Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-09-14

Date: 2023-08-25

Date: 15-1-2022

|

We noted that much the most common kind of compound in English is the compound noun, whether primary (e.g. hairnet) or secondary (e.g. hair restorer). It is on compound nouns of the NN type that I will concentrate here. It turns out that primary and secondary compounds are both highly regular formally, but only secondary compounds are highly regular semantically. Again, therefore, the distinction between formal and semantic regularity turns out to be useful.

As we noted, the most natural way to interpret hair restorer is ‘substance for restoring hair growth’; that is, to interpret the first component (hair) as the object of the verbal element in the second (restore). A secondary compound for which this mode of interpretation yields the right meaning is semantically regular, therefore. All the secondary compounds, namely sign-writer, slum clearance, crime prevention, wish-fulfilment, are semantically regular. But there exist also semantically irregular compounds with the appearance of secondary compounds:

(4) machine-washing, globe-trotter, voice-activation

Machine-washing may in some context be interpreted ‘washing of machines’, but more often it means washing in a washing-machine, as opposed to by hand. A globe-trotter is someone who travels around the world a lot, not someone who ‘trots globes’ (whatever that would mean). In voice-activation, it is not a voice that is activated but rather a machine (say, a computer) that is activated by spoken commands rather than by a keyboard or mouse.

There is room for debate whether these are secondary compounds of a semantically unusual kind, or primary compounds in which the second component just happens to be derived from a verb. How is it most useful to define the term ‘secondary compound’: more narrowly, so that the first component must be the object of the verbal element, or more widely, so as to permit the first component to be related to the verbal element in some other way, for example as instrument (machine-washing) or location (globe-trotter)? It is not important to give a firm answer to that question here. What one can say, however, is that the semantic unpredictability of the examples at (4) is far from unusual among NN compounds; in fact, it is a kind of unpredictability shared by all primary compounds. The discussion of hairnet, mosquito net and butterfly net. It is not the structure of these compounds, in conjunction with the meanings of the components, that tells us precisely what each stands for; rather, it is our knowledge of the world, such as the difference in the ways that mosquitos and butterflies impinge on human beings. Primary NN compounds are thus intrinsically irregular semantically, in that their exact interpretation is unpredictable without the help of this sort of real-world knowledge.

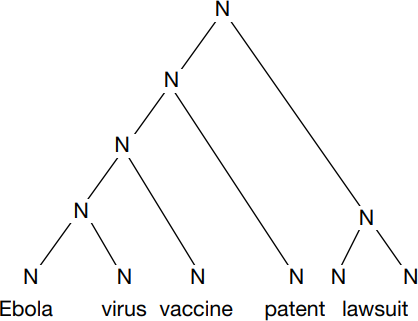

The semantic irregularity of primary compounds does not entail any formal irregularity, however. In fact, any two nouns whatever can be juxtaposed in English to produce a formally acceptable root compound. For example, bóat moon and brídge cloud, with stress on the first element as indicated, are possible English nouns even though neither has ever been used (so far as I know) and it is not clear what either of them would mean except in the vaguest terms (‘moon associated somehow with boats’ and ‘cloud associated somehow with bridges’). This semantic vagueness may seem to present an intolerable obstacle to the creation of new root compounds. However, the obstacle is smaller than it may at first seem, for two reasons. Firstly, the elements in a new root compound XY may be such that even the vague interpretation ‘Y somehow associated with X’ is precise enough for practical purposes. For example, consider the elaborate compound word in (5), which might conceivably figure in a newspaper headline:

The fact that a reader has never encountered this compound before is no barrier to understanding it, just on the strength of general knowledge about the patentability of drugs. Secondly, even in more obscure cases, we instinctively grasp at contextual clues to fill in semantic gaps. I will illustrate this with an actual example.

It is unlikely that any readers have previously encountered the compound cup bid float, and unlikely too that many readers, having now encountered it, will be able to hazard much of a guess as to its meaning. Yet it is a word that actually appeared in the The Press newspaper in Christchurch, New Zealand, on 14 April 1994. The Press had a column on the front page summarizing the main stories on inside pages. Cup bid float appeared as the headline for one of these summaries, which continued: ‘New Zealanders will be offered the chance to buy shares in the company that will finance yachtsman Chris Dickson’s bid to win the America’s Cup next year.’ With just that much contextual information, the interpretation of the enigmatic headline becomes clear. Cup denotes the America’s Cup, cup bid denotes an attempt to win it (bid being an alternative to attempt that is favored in newspaper headlines for the sake of brevity), and float refers to the floating of a limited company, i.e. the offer of shares in it on the share market. The fact that the headline cannot be interpreted without the help of the paragraph that it introduces hardly matters, from the journalist’s point of view; it has served its purpose if it has persuaded readers to read on.

English makes more generous use of compounding than many other European languages do, so it is hardly surprising that at least some kinds of compounding should be formally regular and also highly general. What is more surprising is that such a general process should be so vague semantically. Interpretation of new compounds relies in practice less on strictly linguistic regularities than on context and general knowledge.

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي ينظّم ندوة حوارية حول مفهوم العولمة الرقمية في بابل

|

|

|