Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Online Pragmatics and Intercultural Communication courses

المؤلف:

Winnie Cheng & Martin Warren

المصدر:

Enhancing Teaching and Learning through Assessment

الجزء والصفحة:

P201-C18

2025-07-05

751

Online Pragmatics and Intercultural Communication courses

A number of concepts served as the guiding principles when OCLA was incorporated into the design of the subject syllabuses. Reading and learning from materials online and doing assessed tasks online, compared to attending lectures and interacting with the lecturer, require a much higher level of independence in learning. Online learning therefore puts a greater demand on students regarding their cognitive, motivational and interpersonal abilities for learning. Assessment procedures and methods were also re-designed to better reflect the course aims, objectives, pedagogy and learning outcomes.

In addition, the peculiarities and uniqueness of web-based learning should be maximally exploited. The increased interactivity afforded by online learning and teaching makes online collaborative assessment feasible (MacDonald et al., 2002). MacDonald et al. (2002, p.10) review a number of sub-projects which have practiced collaborative formative evaluation of learning and teaching, including peer review of students' scripts posted electronically (Davis & Berrow, 1998); model answers delivered to help students to see alternative approaches to written work (Mason, 1995); process writing of assignments or 'iterative assignment development' (McConnell, 1999); and students involved in online negotiation of assessment criteria (Kwok & Ma, 1999).

Group work and involving students in the assessment procedures are also important. The value of group work as a means to developing skills such as "communication, presentation, problem-solving, leadership, delegation and organization" (Butcher et al., 1995, p.165) is well established. The problem in an assessed course in which group work takes place is that the teacher needs to assign individual grades to the students rather than the same grade for every member of the group. In order to fairly measure individual students' performance in the group work, the contribution of the individual to the group project will be established. One possible way to deal with this potential dilemma is to introduce an element of peer assessment to determine the contribution of individuals to a group project (Conway et al., 1993; Cheng & Warren, 1999). In this study, peer assessment refers to a system of assessment whereby students, through online discussion and negotiation, assess the peers' contribution to both the conduct and the outcome of group work. In addition to peer assessment, students perform self-assessment of their own contribution to the collaborative project, and the teacher assesses student effort in group projects shown in online feedback and discussion of the feedback.

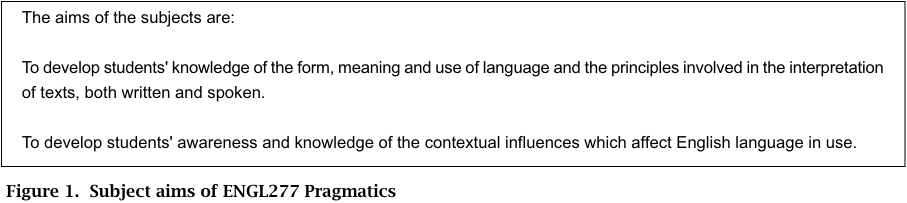

Bearing in mind the issues and guiding principles discussed above, the syllabuses of the subjects Pragmatics and Intercultural Communication were written to incorporate OCLA in their aims, learning outcomes and assessment. Figure 1 shows the subject aims of ENGL277 Pragmatics.

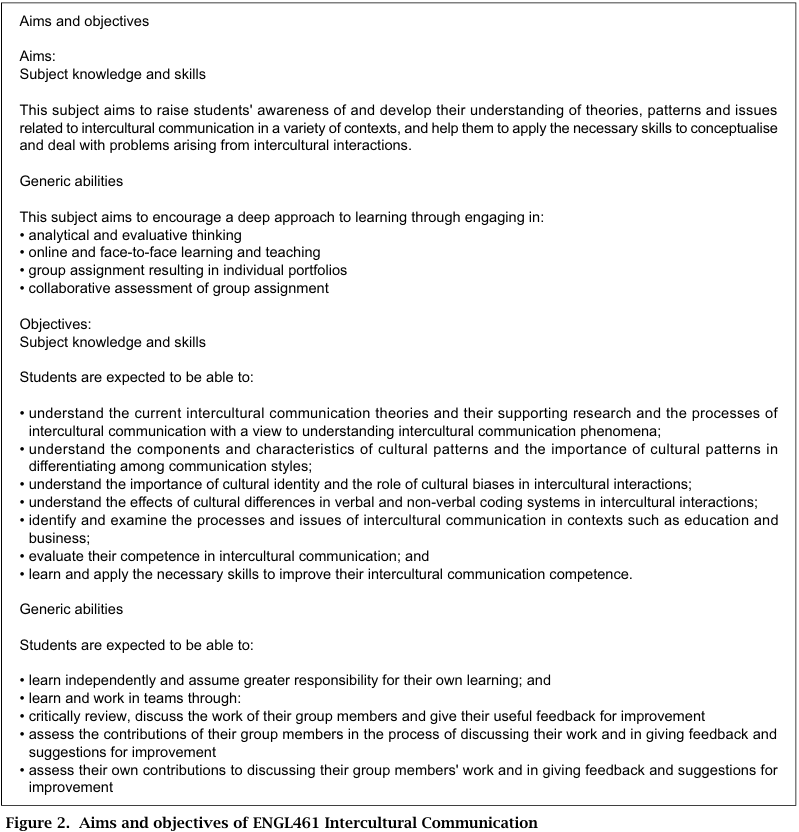

Figure 2 shows the more detailed subject aims and objectives in the syllabus of ENGL461 Intercultural Communication, which shows that both acquisition of subject knowledge and development of generic attributes are emphasized.

Online delivery of Pragmatics and Intercultural Communication made use of the combination of computers and network technology, asynchronous group and individual messaging, and the real-time interactive features of the World Wide Web. Traditional face-to-face lecturing in two-hour slots was replaced by students' online study; the lectures were presented by means of online learning materials using the WebCT platform. All teaching materials (notes, exercises, examples and audio clips) were uploaded on the subject Website. Weston and Barker (2001) summarize the major reasons for using online learning materials: the shortening of distance between student and place of learning, ease of access to resources, interactivity and multimedia, student control of learning, and distributed communication or collaboration. Compared to attending two-hour lecture sessions, when learning the subject materials online, students could do things like repeating or changing the sequence of units, and manipulating and rewinding video and audio clips that formed part of the online learning materials. Built into the learning units were discussion forums on the WebCT which allowed students to respond to each other and the teacher, giving them the opportunity to revise and reflect upon their work and to engage in reflective discussion (Bonk & King, 1998; Brown et al., 2000).

There were weekly one-hour seminars with groups of 20-25 students, whereby the concepts learnt through the online materials were consolidated through applying them to seminar activities. From the outset, it was made clear to the students that the weekly seminar must not be turned into a kind of 'WebCT user' discussion group, and that any problems or suggestions for the online learning should be discussed on the WebCT, or e-mail messages, in an office visit or by telephone.

In the first lesson, the rationale, procedure, instructional materials, teaching and learning activities, assessments and evaluation were explained to the students. The students were told that online learning means taking greater responsibility for their learning, experiencing a higher level of interactivity than attending lectures, and adjusting to greater flexibility and control in terms of when and how they learn. It was emphasized that in order to make the most of this new development, it was important that the students should approach it positively and enthusiastically, and that both their learning process and product would be closely monitored and fully evaluated.

الاكثر قراءة في Teaching Strategies

الاكثر قراءة في Teaching Strategies

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)