Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The present approach

المؤلف:

Bernd Heine and Tania Kuteva

المصدر:

The Genesis of Grammar

الجزء والصفحة:

P20-C1

2026-02-20

29

The present approach

The procedure of reconstruction adopted here is the one summarized in (4).

(4) Reconstructing language evolution

a. X and Y are phenomena that are related in some way.

b. Hypothesis 1: X existed prior to Y.

c. Hypothesis 2: There was a change X>Y (but X continues to exist parallel to Y).

d. There is evidence in support of (4c).

e. There are specific factors that explain (4c).

Examples (4a) through (4c) are in some form or other part of many approaches in the historical sciences. As has been demonstrated by Botha (2003a), (4d) is the most controversial component in studies on language evolution, but it is also the most crucial one. The factors that have been invoked to deal with (4e) have in many cases been taken from evolutionary biology, relating in particular to notions such as natural selection, adaptation, exaptation, mutation, etc. (see “Previous work”). For example, in their seminal paper on language evolution, Pinker and Bloom (1990) see adaptation by natural selection as the special factor of (4e):

Language shows signs of complex design for the communication of propositional structures, and the only explanation for the origin of organs with complex design is the process of natural selection. (Pinker and Bloom 1990: 726)

As we noted in “Previous work”, however, the way these biological notions have been employed in studies on language evolution leaves a number of questions unanswered—we are not aware of any convincing way to account for natural selection in language evolution.

Over the past decades, the study of language genesis has been approached from a wide range of different angles and disciplines, many of which are not primarily linguistic in orientation. The approach used here on the basis of (4), that is grammaticalization theory, is linguistic in nature. It relies on regularities in the development of linguistic forms and constructions. Heine and Kuteva (2002b) claim that it is possible to push linguistic reconstruction back to earlier phases of linguistic evolution by using this theory. The purpose here is to substantiate the claim made there by providing a wider range of crosslinguistic evidence, to propose a framework for reconstructing grammar and to relate this framework to some of the issues on early language that have been raised over the last decades.

We may illustrate this approach with an example from English. In the sentences of (5) there are two instances of the item used: In (5a), it has the function of a physical action verb, that is, of a lexical verb, while in (5b) it serves as an auxiliary verb expressing the aspectual notion of past habitual action.1

(5) English

a. He used all the money.

b. He used to come on Tuesdays.

From the history of English, we know that the lexical use of used as in (5a) is older than the auxiliary used in (5b), and that the latter has in some way developed historically out of the former, in accordance with (4a) through (4c). This means that at some earlier stage in the history of English there was a lexical item use but no habitual marker used to.

That this is not an isolated case can be shown with two more examples, (6) and (7): In the (a)-sentences, kept and is going have the function of action verbs while in the (b)-sentences they serve as auxiliaries expressing aspect or tense functions: in the case of kept this is a durative aspect, and in the case of is going that of a future tense. Furthermore, as the history of the English language tells us, the (a)-uses of these items existed before the (b)-uses, and the latter can be traced back to the former, once again in accordance with the reconstruction model in (4).

(6) English

a. He kept the money.

b. He kept complaining.

(7) English

a. He is going to town.

b. He is going to come soon.

Such examples are not restricted to English; example (8) from French is strikingly similar to the English example (7): Both have a motion verb ‘go’ in (a), and in (b) there is a homophonous item denoting future tense, and in both cases, (b) can be shown to be historically derived from (a).

(8) French

a. Il va a̒ la maison.

he goes to the house

‘He’s going home.’

b. Il va venir bientôt.

he goes to.come soon

‘He is going to come soon.’

But it is not only English and French that exhibit such examples; more examples can be found in hundreds of genetically unrelated languages2 all over the world (see especially Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994; Heine 1993; Kuteva 2001; see also “Treating events like objects” (b)), exhibiting the properties mentioned above as well as a number of others. A list of such properties is found in (9).3

(9) Generalizations

a. There are two homophonous items A and B in language L, where A serves as a lexical verb and B as an auxiliary marking grammatical functions such as tense, aspect, or modality.

b. While A has a noun as the nucleus of its complement, B has a non-finite verb instead.

c. While A is typically (though not necessarily) an action verb, B is an auxiliary expressing concepts of tense, aspect, or modality.

d. B is historically derived from A.4

e. The process from A to B is unidirectional; that is, it is unlikely that there is a language where A is derived from B.

f. In accordance with (9d) and (9e), there was an earlier situation in language L where there was A but not B.

