تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

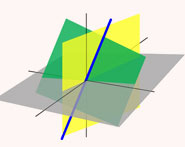

الهندسة

الهندسة

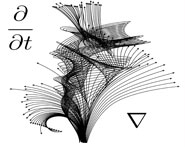

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 21-2-2018

Date: 21-2-2018

Date: 20-2-2018

|

Born: 15 October 1927 in Waldheim, Germany

Died: 26 April 2011 in Leipzig, Germany

Hans Wussing's father was a business employee. After studying at primary school for three years, Hans began his secondary school education where he soon developed a great interest in chemistry, physics and mathematics. However, even before he was twelve years old, war had broken out. He continued his secondary education until January 1943 when Germany began the Luftwaffenhelfer programme. This drafted all boys born in 1926 or 1927, which included Wussing, into the military where they were supervised by the Hitler youth who began a programme of ideological indoctrination. Members of the Luftwaffe also trained the boys in military duties. In 1944, when he reached the age of 17, Wussing was drafted into the German army and sent to Belgium. There he was captured by the advancing British forces. Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze writes in [14]:-

After being prisoner of war under the British in Belgium and under mournful circumstances, half frozen and half starved to death, Wussing reached his birthplace Waldheim in East German Saxony in 1946 and continued his school education.

In fact it was March 1946 when he arrived back in Waldheim and he returned to school, completing his secondary education in 1947. We should note that, as a consequence of his experiences during the war, Wussing had a deep hatred for war and Fascism for the rest of his life.

Perhaps one of the most surprising facts about Wussing is that he became a mathematician by mistake rather than by design. He applied to the Leipzig University to train as a secondary school teacher. His application requested that he take chemistry as his major subject with physics and mathematics as minor subjects. However, the university made an administrative error when dealing with his application and he was offered a place to study mathematics as his major subject. He felt so lucky to be offered a place at Leipzig University that he did not complain about the error and, on 17 October 1947, he began studying mathematics as his main topic with physics as his minor subject. However, he had broad interests and, while at university he continued his interests in historical, philosophical, cultural and social issues [4]:-

Politically, he was committed to building a better, more socially just and peaceful society.

While he was studying at Leipzig University, Wussing met his fellow student Gerlinde Walter. She, like Wussing, had completed her secondary education in 1947 and, again like him, was studying a course at Leipzig University to qualify as a secondary school mathematics teacher. Both of Gerlinde's parents were school teachers. In 1951 Hans and Gerlinde took the state examination and they qualified as high school teachers of mathematics and physics. During the time they had been studying at university the process of creating two Germanys had been going on. In East Germany the Socialist Unity Party swept to power. Both Hans and Gerlinde had joined this Party in June 1947, a year after its formation in April 1946. Hans and Gerlinde married in 1952. By this time Wussing was undertaking research towards his doctorate in group theory advised by Walter Schnee while his wife was teaching in the Workers and Peasants Faculty of the University which had been set up to assist children from disadvantaged backgrounds gain access to studying academic subjects. Hans and Gerlinde Wussing's daughter Petra was born in 1953. When Petra, who became a biochemist, was a child she [14]:-

... took a considerable part of the couple's energy. Hans helped in looking after their only child. The bulk of housework, however, he left in traditional manner to his wife.

Wussing completed his doctoral studies and was awarded a doctorate for his thesis Über Einbettungen endlicher Gruppen in 1957. During the previous two years, 1955-57, he had been teaching at Leipzig University and the delay in obtaining his doctorate is explained in [14]:-

He could not defend his dissertation until 1957 because he had to read it regularly to his advisor, the almost blind Walter Schnee (1885-1958).

