Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-11-23

Date: 2023-10-30

Date: 2023-11-11

|

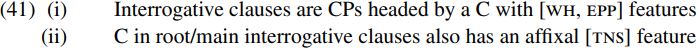

Underlying the analyses we have presented so far is the assumption that questions in English have the following syntactic properties:

The [WH, EPP] features of C trigger movement of a wh-expression to spec-CP; and the affixal [TNS] feature carried by C in main-clause questions triggers movement of an auxiliary or tense affix from T to C (with a moved tense affix requiring concomitant do-support).

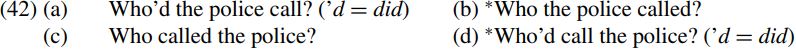

However, the assumptions made in (41) raise interesting questions about how we account for the contrast in (42) below:

(42a,b) are wh-object questions, in the sense that the preposed interrogative expression who is the direct object complement of the verb call; as would be expected from the assumption in (41ii) that C in main-clause questions carries an affixal [TNS]feature, they require T-to-C movement and concomitant DO-support. By contrast, (42c,d) are wh-subject questions, in the sense that who is the subject of the verb call; contrary to what (41ii) would lead us to expect, wh-subject questions do not allow T-to-C movement and do-support. (More precisely, do can be used if it is emphatic, receives contrastive stress and is spelled out as the full form did – as in Who DID call the police? with capitals marking contrastive stress.) Why should this be?

One answer to this question (different versions of which are suggested in Radford 1997a and Agbayani 2000) is the following. Let’s suppose that T-to-C movement (and concomitant do-support) is only found in questions in which a wh-expression moves to spec-CP. In wh-object questions like (42a,b) it is clear that the wh-pronoun who moves to spec-CP, since it is the object of the verb call and if it had not moved to spec-CP, it would have been positioned after the verb (as in the echo question The police called who?). But in wh-subject questions like (42c,d) it is by no means clear that the wh-pronoun who has moved into spec-CP, since even if it remained in situ in spec-TP it would still end up as the first overt constituent in the sentence. Let’s therefore consider the possibility that in sentences like (42c,d) where a wh-expression is the subject of the overall interrogative clause, the wh-expression remains in situ in spec-TP and does not move to spec-CP. If T-to-C movement and concomitant do-support are only found in questions which involve movement of a wh-expression to spec-CP, and if wh-subject questions do not involve wh-movement to spec-CP, we can seemingly account for the absence of do-support in wh-subject questions like (42c,d).

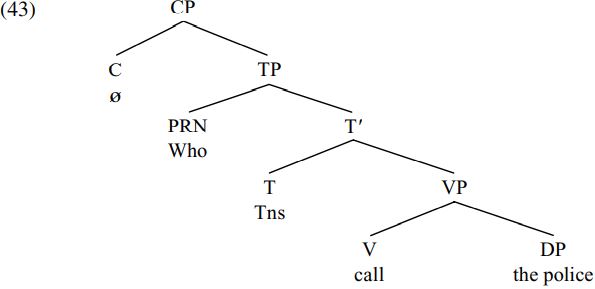

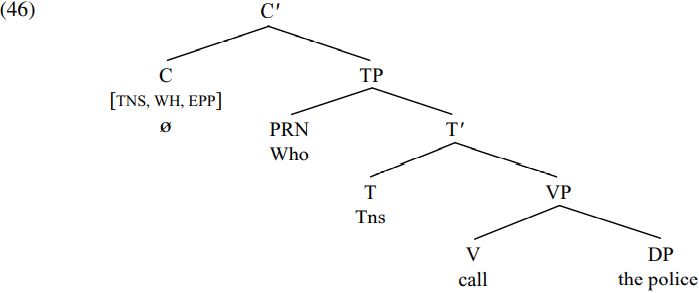

On this view, the derivation of (42c) would proceed as follows. The determiner the merges with the noun police to form the DP the police. This DP is then merged with the verb call to form the VP call the police. The resulting VP is in turn merged with a past-tense affix Tns, forming the T-bar Tns call the police. This T-bar is then merged with the pronoun who, forming the TP who Tns call the police. If we follow Agbayani (2000) in supposing that all interrogative clauses are CPs, the resulting TP will be merged with an interrogative C to form the CP shown in simplified form below:

The past-tense affix in T will be lowered onto the main verb by Affix Hopping in the PF component, so that the verb is spelled out as called in (42c) Who called the police?

