تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

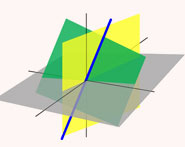

الهندسة

الهندسة

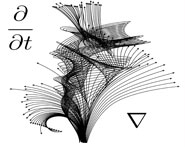

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 24-1-2016

Date: 24-1-2016

Date: 19-1-2016

|

Born: 7 October 1601 in Blois, France

Died: 18 August 1652 in Blois, France

Florimond de Beaune's name is often given in the form Debeaune. He was born in Blois, which is in central France on the Loire River and, at the time de Beaune was born there, it was almost a second capital of France. Florimond de Beaune's father, also called Florimond de Beaune, was the illegitimate son of Jean II de Beaune whose brother was the archbishop Renaud de Beaune. However Florimond senior was made legitimate and inherited the title which eventually went to his son, the subject of this biography. Florimond de Beaune senior was a squire with an estate being the Seigneur de Goulioux. Florimond de Beaune, the mathematician, inherited the estate from his father, so he also became Seigneur de Goulioux.

De Beaune was educated in Paris where he went on to study law although his status meant that he had no need to take a degree. After military service he had little need for earning a living. He married Philiberte Anne Pelluis on 21 December 1621 but the marriage lasted less than a year since she died in August 1622. He married Marguerite du Lot on 15 December 1623; this second marriage brought considerable wealth to de Beaune. The marriage produced three sons and one daughter; one of the sons became a priest. De Beaune bought the office of counselor to the court of justice in Blois, and was only an amateur mathematician. He inherited an estate near Blois and he spent a lot of his time on this estate. As we noted, his second marriage brought de Beaune a substantial amount of money. It enabled him to build up an extensive library as well as to build himself an observatory at the town house which he also owned. In fact his library contained a good proportion of astronomy works (about a third of the total) in addition to a fine collection of mathematics volumes. In [7] Pierre Costabel examines an inventory of de Beaune's library drawn up after his death by his heirs. He draws some conclusions:-

(1) Nothing in Greek is represented in the library.

(2) The classification by authors shows that de Beaune possessed all the works by Kepler, Galileo, Descartes and J-B Morin published at that time, and most of those of Mersenne and Gassendi.

(3) The classification by subjects shows an equal division between works on science and those on general culture.

(4) The places of publication show the facility of obtaining works published outside of France.

It is unfortunate that little of de Beaune's mathematical work survives although Paul Tannery was able, from correspondence of de Beaune's that he discovered, to come to interesting conclusions. De Beaune posed a number of challenging problems [1]:-

According to Beaugrand, the first of these problems - which in the present state of textual study appears to concern itself only with the determination of the tangent to an analytically defined curve - interested Debeaune "in a design touching on dioptrics." As to the second of these problems, the one that has been particularly identified with Debeaune and that ushered in what was called at the end of the seventeenth century the "inverse of tangents" i.e., the determination of a curve from a property of its tangent - Debeaune told Mersenne on 5 March 1639 that he sought a solution with only one precise aim: to prove that the isochronism of string vibrations and of pendulum oscillations was independent of the amplitude. This statement, which is not easily justified except in the language of differential and integral calculus, was fifty years ahead of scientific developments and - by itself - reveals Debeaune's singular ability to translate physical questions into the abstract language of mathematical analysis, despite the inadequacies of the operative means of his time.

De Beaune did, however, publish some work for he produced the first important introduction to Descartes' cartesian geometry. He wrote Notes brièves which was published in 1649 as part of the first Latin edition of Descartes' La Géométrie. De Beaune proved among many results that y2 = xy + bx, y2 = -dy +bx, y2 = bx - x2 represent hyperbola, parabola and ellipse respectively. Two other papers by de Beaune on algebra appeared as part of the second edition of La Géométrie. In fact de Beaune and Descartes were good friends and corresponded frequently on mathematical topics. Many of the top French scientists of the time corresponded with de Beaune, for example Claude Mydorge, Jacques de Billy and Marin Mersenne, and friends visited him to discuss mathematical topics, for example Descartes and Erasmus Bartholin. When he was very ill near the end of his life, de Beaune entrusted Bartholin with several manuscripts and asked him to arrange for their publication. The two algebra papers published in the second edition of La Géométrie were among these manuscripts, but the others were not published by Bartholin and appeared lost. However, in 1963, La doctrine de l'angle solide construit sous trois angles plans was discovered [11]:-

De Beaune intended ... 'Doctrine de l'angle solide construit sous trois angles plans' for posthumous publication, but the treatise never found its way into print because of the complexity of its accompanying diagrams. Every trace of the work was lost until 1963, when it was rediscovered among manuscripts in the Roberval Archive at the Académie des Sciences in Paris, and thus it appears for the first time in the present critical edition (the book [2]). The treatise is of interest chiefly because it is a work of pure synthetic geometry consisting of some 125 propositions composed in the style of Euclid by one of the ablest practitioners of the new analytical art typified by the works of Descartes and Fermat. And while he built on results found in works on trigonometry by Snell, Girard, and Briggs, de Beaune avoided the numerical methods employed by these and other mathematical practitioners of the period in favour of pure geometry, indicating that he distinguished clearly between two genres of mathematics.

De Beaune was also interested in mechanics and optics and wrote on these topics. However his work in these areas was never published and little is known of these contributions. We do know from Mersenne that de Beaune wrote Méchaniques and we know from Frans van Schooten that he wrote Dioptrique. Historians still have some hope that manuscripts of these will be found one day. His interest in optics was related to his interest in astronomy for he worked on grinding lenses, in particular experimenting with non-spherical lenses. De Beaune gained the reputation of being the finest instrument maker of his day which is why Descartes wrote to de Beaune in March 1639. Descartes had designed a machine for grinding hyperbolic lenses that he described in La Dioptrique and he asked de Beaune if he could make the instrument. De Beaune became obsessed with the idea of making Descartes' machine to grind lenses and devoted his whole time to the project. Descartes knew that de Beaune was the only person who had the technical proficiency, a deep understanding of mathematics and a fascination with astronomy. However in January 1640, despite his expertise, de Beaune cut his hand badly on a piece of roughly shaped glass which he was trying to cut into a hyperbolic shape. When Descartes heard about the accident he seemed pleased that his scientific imagination went beyond what the best technician could make. He wrote to Christiaan Huygens's father:-

Do you think I am saddened by this? On the contrary, I tell you that in the very failure of the hands of the best craftsman, I understand just how far my reasoning has reached.

Several years after the accident, de Beaune returned to the topic of lenses but by this time he was more interested in the theory than in grinding lenses. His last few years were painful ones [1]:-

Afflicted with various and painful infirmities, particularly gout, Debeaune resigned as counselor around 1648 and withdrew to a town house, the upper floor of which faced due south. There he had - at least for a time - an observatory at his disposal. However, his failing eyesight deteriorated rapidly, and he died shortly after having a foot amputated.

Let us end this biography with two quotes. The first from Costabel [2]:-

Florimond de Beaune appears in light of his library to have been an enlightened Christian and an erudite humanist, unencumbered by philosophical tradition and quite open to the ideas of his age.

The second quote is from de Beaune himself in a letter he wrote to Mersenne on 5 March 1639:-

I do not think that one could acquire any solid knowledge of nature in physics without geometry, and the best of geometry consists of analysis, of such kind that without the latter it is quite imperfect.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

5 علامات تحذيرية قد تدل على "مشكل خطير" في الكبد

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

لحماية التراث الوطني.. العتبة العباسية تعلن عن ترميم أكثر من 200 وثيقة خلال عام 2024

|

|

|