Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-09-22

Date: 2023-10-23

Date: 2023-10-13

|

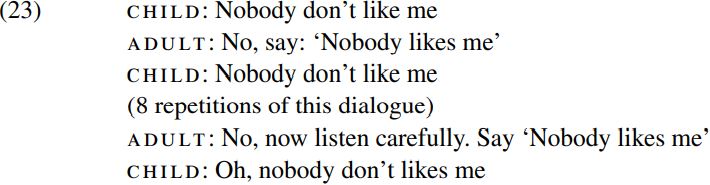

One of the questions posed by the parameter-setting model of acquisition outlined here is just how children come to arrive at the appropriate setting for a given parameter, and what kind(s) of evidence they make use of in setting parameters. As Chomsky notes (1981, pp. 8–9), there are two types of evidence which we might expect to be available to the language learner in principle, namely positive evidence and negative evidence. Positive evidence comprises a set of observed expressions illustrating a particular phenomenon: for example, if children’s speech input is made up of structures in which heads precede their complements, this provides them with positive evidence which enables them to set the Head-Position Parameter appropriately. Negative evidence might be of two kinds – direct or indirect. Direct negative evidence might come from the correction of children’s errors by other speakers of the language. However, (contrary to what is often imagined) correction plays a fairly insignificant role in language acquisition, for two reasons. Firstly, correction is relatively infrequent: adults simply don’t correct all the errors children make (if they did, children would soon become inhibited and discouraged from speaking). Secondly, children are notoriously unresponsive to correction, as the following dialogue (from McNeill 1966, p. 69) illustrates:

As Hyams (1986, p. 91) notes: ‘Negative evidence in the form of parental disapproval or overt corrections has no discernible effect on the child’s developing syntactic ability.’ (For further evidence in support of this conclusion, see McNeill 1966; Brown, Cazden and Bellugi 1968; Brown and Hanlon 1970; Braine 1971; Bowerman 1988; Morgan and Travis 1989; and Marcus 1993.)

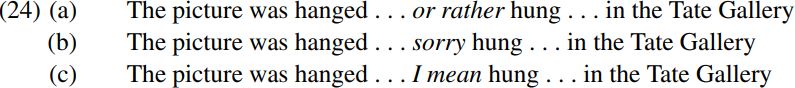

Direct negative evidence might also take the form of self-correction by other speakers. Such self-corrections tend to have a characteristic intonation and rhythm of their own, and may be signaled by a variety of fillers (such as those italicized in (24) below):

However, self-correction is arguably too infrequent a phenomenon to play a major role in the acquisition process.

Rather than say that children rely on direct negative evidence, we might instead imagine that they learn from indirect negative evidence (i.e. evidence relating to the non-occurrence of certain types of structure). Suppose that a child’s experience includes no examples of structures in which heads follow their complements (e.g. no prepositional phrases like ∗dinner after in which the head preposition after follows its complement dinner, and no verb phrases such as ∗cake eat in which the head verb eat follows its complement cake). On the basis of such indirect negative evidence (i.e. evidence based on the non-occurrence of head-last structures), the child might infer that English is not a head-last language.

Although it might seem natural to suppose that indirect negative evidence plays some role in the acquisition process, there are potential learnability problems posed by any such claim. After all, the fact that a given construction does not occur in a given chunk of the child’s experience does not provide conclusive evidence that the structure is ungrammatical, since it may well be that the non-occurrence of the relevant structure in the relevant chunk of experience is an accidental (rather than a systematic) gap. Thus, the child would need to process a very large (in principle, infinite) chunk of experience in order to be sure that non-occurrence reflects ungrammaticality. It seems implausible to suppose that children store massive chunks of experience in this way and search through it for negative evidence about the non-occurrence of certain types of structure. In any case, given the assumption that parameters are binary and single-valued, negative evidence becomes entirely unnecessary: after all, once the child hears a prepositional phrase like with Daddy in which the head preposition with precedes its complement Daddy, the child will have positive evidence that English allows head-first order in prepositional phrases; and given the assumptions that the Head-Position Parameter is a binary one and that each parameter allows only a single setting, then it follows (as a matter of logical necessity) that if English allows head-first prepositional phrases, it will not allow head-last prepositional phrases. Thus, in order for the child to know that English doesn’t allow head-last prepositional phrases, the child does not need negative evidence from the non-occurrence of such structures, but rather can rely on positive evidence from the occurrence of the converse order in head-first structures (on the assumption that if a given structure is head-first, UG specifies that it cannot be head-last). And, as we have already noted, a minimal amount of positive evidence is required in order to identify English as a uniformly head-first language (i.e. a language in which all heads precede their complements). Learnability considerations such as these have led Chomsky (1986a, p. 55) to conclude that ‘There is good reason to believe that children learn language from positive evidence only.’ The claim that children do not make use of negative evidence in setting parameters is known as the No-Negative-Evidence Hypothesis; it is a hypothesis which is widely assumed in current acquisition research. (See Guasti 2002 for a technical account of language acquisition within the framework used here.)

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي ينظّم ندوة حوارية حول مفهوم العولمة الرقمية في بابل

|

|

|