However, the spec-TP analysis of wh-subjects outlined in (43) above raises a number of questions. For example, why isn’t the wh-pronoun who in (43) attracted to move to spec-CP and why isn’t there any T-to-C movement if C always has [TNS, WH, EPP] features in main-clause questions as claimed in (41) above? Maintaining the claim in (41) that C in main-clause questions always has [TNS, WH, EPP] features at the same time as maintaining the wh-in-situ analysis of wh-subject questions in (43) is going to require considerable ingenuity: for example, we might suppose that the [TNS, WH, EPP] features of C only trigger wh-movement and T-to-C movement when the relevant wh-expression is c-commanded by T. This would mean that C triggers both wh-movement and T-to-C movement in a structure like (35) because the closest wh-expression to C (= which assignment) is c-commanded by T; but it would also mean that there is neither wh-movement nor T-to-C movement in a structure like (43) because the closest wh-expression to C (= who) is not c-commanded by T. However, even this (somewhat contrived) analysis leaves us without a principled explanation of how the [TNS, WH, EPP] features of C are deleted in a structure like (43) which shows neither wh-movement nor T-to-C movement.

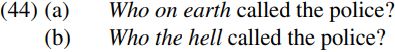

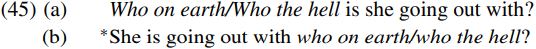

Moreover, the core assumption underlying the analysis in (43) above (viz. that the wh-subject remains in spec-TP in wh-subject questions like (42c) Who called the police?) is called into question by the observation by Pesetsky and Torrego (2001) that who in (42c) can be substituted by who on earth or who the hell:

As Pesetsky (1987) notes (and as the examples in (45) below illustrate), wh-expressions like who on earth and who the hell have the property that they cannot remain in situ, but rather must move to spec-CP:

If wh-expressions like those italicized in (45) always move to spec-CP, it follows that the italicized subjects in (44) must likewise have moved to spec-CP – and hence it is plausible to suppose that the same is true of the subject who in (42c) Who called the police? (See den Dikken and Giannakidou 2002 for more detailed discussion of the syntax and semantics of expressions like who the hell?)

Let’s therefore follow Pesetsky and Torrego in taking all wh-questions (including wh-subject questions) to be CPs which show movement of a wh-expression to spec-CP. In particular, let’s suppose that after the TP who Tns call the police has been formed, it is merged with an interrogative C constituent which carries [TNS, WH, EPP] features, so forming the structure in (46) below (cf. (43) above):

What we might expect to happen at this point is for the [WH, EPP] features of C to attract who to move to spec-CP, and for the [TNS] feature of C to attract movement of the Tns affix from T to C, with the dummy auxiliary do being attached to the affix in the PF component in order to provide it with a host. But such a derivation would wrongly predict that (42d) ∗Who’d call the police? is grammatical on the relevant interpretation (where ’d is a contracted form of did). So it would seem that the [TNS] feature of C does not attract the head T constituent of TP. So what does it attract?

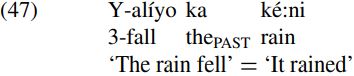

The answer given by Pesetsky and Torrego is that the [WH] and [TNS] features of C both attract the nominative wh-pronoun who, with the [EPP] feature of C ensuring that who moves to spec-CP. A key assumption underlying Pesetsky and Torrego’s analysis is that the word who (by virtue of being the subject of a tensed clause) carries a tense feature as well as a wh-feature. More specifically, they posit that agreement between T and its subject involves not only copying the person/number features of the subject onto T but also (conversely) copying the tense feature of T onto the subject. This is far from implausible from a cross-linguistic perspective, since in languages like Chamicuro, tense is overtly marked on subjects, as the following example (from Parker 1999, p. 552) shows:

