Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-10-12

Date: 2023-08-09

Date: 2023-09-13

|

Inflectional morphology

We saw in the definition of lexemes above that in some cases different words are related by rule, and perceived to be forms of the same word. A dictionary would not, for example, list book and books separately, because the latter can be formed from the other. Furthermore, the meaning is entirely predictable: if you know what book is then you know what the plural form books means.

This kind of morphology, in which words are modified to express grammatical categories, is known as inflectional morphology. It does not involve the creation of new words, and the markings involved are subject to grammatical rule. Nouns, or more precisely count nouns, in English are marked for number, having generally a singular and a plural form, even if some of these forms are irregular (child, for example, has an irregular plural form: one child, many children). English verbs may be marked for tense, aspect and person: for the verb decide, for instance, we can identify four separate forms:

1 decide (infinitive; all present tenses except the third person)

2 decides (third person, present tense)

3 deciding (present progressive/present participle/gerund)

4 decided (past tense/past participle/passive participle)

The morpheme (marked in bold) which marks the particular grammatical function in question is often referred to as the exponent, thus -ed above is the exponent of <past> in English for decide and many other regular verbs.

Languages differ considerably in the richness of their inflectional morphology. Isolating languages, for example Mandarin or Vietnamese, have little or no inflectional morphology: the concept of ‘plural’ in Mandarin for example has to be deduced from context (one dog, two dog, many dog and so on) and is not marked on the noun itself. Russian or Latin, by contrast, are examples of highly inflecting languages: both Latin and its daughter language, Portuguese, for example, have full verbal paradigms in which all persons in all tenses are marked by a suffix (compare English, which marks only third person singular in the present tense). In both Latin and Russian, nouns are additionally marked for case, indicating by means of a suffix their function within a sentence. English, which has lost most of its case marking except in pronouns (compare she as a subject or nominative form, and her as an accusative or object form), achieves this through word order (subjects tend to precede verbs, objects follow them), or by prepositions. In Russian, these endings vary according to the gender of the noun, and there is a separate plural form.

Note that the genitive plural form for a regular feminine noun like kniga contrasts with the rest by virtue of adding nothing to the stem knig-. Because it contrasts with realized suffixes in all the other cases, this ‘nothing’ is actually meaningful: in cases like this, it makes sense to talk of a zero morpheme. Similarly, for plurals such as sheep, fish or deer in English, there is a strong case, however counter-intuitive it might appear, for arguing that these are all in fact stem+Ø (zero) sequences: this enables us to maintain our generalization that plurals in English are generally formed by addition of a suffix.

In practice, the classification of languages into ‘inflecting’ and ‘isolating’ types should not be thought of in absolute terms, but rather as a continuum in which English is rather less inflecting than, say, Russian, Latin or Basque, but more inflecting than Vietnamese or Tok Pisin. A third type of language, known as agglutinating, is, however, exemplified by Turkish, Hungarian, Aleut and Finnish. In agglutinating languages, words are built up from morphemic blocks, each of which has a single meaning or grammatical function.

Consider the verb ‘to make’ in Turkish:

yap verb stem/imperative

yapmak infinitive

yapiyor present tense

yapiyorsun ‘you make/are making’

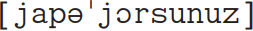

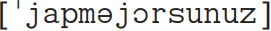

yapiyorsunuz ‘you (plural) make/are making’

The one-form to one-meaning relationship in Turkish is clearly exemplified here: yap provides the verb stem, iyor marks present tense, sun second person and finally uz marks plural.

In an inflecting language, affixes often have more than one function, as illustrated by the past tense paradigm of the Spanish verb hablar (to speak):

1st pers. sg. yo hablé

2nd pers. sg. tu hablaste

3rd pers. sg. el/ella habló

1st pers. pl. nosotros hablamos

2nd pers. pl. vosotros hablasteis

3rd pers. pl. ellos/ellas hablaron

In each case a single suffix marks the categories of person, tense and number: thus é in hablé is the exponent of <1st person>, <singular> and <past>, and we cannot, as in Turkish, find a specific marker for each of these properties. In this case, the relationship between form and grammatical properties is one to many, but the reverse relationship, in which a single grammatical property is marked more than once, is also common. A good example is negation in Turkish:

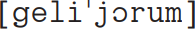

geliyorum  I’m coming

I’m coming

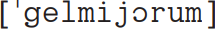

gelmiyorum  I’m not coming

I’m not coming

yapıyorsunuz  you are making

you are making

yapmıyorsunuz  you are not making

you are not making

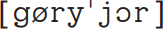

görüyor  he/she is seeing

he/she is seeing

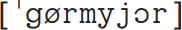

görmüyor  he/she is not seeing

he/she is not seeing

In each of these examples, negation is realized by an infix -m-, but there is also a change of stress position, so the negation is doubly marked.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|