تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

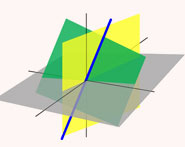

الهندسة

الهندسة

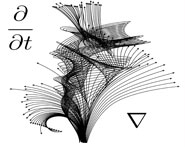

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 25-1-2018

Date: 17-1-2018

Date: 22-1-2018

|

Died: 16 October 1983 in Princeton, New Jersey, USA

Harish-Chandra's mother was Satyagati Seth, who was the daughter of the lawyer Ram Sanehi Seth, and his father was Chandrakishore who was a civil engineer. Chandrakishore had been educated at the Thomason Engineering College at Roorkee, then entered the Indian Service of Engineers and the first part of his career was [14]:-

... spent in the field, usually on horseback, inspecting and maintaining the dikes of the extensive network of canals in the northern plains.

Since Harish-Chandra's father spent most of his time travelling around the country inspecting canals, Harish-Chandra spent most of his childhood living in his maternal grandfather's home in Kanpur. Ram Sanehi Seth was a wealthy man with a large house which was home to many of his relatives. Harish-Chandra, despite being a rather weakly child, did sometimes spend time travelling with his father. His education was treated by the family as of the utmost importance [14]:-

A tutor was hired, and there were visits from a dancing master and a music master. At the age of nine he was enrolled, younger than his schoolmates, in the seventh class. He completed Christ Church High School at fourteen, and remained in Kanpur for intermediate college, which he finished at sixteen ...

He then attended the University of Allahabad. Here he studied theoretical physics, this direction being the result of reading Principles of Quantum Mechanics by Dirac which he found himself in the university library. He was awarded a B.Sc. in 1941, then a master's degree in 1943. Harish-Chandra worked as a postgraduate research fellow on problems in theoretical physics under Homi Bhabha, at the Indian Institute of Science at Bangalore in Southern India. Bhabha had been a student of Dirac in the 1930s. Harish-Chandra began publishing papers on theoretical physics while at Bangalore, and he published a couple of joint papers with Bhabha extending some of Dirac's results. For the first six months he spent in Bangalore he lived with Dr Kale, a botanist from Allahabad, and his wife who had taught Harish-Chandra French when he was an undergraduate. The Kales had a daughter Lalitha who at this time was a young girl, but about eight years later in 1952 he returned from the United States to India and there married Lalitha.

Bhabha and Harish-Chandra's teacher, K S Krishnan at Allahabad University, recommended him to Dirac for research work at Cambridge which would lead to Ph.D. degree. In 1945 Harish-Chandra went to Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, where he studied for his doctorate under Dirac's supervision. However Harish-Chandra saw comparatively little of his supervisor, giving up attending Dirac's lecture course when he realised that Dirac was essentially reading from one of his books. He wrote that Dirac was (see for example [14]):-

... very gentle and kind and yet rather aloof and distant. ... [I decided] I should not bother him too much and went to see him about once each term.

During his time in Cambridge he began to move away from physics and became more interested in mathematics attending the lecture courses of Littlewood and Hall. He also attended a lecture by Pauli and pointed out a mistake in Pauli's work. The two were to become life long friends. Harish-Chandra obtained his degree in 1947 for his thesis Infinite irreducible representations of the Lorentz group in which he gives a complete classification of the irreducible unitary representations of SL(2,C).

Dirac visited Princeton for the year 1947-48 and Harish-Chandra went to the United States with him, working as his assistant during this time. However he was greatly influenced by the leading mathematicians Weyl, Artin and Chevalley who were working there. It was during this year in Princeton that he finally decided that he was a mathematician and not a physicist. He later wrote (see for example [14]):-

Soon after coming to Princeton I became aware that my work on the Lorentz group was based on somewhat shaky arguments. I had naively manipulated unbounded operators without paying any attention to their domains of definition. I once complained to Dirac about the fact that my proofs were not rigorous and he replied, "I am not interested in proofs but only in what nature does." This remark confirmed my growing conviction that I did not have the mysterious sixth sense which one needs in order to succeed in physics and I soon decided to move over to mathematics.

After Dirac returned to Cambridge, Harish-Chandra remained at Princeton for a second year. He spent 1949-50 at Harvard where he was influenced by Zariski. The period 1950 to 1963, spent at Columbia University, New York, was his most productive. During this time he worked on representations of semisimple Lie groups. Also during this period he had close contact with Weil. When we say that he spent the years 1950-63 at Columbia University we really mean that he was on the faculty there for this period, but it is fair to say that he spent long periods in other institutions. He spent 1952-53 at the Tata Institute in Bombay and it was during this year that he married Lalitha Kale (often known as Lily); they had two daughters [14]:-

Lily ... with good spirits, generous affection, patience, and all-round competence was to pamper him for thirty years.

He spent 1955-56 at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, 1957-58 as a Guggenheim Fellow in Paris where he was able to work with Weil and the two often went walking together. He was a Sloan Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study from 1961 to 1963.

In [14] Harish-Chandra is quoted as saying that he believed that his lack of background in mathematics was in a way responsible for the novelty of his work:-

I have often pondered over the roles of knowledge or experience, on the one hand, and imagination or intuition, on the other, in the process of discovery. I believe that there is a certain fundamental conflict between the two, and knowledge, by advocating caution, tends to inhibit the flight of imagination. Therefore, a certain naiveté, unburdened by conventional wisdom, can sometimes be a positive asset.

Armand Borel describes some of Harish-Chandra's contributions in [6]. Schwermer reviews that work as well as [25] and what follows is taken from these reviews:-

The impression one has of Harish-Chandra's work as a whole is one of surprising cohesiveness and uniformity. His primary interests revolved about the representation theory of reductive groups and harmonic analysis on these groups and their related homogeneous spaces. However Harish-Chandra made several attempts to get into algebraic geometry or number theory.

He has built a fundamental theory of representations of Lie groups and Lie algebras, respectively of harmonic analysis on these groups and their homogeneous spaces. It was Harish-Chandra who extended the concept of a character of finite-dimensional representations of semisimple Lie groups to the case of infinite-dimensional representations; he proved an analogue of Weyl's character formula.

Some major contributions by Harish-Chandra's work may be singled out: the explicit determination of the Plancherel measure for semisimple groups, the determination of the discrete series representations, his results on Eisenstein series and in the theory of automorphic forms, his "philosophy of cusp forms", as he called it, as a guiding principle to have a common view of certain phenomena in the representation theory of reductive groups in a rather broad sense, including not only the real Lie groups, but p-adic groups or groups over adele rings. His scientific work, being a synthesis of analysis, algebra and geometry, is still of lasting influence.

Harish-Chandra worked at the Institute of Advanced Study at Princeton from 1963. He was appointed IBM-von Neumann Professor in 1968.

He died of a heart attack at the end of a week long conference in Princeton, having earlier suffered from three heart attacks, the first being in 1969 and the third in 1982. In October 1983 a conference in honour of Armand Borel was held in Princeton [14]:-

... for the week of the conference, [Harish-Chandra's] vigour and force reasserted themselves. Princeton's warm, clear autumn weather prevailed and between lectures at the conference, on a lawn or a terrace of the Institute, he was the centre of a lively crowd, expressing his views on a variety of topics. On Sunday 16 October, the last day of the conference he and Lily had many of the participants to their home. He was a sparkling host. In the late afternoon, after the guests had departed, he went for his customary walk, and never returned alive.

Harish-Chandra received many awards in his career. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society (1973), a Fellow of the National Academy of Sciences (United States) (1981), the Indian Academy of Sciences and the Indian National Science Academy (1975). He won the Cole prize from the American Mathematical Society in 1954 for his papers on representations of semisimple Lie algebras and groups, and particularly for his paper On some applications of the universal enveloping algebra of a semisimple Lie algebra which he had published in the Transactions of the American Mathematical Society in 1951. In 1974, he received the Ramanujan Medal from Indian National Science Academy. He was awarded honorary degrees by Delhi University (1973) and Yale University (1981).

Having been both a physicist and a mathematician it is interesting to see Harish-Chandra's view of their relationship. This is described nicely in [14]:-

Although he was convinced that the mathematician's very mode of thought prevented him from comprehending the essence of theoretical physics, where, he felt, deep intuition and not logic prevailed, and sceptical of any mathematician who presumed to attempt to understand it, he was even more impatient with those mathematicians in whom a sympathy for theoretical physics was lacking, a failing he attributed in particular to the French school of the 1950s.

His character is described in [28]:-

... he was a tall, handsome man, who was somewhat reserved, but who possessed a formal courtesy that did not conceal the depth of his feelings and thought. In his early years he liked to paint and later expressed a fondness for the French Impressionists. ... One of his colleagues suggested that Harish-Chandra survives in his work, which faithfully mirrored his personality: intense, lofty, and uncompromising.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

دخلت غرفة فنسيت ماذا تريد من داخلها.. خبير يفسر الحالة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ثورة طبية.. ابتكار أصغر جهاز لتنظيم ضربات القلب في العالم

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تستعد لإطلاق الحفل المركزي لتخرج طلبة الجامعات العراقية

|

|

|