Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-01-22

Date: 2024-01-02

Date: 29-7-2021

|

Modifying central properties (b)

Adjectives can also, as in (1), modify one or more central properties of N,1 asserting either that they are completely or exclusively satisfied by N, or that the noun – which must have a perfectly identified referent – can efficiently fulfill such property/ies. The first function corresponds to Quirk’s “restrictive” adjectives2 like perfecto ‘perfect,’ and to “degree and quantifying” adjectives3 like verdadero ‘real,’ simple ‘utter,’ or completo ‘complete’;4 the second one corresponds to qualitative-evaluative adjectives like bueno ‘good,’ pequeño ‘little,’ sagrado ‘sacred,’ suave ‘gentle,’ amable ‘kind,’ and color, form, and taste adjectives like verde ‘green,’ acido ‘acidic’.

Following standard assumptions, it might be difficult to accept that these two sets of adjectives belong to the same logical type since restrictive adjectives, and those of degree, are usually considered predicate modifiers (functions from properties to properties) while qualitative adjectives generally denote properties. What I want to emphasize with this regrouping is the fact that most adjectives in (1) license the entailment “NP is N” (“a good lawyer is a lawyer”) but they do not license the entailment that “NP is Adj” (“a good lawyer is not necessarily good in general terms”). In a similar way, a complete failure is a failure which is complete as a failure, and un verdadero coche is a car which satisfies the properties which distinguish cars within a larger domain. Neither of them implies, respectively, el fracaso es completo “the failure is a subset of the ‘complete things” or el coche es verdadero “the car is real.”

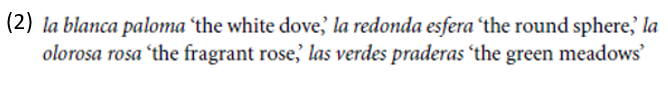

Different with regard to this entailment are qualitative evaluative adjectives, specifically sensorial quality adjectives such as white, acidic, round, etc.: a white palace is obviously a white object. In traditional grammars of Spanish it is usual to call these color, shape, and taste adjectives epithets, as they emphasize the prototypical elements in the meaning of the noun, and this is the main characteristic of the attributive NR interpretation when resulting from the use of these forms:

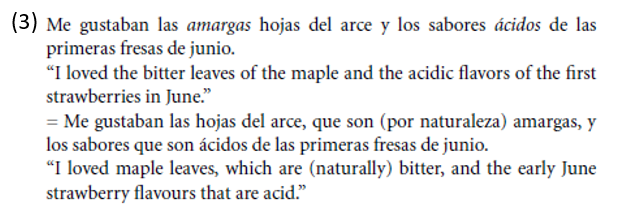

In fact, these adjectives cannot be prenominal in certain Romance languages like French (Laenzlinger 2005, Knittel 2005, among others). Even in Spanish these adjectives are not frequent in prenominal position. These lexical subtypes of adjectives (color, form, taste, and other sensorial properties) tend to be used postnominally, and are typically predicative, since they are intersective. Nevertheless, their function when used prenominally is not that of intersecting the class of objects denoted by the noun and the property expressed by the A, but rather that of “affecting” the denotation of the unique object(s) expressed by N. Observe the contrast between the sensorial adjectives in (3):

In (3) both taste adjectives occur in very similar contexts, [N+PPrestrictive], but the first is prenominal and the second postnominal. They are both predicates that denote properties of N; however, the first one has to be glossed through an appositive relative clause while the postnominal one is equivalent to a restrictive relative.

In this sense prenominal sensorial adjectives (the epithets) have an interpretive role very similar to that of ‘restrictive’ and degree adjectives (cf. 1). At least as a speculation it can be said that in both cases (non-intersective restrictive– degree adjectives and prenominal qualitative–evaluative adjectives) the adjectives modify a hidden parameter of N. We might claim, as in Pustejovsky (1995), that “every category expresses a qualia structure” and that certain nouns (and the NPs containing them) encode information about particular activities or properties associated with them. In this framework, restrictive degree modifiers and qualitative epithetic adjectives can be considered modifiers of the formal quale of N, namely, “the aspects of a word’s meaning that distinguish (the object) within a larger domain” (Pustejovsky 1995: 76). I will come back to this aspect of the semantic relation between N and A in the next section, where I will present some speculations about why these structural meanings appear mainly when the adjective occurs in prenominal position.

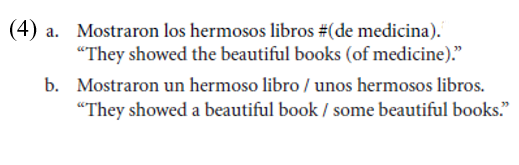

Finally, the class of prenominal adjectives that I describe as modifiers of a central property can have this function only when the DP identifies unique referents. This is the reason why these prenominal adjectives are more common in definite DPs and require modifiers restricting the reference of NP (4a). Without the modifier, the sentences are acceptable if the DP refers to a previously introduced referent. In the same vein, they are normal in singular and plural indefinite expressions (4b), since these DPs introduce referents in the discourse:

1 “Modifier of central properties” is an informal way to describe what is usually called “reference modification.”

2 The term “restrictive adjective” is taken from Quirk et al. (1978: §7.35), where it refers to those adjectives orienting the interpretation towards the uniqueness of the referent.

3 Degree and quantifying adjectives indicate “the degree to which the property expressed in the head nominal applies in a given case” (Pullum and Huddleston 2002: 555).

4 Larson (1998: 10) also says that utter, mere, and complete “cannot be analyzed as simple, univocal predicate of events [like former]. Rather they appear to be forms whose relation to N parallels the relation of a degree modifier to an associated A.”

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|