The direction that Wussing's career would take after 1957 was less than clear. He considered becoming an industrial mathematician in the aeronautic industry but, despite the attractions, particularly in terms of salary, of such a position he decided against following that route. By a fortunate turn of events another possibility opened up. The head of the Workers and Peasants Faculty where Wussing's wife was teaching, and in which Wussing himself had taught for two years, was Annemarie Harig, the sister of Gerhard Harig (1902-1966). Through her Wussing learnt that Gerhard Harig was about to take over as head of the Karl Sudhoff Institute at Leipzig University and that he aimed to make it an Institute, which had previously only covered the history of medicine, into the Karl Sudhoff Institute for the History of Medicine and Science. Harig was looking to appoint staff in the area of the history of mathematics and science to the Institute and although Wussing was not qualified as a historian of science, nevertheless he was a member of the Socialist Unity Party which was highly influential at the university. Both Harig and Wussing shared beliefs in a Marxist philosophy which strongly influenced their writing.

Wussing was appointed as an assistant at the Karl Sudhoff Institute in 1957 and began working on his habilitation thesis on the history of mathematics. His habilitation thesis Die Genesis des abstrakten Gruppenbegriffes was completed in 1966. It was published in 1969 as a German book and was translated into English and published under the title The genesis of the abstract group concept. A contribution to the history of the origin of abstract group theory in 1984. Wussing explains in the Introduction his aims:-

The existence of two additional roots of abstract group theory has been obscured mainly by the fact that the group-theoretic modes of thought in number theory and geometry remained implicit until the end of the middle third of the nineteenth century; they made no use of the term 'group' and, in the beginning, had virtually no link to the contemporary development of the theory of permutation groups. [I seek] those paths of development of implicit group theory that have made a causal contribution to the rise of explicit group theory.

Bernhard Neumann writes in a review of the 1969 German edition:-

This is not, of course, a history of the development of group theory, though much of this development, approximately to the end of the 19th century, can be found in the book. The author has set out to trace the process of abstraction that led finally to the axiomatic formulation of the abstract notion of group. His main thesis, ably defended and well documented, is that the roots of the abstract notion of group do not lie, as frequently assumed, only in the theory of algebraic equations, but that they are also to be found in the geometry and the theory of numbers of the end of the 18th and the first half of the 19th centuries.

Following Harig's death in 1966, Wussing became acting director of the Karl Sudhoff Institute in 1967. In the following year he was appointed as an extraordinary professor of the history of mathematics and natural sciences at the University of Leipzig and in 1970 he became an ordinary professor. In 1977 he became director of the Karl Sudhoff Institute [16]:-

Hans Wussing became the teacher and advisor of most historians of mathematics who ever were working in this field from the late 1950s until the end of the German Democratic Republic. Following in the tradition of Gerhard Harig, Hans Wussing was one of the most important persons in the field history of mathematics and history of science in the German Democratic Republic and one of their representative in the international scientific community. From 1967 to 1987 he served as President of the National Committee on History of Science of the German Democratic Republic. From 1967 to1998 he was editor-in-chief of the well known journal NTM. In 1984 he became a Member of the Academy of Science of Saxonia, Leipzig.

We have already noted Wussing's Marxist beliefs. It is unclear whether this explains the fact that up to the end of the German Democratic Republic in 1990, Wussing never published in any Western journal although he was an editor of Historia Mathematica from 1974 to 1990. Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze writes [14]:-

Personally I regret that Wussing, who belonged to the editorial board of 'Historia Mathematica' from the beginning, without publishing a single paper in that journal, apparently never encouraged others to publish there either.

Wussing was, as mention in the quote above, an editor of NTM - Schriftenreihe für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften, Technik und Medizin (The Journal for the history of science, technology, and medicine) from 1967 and strongly supported this journal by publishing in it and encouraging his students to publish in this journal published in Leipzig.

Let us now look briefly at some of the books that Wussing has published. These include: (i) Nicolaus Copernicus (1973); (ii) Carl Friedrich Gauss (1974); (iii) Isaac Newton (1977); (iv) Course on the history of mathematics (1979); (v) Adam Ries (1989); (vi) From counting pebbles to the computer (1997); (vii)From Gauss to Poincaré (2009); (viii) From Leonardo da Vinci to Galileo Galilei (2010); and (ix) (with Menso Folkerts) From Pythagoras to Ptolemy (2012). As an illustration of Wussing's approach to the history of mathematics, we quote from a review of Nicolaus Copernicus (1973):-

One of the most useful features of this book is the author's (handsomely illustrated) description of the social, political, economic and scientific context in which the life and work of Copernicus must be set. Another is his description of the influence of Copernicus and of the work that has been done over the centuries in elucidating and assessing that influence. Thus, he has given a truly historical account, without, however, losing sight of the mathematical and astronomical details.