In (47), the head D ka ‘the’ of the subject DP ka ke:ni ´ ‘the rain’ is a past-tense determiner (the corresponding non-past determiner being na), providing clear evidence of tense-marking on the subject. If tense-marking of subjects also takes place in English, we can assume that a tensed T will have a tensed subject, so that who in Who called the police? will be a past-tense subject by virtue of being the subject of a past-tense T. Now, at first sight this might seem implausible, since who doesn’t carry the regular past-tense suffix -d: however, this is because -d is a verbal suffix which attaches only to (regular) verbs, hence not to a pronoun like who. Pesetsky and Torrego claim that the tense feature carried by the subject of a tensed clause in English is manifested as nominative case, so that a nominative subject is really a subject carrying a tense feature. On this view, who in (42c) Who called the police? will carry a tense feature which causes the subject pronoun to be spelled out as the tensed (nominative) form who, rather than as the accusative form whom or the genitive form whose.

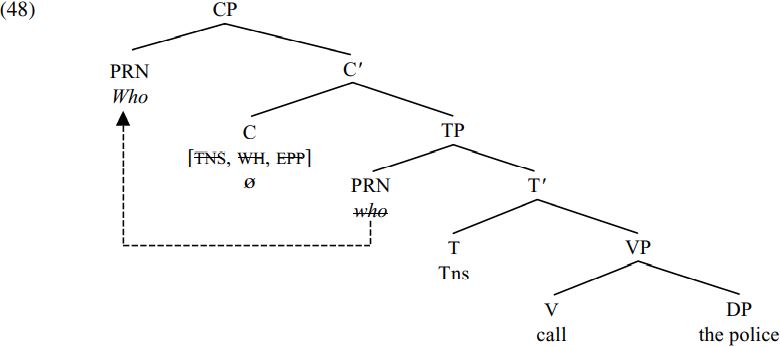

In the light of these assumptions, let’s return to the stage of derivation we reached in (46) above. As assumed in (41), C in a main-clause question carries [TNS], [WH] and [EPP] features: the [TNS] feature of C requires C to attract a tensed constituent to move to the edge of CP, its [WH] feature requires the relevant structure to contain a wh-marked constituent, and its [EPP] feature requires C to project a specifier carrying a feature matching one of the features of C. One way of satisfying these requirements would be to move who from spec-TP to spec-CP, and move (a copy of) the tense affix in T to C (using do-support to provide a host for the affix). However (as we have already seen), this would wrongly predict that a sentence like (42d) ∗Who’d call the police? should be grammatical (where ’d is a clitic form of did). Why should such a derivation (involving two movement operations, WH-MOVEMENT and T-TO-C MOVEMENT) lead to ungrammaticality? Pesetsky and Torrego’s answer is that simply moving who from spec-TP to spec-CP on its own (without T-to-C movement) can satisfy the requirements of all three [TNS, WH, EPP] features of C, and economy considerations dictate that a derivation involving a single movement operation O should be preferred to one involving both O and an additional movement operation. Movement of who to spec-CP can satisfy the [WH] and [EPP] features of C because who carries a wh-feature and moves to spec-CP, and can at the same time satisfy the [TNS] feature of C because who carries a tense feature (by virtue of being the subject of a tensed clause). The resulting derived structure is as follows (with the arrow showing how wh-movement applies):

Since movement of the tensed wh-pronoun who to spec-CP is sufficient to satisfy the requirements of all three features carried by C, economy considerations dictate that T-TO-C MOVEMENT is unnecessary (hence not permitted) in wh-subject question structures, Pesetsky and Torrego reason. (An incidental detail is that the past-tense affix in T will subsequently be lowered onto the head V of VP in the PF component, with the result that the verb call is ultimately spelled out as the past-tense form called.)

Pesetsky and Torrego’s analysis allows us to maintain the generalization in (41) that all main-clause questions are CPs headed by a C constituent carrying [TNS, WH, EPP] features. In non-subject questions, the requirements of the [WH, EPP] features of C are met by moving a wh-expression into spec-CP, and the requirements of its [TNS] feature are met by T-to-C movement. But in questions where the attracted wh-expression is the subject of the interrogative clause, the requirements of all three features are met by moving the wh-subject who (which carries a tense feature by virtue of being the subject of a tensed T) into spec-CP.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|