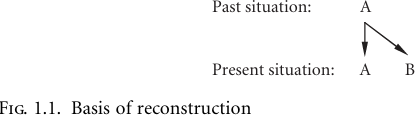

While properties (9a) through (9c) specifically refer to the data presented in the preceding examples, (9d) through (9f) are central to grammaticalization theory in general, and of the methodology used here in particular: They allow us to use a technique of linguistic reconstruction using the situation depicted in Figure 1.1 as a basis. In accordance with this technique, we will say that given a present situation where there are phenomena A and B, such as the ones presented in (9a–9e), we hypothesize that (9f) applies.

With reference to our English example in (5), (6), and (7) this means that in Modern English there are functional categories, exemplified by used to, keep V-ing, and be going to, that were not there at some earlier stage in the history of English, and that it is possible to reconstruct such an earlier stage on the basis of (9) even in the absence of any historical evidence.

This technique is not really new, it has been exploited in particular in another method of historical linguistics, namely that of internal reconstruction. However, unlike internal reconstruction, the technique as used here is not restricted to the analysis of language-internal processes; rather, it is comparative in nature and allows for reconstructions across languages 5 (see “Methodology”).

More relevant for our purposes are works where the technique has been recruited—implicitly or explicitly—to deal with earlier situations in language evolution (e.g. SankoV 1979; Comrie 1992; Aitchison 1996). Common to these works is the assumption that languages reveal layers of past changes in their present structure. Thus, Comrie (1992, 2002) argues that certain kinds of present linguistic alternation can be reconstructed back to earlier states without that alternation.6

This technique, and the methodology of which it is a part, will be described in “Grammaticalization”. In the spirit of the works just cited we will endeavor to apply it to stages in the development of human language that are not accessible to other methods of historical linguistics. Our reconstruction work will be based on the following observations:

(10) Observations underlying reconstruction

a. Grammaticalization theory offers a tool for reconstructing the rise and development of grammatical forms and constructions. It rests on generalizations about language change that happened in modern languages (see “Grammaticalization”).

b. There is no intrinsic reason to doubt that language change and the functional motivations underlying it were of the same kind in early language as what we observe in modern languages.7

c. Accordingly, grammaticalization theory can be extended from modern languages to early language by extrapolating from the known to the unknown.

d. Human language was structurally less complex at its earliest stage of evolution than modern languages are.

With the exception of (10a), which is supported by massive evidence, none of these observations is really unproblematic—they are bluntly speaking of the inferential-jump type. Statement (10b), and consequently also (10c), may be intuitively plausible and there does not appear to be any contradicting evidence, but there is no hard-core evidence in their support, either. And the same applies to (10d): While it echoes what has been claimed in much of the literature on language evolution within the last decades, there is no substantive evidence available to support it.

Another problem characterizing (10) is as follows: Whereas (10b) asserts sameness between early language and modern languages, (10d) maintains that there is a difference. That (10b) refers to ‘‘early language’’ and (10d) to the ‘‘earliest stage of evolution’’ does not solve this problem, since the latter is part of the former in accordance with our definition in “Previous work”. One may argue that there is a difference, in that (10b) concerns a process while (10d) concerns a state. Still, this would not be an entirely satisfactory solution either; we will return to this issue in “On uniformitarianism”.

Statement (10b) rests on the observation that the motivations under lying language use are cross linguistically essentially the same, and that at any stage in the development of languages, the same processes of change were at work. For example, we observe that in modern languages there is a widespread phonetic change from plosive to fricative consonants (e.g. from p to f), from voiceless to voiced intervocalic consonants, or a morphosyntactic change from lexical verb to auxiliary, while a change in the opposite direction is clearly less likely. Accordingly, we argue that this justifies the assumption that such changes were also possible in early language. Recent research has shown that grammaticalization is regular across different kinds of linguistic communication systems, including signed languages (Janzen 1995, 1998, 1999; Janzen and Shaffer 2002; Sexton 1999; Wilbur 1999; Pfau 2004; Pfau and Steinbach 2005a, 2005b; Shaffer 2000), pidgin languages, as well as in situations of language contact (Heine and Kuteva 2003, 2005, 2006). Thus, we argue that hypotheses on language evolution that do not take (10b) into account (i.e. generalizations on diachronic processes to be observed in modern languages) are empirically less plausible, and we will ignore such hypotheses in the remainder of this work.

For example, there is little evidence in attested morphosyntactic changes for hypotheses that have been proposed on the basis of what may be called the holistic (or analytic) hypothesis: On this hypothesis, early language was characterized by holistic, monomorphemic linguistic signals conveying propositional contents,8 and these signals are believed to have undergone a segmentation process whereby complex but unanalyzable signals were broken down into words and syntactic structures (Wray 1998, 2000; Kirby 2002; Arbib 2005: 119). While we concur with the proponents of this hypothesis (e.g. Callanan 2006) that pragmatics is a crucial factor in language change, we are not aware of any diachronic evidence to the effect that such a segmentation process can commonly be found in language change: New grammatical categories do not normally arise via the reinterpretation of complex, unanalyzed propositions; accordingly, we consider this hypothesis to be less convincing for reconstructing language evolution (see “Layers”).

To be sure, it may happen that unanalyzable lexemes, such as Watergate, Hamburger, or lemonade in English, are segmented and give rise to new productive morphemes (-gate,-burger, ade), and folk etymology also pro vides examples to show that segmentation is a valid process of linguistic behavior. But such a process is, first, fairly rare (i.e. statistically negligible) and, second, it lacks the kind of regularity to be found in grammaticalization processes. Looking at the history of functional categories in English or other Indo-European languages it is hard to find grammatical elements that arose via segmentation of holistic expressions, while there is an abundance of examples of grammaticalization. Furthermore, the rise of new lexemes via compounding is a highly productive process in English and many other languages, while there does not appear to be a productive process in any language whereby mono-morphemic lexemes are split up into two or more new lexemes.9 On account of such diachronic observations we side with Tallerman (2007) in assuming that the holistic hypothesis does not provide a convincing basis for reconstructing linguistic evolution.

In a similar fashion there are a number of other stimulating hypotheses that (10b) will prevent us doing justice to. One of them concerns what may be called in short the phonology-to-syntax hypothesis, which has been proposed to account for the rise of syntax: On this hypothesis, it was the neural organization underlying syllable structure, or phonology, that was co-opted to provide the syntax for strings of words (Lieberman 1984, 1998; Carstairs-McCarthy 1999: 147–8). As far as we are aware, there is no substantial evidence for this hypothesis in the history of modern languages, hence we will also ignore this hypothesis in the present work (for other problems with this hypothesis, see Bickerton 2005).

And much the same applies to hypotheses that invoke extra-linguistic forms of human behavior to account for language evolution, in particular the ‘‘Singing-Neanderthals’’ hypothesis, according to which there was a co-evolution of language and music (Mithen 2005). On this view, language evolved as a communication system distinct from music fairly late, at the Homo sapiens stage some 200,000 years ago, when language specialized in the transmission of information and music turned into a communication system for the expression of emotion. While there are in fact a number of interesting parallels shared by language and music, there is no convincing evidence to show that language change was affected by or can be related to musical behavior.

Circumstantial evidence for (10d) can be seen in the following observations: (a) As has been argued for by many authors on this subject, human language is the result of a direct transition from conceptualization and communication patterns of pre-human primates. It therefore must have passed through a stage where it was less complex than it is today (cf. Hurford 2003: 45, 49). (b) For good reasons, historical linguists tend to hold a ‘‘uniformitarian’’ position, according to which languages, as far back as they are recoverable via the methodology of historical linguistics, do not differ essentially in their degree of complexity. Still, there is at least some rudimentary evidence for a ‘‘non-uniformitarian’’ view according to which modern language was not always as complex as it is now; we will return to this issue in “On uniformitarianism”.

