Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-01-06

Date: 10-3-2022

Date: 25-2-2022

|

Anglo-Norman in modern Britain

Language shift happens by gradual replacement of one language by another in all of its functions. In England, the H language functions gradually shifted from Anglo-Norman to English over the course of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, but Anglo-Norman retains some vestigial functions even today.

Towns associated with the Cinque Ports signpost this historical status in Anglo-Norman, and the highest order of chivalry within the British honours system, the Royal Order of the Garter, which dates from 1348, has an Anglo-Norman motto: Honi soit qui mal y pense (‘Evil be to him who evil thinks’).

When the British government presents proposals for Royal Assent, the responses on behalf of the Monarch are still given in Anglo-Norman, for example: ‘La Reyne remercie ses bons sujets, accepte leur benevolence, et ainsi le veult’ (The Queen thanks her good subjects, accepts their bounty, and wills it so) or ‘La Reyne/Le Roy le veult’ (The Queen/King wills it).

Once a standard variety had been selected, elaboration of function soon followed as English replaced Anglo-Norman as the language of record and of government, and increasingly ousted Latin from its pre-eminent position as the language of education. To fulfil its new roles, English borrowed extensively, notably between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, from Norman and central French, Greek and Latin.

Expansion of English predictably brought calls for codification, including proposals in the eighteenth century by the author Jonathan Swift, among others, for the establishment of an Academy along the lines of the Italian Accademia della Crusca or the French Académie Française to serve as an arbiter for ‘correct’ usage. These were impractical, but this period saw a profusion of prescriptive grammars and the first authoritative dictionary, Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1755. This remained the pre-eminent reference work on the English lexicon until publication of the Oxford English Dictionary nearly 150 years later. It is this codified variety of English, often referred to as the ‘Queen’s’ or ‘King’s’ English which became accepted as the variety taught in England’s public (i.e. private and exclusive) schools, and later used by the BBC and other public institutions.

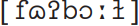

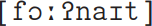

The norms of standard English are not fixed, but constantly contested and subject to change. Lexical items such as gay or wicked have changed their meanings in the last 30–40 years, and pronunciations deemed unacceptable by the BBC in the immediate post-war years have become standard. Even RP users, for example, now tend to use glottal stops in preconsonantal position (e.g. football  , fortnight

, fortnight  ), and the CAT vowel has now lowered to [a] from [æ]. A good way to stir up controversy is to say the word controversy on British broadcast media: its pronunciation provokes a flurry of animated comment from the self-appointed guardians of the language, some convinced that the first syllable should be stressed (CONtroversy), others equally adamant that the stress should fall on the second (conTROVersy). All this tends to confirm the suggestion by Lesley and James Milroy in Authority in Language that standardization is best seen as an ideology, in which the ideal of one correct form for one meaning is never actually achieved.

), and the CAT vowel has now lowered to [a] from [æ]. A good way to stir up controversy is to say the word controversy on British broadcast media: its pronunciation provokes a flurry of animated comment from the self-appointed guardians of the language, some convinced that the first syllable should be stressed (CONtroversy), others equally adamant that the stress should fall on the second (conTROVersy). All this tends to confirm the suggestion by Lesley and James Milroy in Authority in Language that standardization is best seen as an ideology, in which the ideal of one correct form for one meaning is never actually achieved.

|

|

|

|

5 علامات تحذيرية قد تدل على "مشكل خطير" في الكبد

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

تستخدم لأول مرة... مستشفى الإمام زين العابدين (ع) التابع للعتبة الحسينية يعتمد تقنيات حديثة في تثبيت الكسور المعقدة

|

|

|