Flapping

المؤلف:

David Odden

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

20-2

الجزء والصفحة:

20-2

24-3-2022

24-3-2022

1289

1289

Flapping

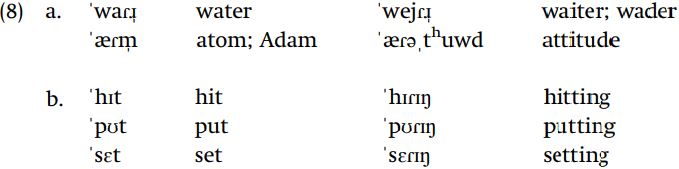

We now turn to another rule. A phonetic characteristic of many North American dialects of English is “flapping,” where /t/ and /d/ become the flap [ɾ] in certain contexts, for example in [ˈwaɾɹ̩] water. It is clear that there is no contrast between the flap [ɾ] and any other consonant of English: there are no minimal pairs such as hypothetical [hɪt] and *[hɪɾ], or *[bʌtɹ̩] and [bʌɾɹ̩], whose existence would establish that the flap is a distinct phoneme of English. Moreover, the contexts where the flap appears in English are quite restricted. In our previous examples of nonaspiration in the context ˈvCv in (4) and (6), no examples included [t] as an intervocalic consonant. Now consider the following words:

In (8a) orthographic is phonetically realized as the flap [ɾ] in the context ˈV_V, that is, when it is followed by a vowel or syllabic sonorant – represented as V – and preceded by a stressed vowel or syllabic sonorant. Maybe we have just uncovered an orthographic defect of English, since we have no letter for a flap (just as no letter represents /θ/ vs. /ð/) and some important distinctions in pronunciation are lost in spelling. The second set of examples show even more clearly that underlying t becomes a flap in this context. We can convince ourselves that the verbs [hɪt], [pʊt] and [sεt] end in [t], simply by looking at the uninflected form of the verb, or the third-person-singular forms [hɪts], [pʊts] and [sεts], where the consonant is pronounced as [t]. Then when we consider the gerund, which combines the root with the suffix -ɪŋ, we see that /t/ has become the flap [ɾ]. This provides direct evidence that there must be a rule deriving flaps from plain /t/, since the pronunciation of root morphemes may actually change, depending on whether or not the rule for flapping applies (which depends on whether a vowel follows the root).

There is analogous evidence for an underlying /t/ in the word [ˈæɾm̩ ] atom, since, again, the alveolar consonant in this root may either appear as[ th ] or [ɾ], depending on the phonetic context where the segment appears. Flapping only takes place before an unstressed vowel, and thus in /ætm̩ / the consonant /t/ is pronounced as [ɾ]; but in the related form [əˈt h amɪk] where stress has shifted to the second syllable of the root, we can see that the underlying /t/ surfaces phonetically (as an aspirate, following the previously discussed rule of aspiration).

We may state the rule of flapping as follows: “an alveolar stop becomes a flap when it is followed by an unstressed syllabic and is preceded by a vowel or glide.” You will see how vowels and glides are unified in the next chapter: for the moment, we use the term vocoid to refer to the phonetic class of vowels and glides. It is again important to note that the notion of “vowel” used in this rule must include syllabic sonorants such as [ɹ̩] for the preceding segment, and [ɹ̩] or [m̩ ] for the following segment. The rule is formalized in (9).

Flapping is not limited to the voiceless alveolar stop /t/: underlying /d/ also becomes [ɾ] in this same context.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة