Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

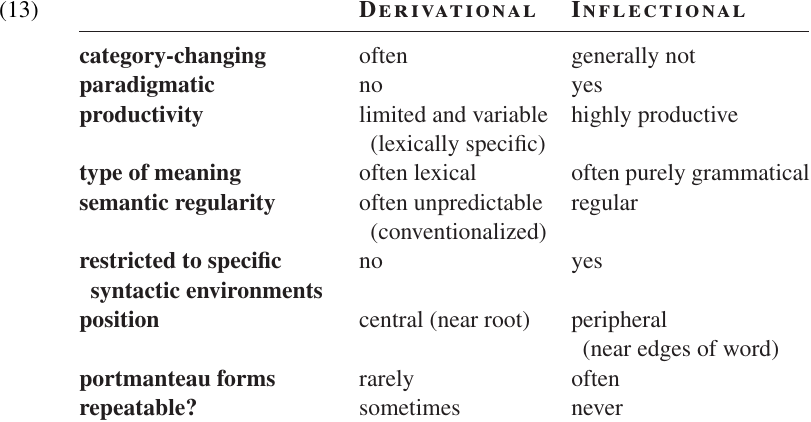

Criteria for distinguishing inflection vs. derivation

المؤلف:

PAUL R. KROEGER

المصدر:

Analyzing Grammar An Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

P250-C13

2026-01-28

22

Criteria for distinguishing inflection vs. derivation

At the beginning, we introduced the contrast between inflection vs. derivation by saying that derivational morphology changes one lexeme into another, while inflectional morphology creates different forms of the same lexeme. This statement captures the basic intuition behind these terms. However, it is not very useful as a definition unless we have a reliable way to determine whether two words which contain the same root are different lexemes or merely different forms of the same lexeme. If we do not have any independent criteria to guide us in making this judgment, the definition becomes circular.

In order to escape this circularity, let us adopt a different approach. We start with the notion of a STEM. The stem of a word consists of its root(s) together with all of the derivational affixes which it contains, but no inflectional affixes. As suggested above, we can say that two words are forms of the same lexeme just in case they share the same stem.

Under this approach, the terms STEM and LEXEME will be well-defined if we have some independent way to distinguish inflection from derivation. We must point out at once that this can be a very difficult task, because certain affixes do not fit neatly into either classification. Some scholars deny that it is possible to make such a distinction at all. We can, however, identify a number of properties which are typical of inflectional morphology and others which are typical of derivational morphology, as these terms have traditionally been used. These properties allow us to describe the distinction between inflection and derivation in terms of a contrast between two PROTOTYPES. Most affixes in most languages can be assigned to one class or the other according to which prototype they share the most properties with.

Here are some of the properties which define the two prototypes:1

a Derivational morphology may change the syntactic category (part of speech) of a word, since it actually creates a new lexical item. Inflectional morphology, however, does not generally change syntactic categories.2 As we noted above, the derivational suffix-able changes the verb believe into the adjective believable, whereas the inflected forms believes and believed are still verbs.

b Derivational morphology tends to have “lexical” semantic content, i.e. meanings similar to the meanings of independent words (X-er: ‘person who Xes’; X-able: ‘able to be Xed’; etc.). Inflectional morphology, on the other hand, often has purely grammatical meaning (plural number, past tense, etc.).

c Inflectional morphology is semantically regular; for example, the plural-s in English always means plural number. Derivational morphology may have variable semantic content which depends on the specific base form: a sing-er is a person who sings, a cook-er is an instrument which cooks things, a speak-er could be either the per son who speaks or a device for amplifying his voice, and a hang-er is a hook or other device to hang things on.

d Inflectional morphology may be, and often is, syntactically determined; but this is not true of derivational morphology.3 Therefore, if a particular morphological marking is required or allowed only in specific syntactic environments, it is likely to be inflectional. For example, present tense verbs in English must agree with their subject for person and number. The suffix which marks this agreement (-s) is inflectional because it must occur in certain syntactic environments (e.g. 7b) and must not occur in others (e.g. 7a).

(7) 3rd singular present–s:

a *We all likes Mary a lot.

b *John like Mary too.

English is rich in derivational morphology, but has relatively few inflectional categories. Some additional examples include the plural (-s) on nouns and the two participial forms of verbs (-ing and-en). In both cases, there are certain syntactic contexts where the inflected form is required (8a, 9a), and others where it is not allowed (8b, 9b).

(8) Pural–s:

a *My three cat are sick.

b *This cats is really sick.

(9) Past participle–en:

a *John has eat my sandwich.

b *The tiger eaten John before we could save him.

On the other hand, there is no syntactic environment that requires an adjective ending in-able. Words containing this suffix may occur in the same positions as any other adjective, as illustrated in (10). This is exactly what we would expect, based on our earlier conclusion that-able is a derivational affix.

(10) a Forsythe’s latest novel is very good/long/readable.

b Mary’s silly/wild/unbelievable story failed to convince her mother.

Inflectional morphology is normally highly PRODUCTIVE, meaning that it applies to most or all of the words of the appropriate category. Derivational morphology, on the other hand, often applies only to certain specific words; and some derivational affixes are more productive than others.

When we speak of “productivity” in this sense, we are thinking of grammatical and semantic patterning rather than phonological regularity. For example, virtually every verb in English can be inflected for past tense. However, there are many different phonological processes that can be used to mark this inflectional category:

(11) bake baked

stretch stretched

catch caught

buy bought

think thought

drink drank

sing sang

run ran

go went

is was

hit hit

Thus, past tense is productive but not phonologically regular. Contrast this situation with the case of a derivational affix like-ize. This suffix is actually quite productive in English, being used in many new words (e.g. digit-ize, Vietnam-iz-ation). But, even so, there are numerous nouns and adjectives which cannot take this suffix. For example, we can rubberize something by coating it in rubber; but when we coat something in chocolate or sugar, we do not say *chocolatize or *sugarize. Similarly, we say hospitalize but not *prison-ize (cf. im-prison); legalize, formalize, publicize, privatize, etc., but not *good-ize (for ‘improve’) or *big-ize (for ‘enlarge’).

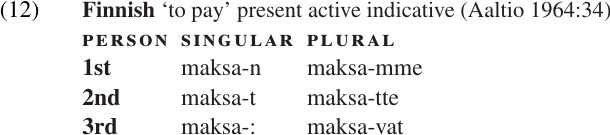

Inflectional morphology is often organized in paradigms, while derivational morphology is not. A PARADIGM can be defined as a set of forms which includes all of the possible values for a particular grammatical feature. For example, the table in (12) illustrates the subject-agreement paradigm in Finnish. The six verb forms in the table differ only in the categories of person and number; the categories of tense, voice, and mood remain constant. There is one suffix representing each possible combination of person and number, and no verb contains more than one of these suffixes. This illustrates the general principle that affixes which belong to the same paradigm are (normally) mutually exclusive (i.e. they cannot co-occur).

Portmanteau morphemes (i.e. single affixes which mark two or more grammatical categories at once, like the Finnish person-number suffixes in (12)) typically involve inflectional categories. Derivation is rarely marked by portmanteau forms.

Inflectional affixes are normally attached “outside” (i.e. further from the root than) derivational affixes, as in: class-ify-er-s; nation al-ize-d̳.

Some derivational processes may apply twice in the same word, but each inflectional category will be marked only once.

1. This discussion is based on Bickford (1998:114–116,138–140); Stump (1998:14ff.); and Aronoff (1976:2).

2. This principle is challenged by Haspelmath (1996), who identifies constructions such as gerunds and participles as examples of “category-changing inflection.” He also points out that this kind of morphology creates “mixed categories.” Gerunds, for example, select the same kinds of dependents as the verbs they are based on, but the phrases which they head have the external distribution of NPs rather than VPs. See also Bresnan (1997); Bybee (1985:85).

3. Anderson (1982), Bickford (1998), and some other authors take this characteristic to be the principle defining feature of inflectional morphology.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)