As an illustration of Wussing's own description of his aims in treating the history of mathematics, we quote from the Preface to 'Hans Wussing et al, Vom Zdhlstein zum Computer: Mathematik in der Geschichte. Volume 1: Uberblick und Biographien' (1997):-

Why study the history of mathematics when mathematics is such a dreaded subject for many students and most people only shudder when recalling classes and tests in mathematics? The mathematical historian Wussing gives a detailed answer to this question in the first chapter of this introduction: The occupation with the history of mathematics is an intellectual adventure, in which one can experience the suspense of how mathematics has evolved, how much hardship and error it took people from the first beginnings in the dim and distant past to erect - over the millennia - the magnificent mental structure whose contents and methods have become the foundation and indispensable apparatus for the development of all technology, the sciences, medicine, business and industry, and which, in the form of the computer, have practically embraced every aspect of modern life.

Catherine Goldstein writes in a review of this book:-

This textbook is the first volume of a projected series intended as a basic introduction to the history of mathematics and designed for independent study, in particular for students and high school teachers. ... The authors' goal is to present mathematics as a human adventure, tied to many aspects of cultural and social life. ... it is extremely rare to find a textbook that sheds light on the work of the historian, behind the narrative presentation of the mathematics. This emphasis, which is everywhere visible here, seems very useful, and I would recommend that it be adopted in other texts to help foster a more complete understanding of the history of science. ... the lively, clear, and simple style nicely conveys its main message: that mathematics is a human pursuit whose aims and motivations can be understood by everyone.

Wussing received many honours for his outstanding contributions to the history of mathematics. The most prestigious of these was the Kenneth O May Prize given for outstanding contributions to the history of mathematics. The first award of this prize was to Dirk Struik and Adolph Pavlovich Yushkevich at the 18th International Congress of History of Science in Hamburg and Munich in 1989. The second award was to Christoph Scriba and Hans Wussing at the 19th International Congress of History of Science in Zaragoza, Spain in 1993. However, [14]:-

Of all the honours he was most excited about the volume 'Amphora', a book with contributions by 36 prominent historians of mathematics from 10 countries, which was dedicated to his 65th birthday in 1992.

Among the other honours he received, we mention that he was elected a corresponding member of the International Academy of the History of Science in 1971, becoming a full member 10 years later. In 1984 he was elected a full member of the Saxon Academy of Sciences in Leipzig where he chaired the Commission for the History of Science.

Let us quote from [16] a description of Wussing's character written by one of his students:-

Hans Wussing was warm and sympathetic, always generous in his appreciation of others' achievements and unfailingly helpful to their aspirations. Those who knew him will sorely miss him, will never forget his support and his advice, the stories he told about the history of science and the history of mathematics past and present, and above all his energetic encouragement of research and collaboration. Those who had the good fortune to meet Hans Wussing, not only at scientific congresses and conferences, but also in small discussion groups and those, moreover, who had the good fortune to meet and talk to him privately, will never forget his great knowledge and intelligence, his sense of humor and his kindness.

Wussing retired in 1992 but continued to work on the history of science, in particular publishing works aimed at presenting the history of mathematics to non-experts. The Karl Sudhoff Institute, in which the history of mathematics had flourished under Wussing's leadership, changed after his retirement. It contained one professor, two docents, eight assistants and several doctoral students involved in the history of mathematics in 1989 but this area has now completely vanished from the Institute which today is only involved in the history of medicine. The change in emphasis at the Institute was a cause for sadness for Wussing over the final years of his life although he was encouraged by the successes of his students. He died following several years of battling against cancer. During these years when he steadily became less mobile he was able to continue his studies because of the support of his wife Gerlinde.

Articles:

|

|

|

|

للعاملين في الليل.. حيلة صحية تجنبكم خطر هذا النوع من العمل

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"ناسا" تحتفي برائد الفضاء السوفياتي يوري غاغارين

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|