Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-02-21

Date: 2024-04-23

Date: 2023-10-20

|

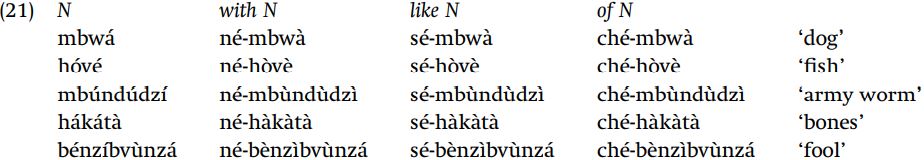

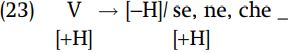

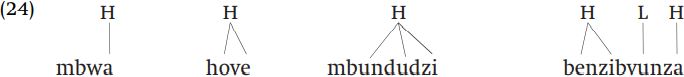

Another phenomenon which argues for the autosegmental representation of tone is across-the-board tone change. An illustration of such a tonal effect can be found in Shona. The examples in (21) show that if a noun begins with some number of H tones, those H’s become L when preceded by one of the prefixes né-, sé-, and ché.

As shown in (22) and by the last example of (21), an H tone which is not part of an initial string of H’s will not undergo this lowering process.

The problem is that if we look at a word such as mbúndúdzí as having three H tones, then there is no way to apply the lowering rule to the word and get the right results. Suppose we apply the following rule to a standard segmental representation of this word.

Beginning from /né-mbúndúdzí/, this rule would apply to the first H-toned vowel giving né-mbùndúndzí. However, the rule could not apply again since the vowel of the second syllable is not immediately preceded by the prefix which triggers the rule. And recall from examples such as né-mùrúmé that the rule does not apply to noninitial H tones.

This problem has a simple solution in autosegmental theory, where we are not required to represent a string of n H-toned vowels as having n H tones. Instead, these words can have a single H tone which is associated with a number of vowels.

Given these representations, the tone-lowering process will only operate on a single tone, the initial tone of the noun, but this may be translated into an effect on a number of adjacent vowels.

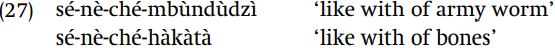

There is a complication in this rule which gives further support to the autosegmental account of this process. Although this process lowers a string of H tones at the beginning of a noun, when one of these prefixes precedes a prefixed structure, lowering does not affect every initial H tone. When one prefix precedes another prefix which precedes a noun with initial H’s, the second prefix has an L tone and the noun keeps its H tones.

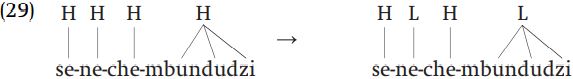

However, if there are three of these prefixes, the second prefix has an L tone, and lowering also affects the first (apparent) string of tones in the noun.

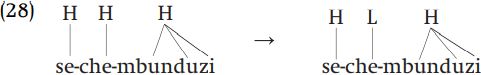

A simple statement like “lower a sequence of adjacent H’s” after an H prefix would be wrong, as these data show. What we see here is an alternating pattern, which follows automatically from the rule that we have posited and the autosegmental theory of representations. Consider the derivation of a form with two prefixes.

The lowering of H on che gives that prefix an L tone, and therefore that prefix cannot then cause lowering of the H’s of the noun. On the other hand, if there are three such prefixes, the first H-toned prefix causes the second prefix to become L, and that prevents prefix 2 from lowering prefix 3. Since prefix 3 keeps its H tone, it therefore can cause lowering of H in the noun.

Thus it is not simply a matter of lowering the tones of any number of vowels. Unlike the traditional segmental theory, the autosegmental model provides a very simple and principled characterization of these patterns of tone lowering.

|

|

|

|

"عادة ليلية" قد تكون المفتاح للوقاية من الخرف

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ممتص الصدمات: طريقة عمله وأهميته وأبرز علامات تلفه

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ندوات وأنشطة قرآنية مختلفة يقيمها المجمَع العلمي في محافظتي النجف وكربلاء

|

|

|