As the remarks just made suggest, the observations in (10) do not all have the same empirical status. Pinker and Bloom (1990) draw a distinction between two notions which are crucial for our approach: testability in-principle and testability-in-practice (see Botha 2003a: 122):

(11) Two ways of testing a theory

a. A theory (or hypothesis) is testable-in-practice if (a) it is testable in-principle and (b) empirical data are in fact available with which its test-implications can be confronted.

b. A theory (or hypothesis) is testable-in-principle if (a) precise test-implications can be derived from it and (b) the empirical data can be specified which, if they are available, would indicate that the test-implications are false.

On the basis of this distinction, we can say that observation (10a) is in accordance with (11a), in that grammaticalization theory is testable-in practice: It rests on generalizations on linguistic change which is immediately accessible and hence can be verified or falsified. But the remaining observations (10b) through (10d) are not: They concern hypotheses on early language, which is not immediately accessible in terms of historical analysis. It is possible to specify the kind of empirical data that, if they should become available, would indicate that the test implications can be falsified, but these hypotheses are not testable in practice.

Since the ‘‘inferential jump’’ from modern languages to early language that we alluded to above is not testable-in-practice, we require a hypothesis (or theory) responding to (11b)—one which licences inferential jumps on the relationship between two distinct phenomena, or, in other words, one which relates phenomena belonging to different onto logical domains (namely those of modern languages and of early language) to one another in a principled way—that is, we need a bridge hypothesis. Following Both a (2003a:147) we will say that such a hypothesis consists of an internally coherent set of assumptions which explicitly interlinks properties of entities of one onto logical domain with properties of entities of another onto logical domain. The hypothesis that we use rests on the observations proposed in (10).

In accordance with this hypothesis, the evidence that we will rely on is of a specific kind: It is based on observations made on the development of modern languages and our methodology rests exclusively on such observations. In other words, we will ignore observations that are not immediately accessible via this methodology. Underlying this methodology there is observation (10b) in that, with regard to language change, human behavior was essentially the same at the stage when early language arose as it can be observed to be today.

1 We are ignoring here the fact that the two useds are phonetically distinct, viz. [juzd] in (5a) vs. [just] in (5b) (Philip Baker, p.c.). This difference is a largely predictable product of the grammaticalization parameter of erosion, as we will see in “Erosion”. Furthermore, we are also ignoring the fact that there were various intermediate stages in the processes sketched here.

2 The expression ‘‘genetically unrelated languages’’ must be taken with care; it is a shorthand for ‘‘languages which so far have not been proven to be genetically related.’’

3 Our reconstruction is based on attested cases of grammatical change, where we have written records and where these generalizations seem to hold. So we assume that these generalizations can be used for reconstructing cases where written records are missing.

4 This generalization is in need of qualification. It hypothesizes a process from A to B that happened at some stage in the past, but it is possible that A is no longer exactly what it used to be at that stage.

5 An argumentation that is in line with the present approach is found in some of Greenberg’s works (Greenberg 1992: 154; see also Croft 1991).

6 It might be argued that this approach works in cases where appropriate historical evidence exists, but not necessarily in other cases. In other words, our claim that the presence of two structures A and B can be traced back to an earlier situation where there was A but no B cannot be generalized. It is a common analytic procedure, we argue, to describe the unknown in terms of the known given appropriate correlations between the two, and not much would be gained by rejecting such a generalization.

7 In the wording of Comrie (2002:256): ‘‘We propose no processes that are not attested in the historical period.’’ We will return to this issue in “On uniformitarianism”.

8 ‘‘From the viewpoint of present-day languages, every sentence of this early language would be fully suppletive’’ (Comrie 2002: 253).

9 An anonymous reader points out that there are processes such as that from expressions for one-word utterances (e.g. German ja!, doch!, schon!) to modal particles (Waltereit 2001), which can be taken to lend support to the holistic hypothesis. While this is in fact a semantic process involving grammaticalization, it does not relate to what appears to be at the core of this hypothesis, namely that there is a segmentation process whereby complex but unanalyzable signals are broken down into words and syntactic structures. We do not wish to exclude the possibility that there may have been a holistic stage preceding early language, but those phases of language evolution that are accessible via grammaticalization theory are not really compatible with this hypothesis.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)