was the first to explicitly state all the basic concepts and axioms necessary for his construction of projective geometry.

He found a number of assumptions in Euclid that nobody had noticed before [1]:-

Pasch's analysis relating to the order of points on a line and in the plane is both striking and pertinent to its understanding. Every student can draw diagrams and see that if a point B is between A and a point C, then C is not between A and B, or that every line divides a plane into two parts. But no one before Pasch had laid a basis for dealing logically with such observations. These matters may have been considered too obvious; but the result of such neglect is the need to refer constantly to intuition, so that the logical status of what is being done cannot become clear.

Pasch's Axiom is that if a line enters a triangle ABC through the side AB and does not pass through C then it must leave the triangle either between B and C or between C and A. Pasch argued in Vorlesungen über neuere Geometrie (1882) that geometers rely too heavily on physical intuition. In his view an argument in mathematics should not depend on the physical interpretation of the terms involved but upon purely formal axioms.

Pasch claimed that the principle of duality contradicted physical intuition about points and lines, nobody believed that these terms were interchangeable. Hilbert was to be influenced by these ideas of Pasch.

The article [5] is an address given by Pasch on 2 July 1894 and in the address he spoke about his ideas on how and why mathematics should be taught. E W Ellers writes in a review:-

The educational value of mathematics lies as much in its method as in its results. The most important part of the method is deduction. Rigorous reasoning appears to be the most desirable aspect in mathematical education. Pasch explains the axiomatic method in mathematics in great detail. According to Pasch, the mathematical language is often not clear, enough. Mathematical proofs sometimes leave gaps which are very often difficult to fill. He proposes that very detailed and careful deduction should prevail in teaching of mathematics.

Pasch received a number of honours for his outstanding contributions including honorary degrees from the University of Frankfurt and from the University of Freiburg to mark his eightieth birthday.

After retiring in 1911 Pasch continued to live in Giessen. His last years were particularly sad since his wife died in 1920 and his youngest daughter Gertrud, who had married the mathematician Clemens Thaer, died a year before her father. Pasch was taking a holiday in Bad Homburg when he died.

1. A Seidenberg, Biography in Dictionary of Scientific Biography (New York 1970-1990).

http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-2830903301.html

Articles:

2. W S Contro, Von Pasch zu Hilbert, Arch. History Exact Sci. 15 (3) (1975/76), 283-295.

3. M Dehn and F Engel, Moritz Pasch, Jahresberichte der Deutschen Mathematiker vereinigung 44 (1934), 120-142.

4. H C Kennedy, The origins of modern axiomatics: Pasch to Peano, Amer. Math. Monthly 79 (1972), 133-136.

5. M Pasch, Über den Bildungswert der Mathematik, Mitt. Math. Sem. Giessen No. 146 (1980), 20-39.

6. M Pasch, Eine Selbstschilderung, Mitt. Math. Sem. Giessen No. 146 (1980), 1-19.

7. M Pasch, Schriftenverzeichnis, Mitt. Math. Sem. Giessen No. 146 (1980), 40-45.

8. G Pickert, Habilitation und Vorlesungstätigkeit von M Pasch, Mitt. Math. Sem. Giessen 146 (1980), 46-57.

9. G Pickert, Inzidenz, Anordnung und Kongruenz in Pasch's Grundlegung der Geometrie, Mitt. Math. Sem. Giessen 146 (1980), 58-81.

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اتحاد كليات الطب الملكية البريطانية يشيد بالمستوى العلمي لطلبة جامعة العميد وبيئتها التعليمية

|

|

|