تاريخ الرياضيات

الاعداد و نظريتها

تاريخ التحليل

تار يخ الجبر

الهندسة و التبلوجي

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

العربية

اليونانية

البابلية

الصينية

المايا

المصرية

الهندية

الرياضيات المتقطعة

المنطق

اسس الرياضيات

فلسفة الرياضيات

مواضيع عامة في المنطق

الجبر

الجبر الخطي

الجبر المجرد

الجبر البولياني

مواضيع عامة في الجبر

الضبابية

نظرية المجموعات

نظرية الزمر

نظرية الحلقات والحقول

نظرية الاعداد

نظرية الفئات

حساب المتجهات

المتتاليات-المتسلسلات

المصفوفات و نظريتها

المثلثات

الهندسة

الهندسة المستوية

الهندسة غير المستوية

مواضيع عامة في الهندسة

التفاضل و التكامل

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

معادلات تفاضلية

معادلات تكاملية

مواضيع عامة في المعادلات

التحليل

التحليل العددي

التحليل العقدي

التحليل الدالي

مواضيع عامة في التحليل

التحليل الحقيقي

التبلوجيا

نظرية الالعاب

الاحتمالات و الاحصاء

نظرية التحكم

بحوث العمليات

نظرية الكم

الشفرات

الرياضيات التطبيقية

نظريات ومبرهنات

علماء الرياضيات

500AD

500-1499

1000to1499

1500to1599

1600to1649

1650to1699

1700to1749

1750to1779

1780to1799

1800to1819

1820to1829

1830to1839

1840to1849

1850to1859

1860to1864

1865to1869

1870to1874

1875to1879

1880to1884

1885to1889

1890to1894

1895to1899

1900to1904

1905to1909

1910to1914

1915to1919

1920to1924

1925to1929

1930to1939

1940to the present

علماء الرياضيات

الرياضيات في العلوم الاخرى

بحوث و اطاريح جامعية

هل تعلم

طرائق التدريس

الرياضيات العامة

نظرية البيان

Elementary Theory of integration -The Darboux Integral for Functions on RN

المؤلف:

Murray H. Protter

المصدر:

Basic Elements of Real Analysis

الجزء والصفحة:

81-89

1-12-2016

1151

Elementary Theory of integration -The Darboux Integral for Functions on RN

The reader is undoubtedly familiar with the idea of the integral and with methods of performing integrations. In this section we define the integral precisely and prove the basic theorems for the processes of integration.

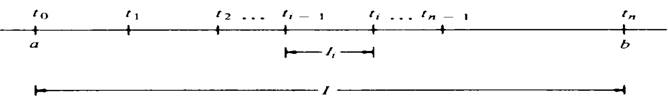

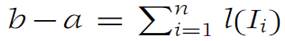

Let f be a bounded function whose domain is a closed interval I ={x : a ≤ x ≤ b}. We subdivide I by introducing points t1,t2,...,tn−1 that are interior to I. Setting a = t0 and b =tn and ordering the points so that t0 < t1 <t2 <...<tn, we denote by I1,I2,...,In the intervals Ii ={x : ti−1 ≤ x ≤ ti}. Two successive intervals have exactly one point in common. (See Figure 1.1.) We call such a decomposition of I into subintervals a subdivision of I, and we use the symbol Δ to indicate such a subdivision. Since f is bounded on I, it has a least upper bound (l.u.b.), denoted by M. The greatest lower bound (g.l.b.) of f on I is denoted by m. Similarly, Mi and mi denote the l.u.b. and g.l.b., respectively, of f on Ii . The length of the interval Ii is ti − ti−1; it is denoted by l(Ii).

Definitions

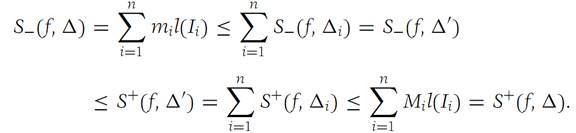

The upper Darboux sum of f with respect to the subdivision Δ , denoted S+(f,Δ), is defined by(1.1)

Similarly , the lower Darboux sum, denoted S−(f,Δ), is defined by(1.2)

Figure 1.1 A subdivision of I.

Suppose Δ is a subdivision a =t0 <t1 < ... < t n−1 <tn = b, with the corresponding intervals denoted by I1,I2,...,In. We obtain a new subdivision by introducing additional subdivision points between the various {ti}. This new subdivision will have subintervals I/1,I/2,...,I/m each of which is a part (or all) of one of the sub intervals of Δ. We denote this new subdivision by Δ/and call it a refinement of .

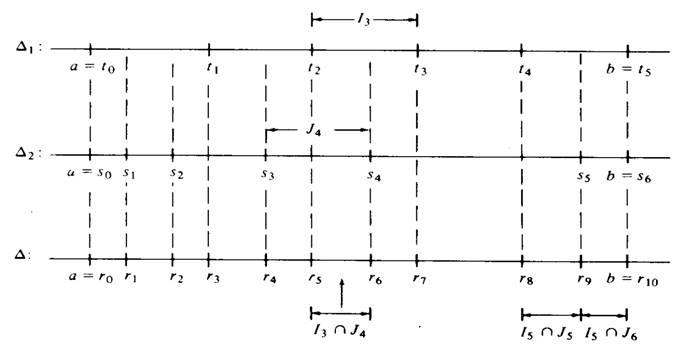

Suppose that Δ1 with subintervals I1,I2,...,In and that Δ2 with subintervals J1,J2,...,Jm are two subdivisions of an interval I. Wegetanew subdivision of I by taking all then dpoints of the subintervals of bothΔ1 and Δ2, arranging them in order of increasing size, and then labeling each subinterval having as its endpoints two successive subdivision points. Such a subdivision is called the common refinement ofΔ1 and Δ2, and each subinterval of this new subdivision is of the form Ii ∩ Jk, i = 1, 2,...,n, k = 1, 2,...,m. Each Ii ∩ Jk is either empty or entirely contained in a unique subinterval (Ii) of Δi and a unique subinterval (Jk) of Δ2. An illustration of such a common refinement is exhibited in Figure

1.2.

Theorem 1.1

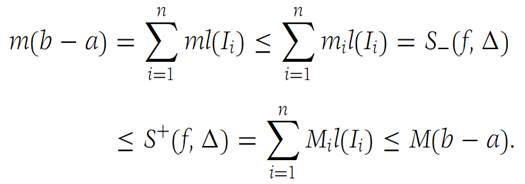

Suppose that f is a bounded function with domain I ={x:a ≤ x ≤ b}. Let Δ be a subdivision of I and suppose that M and m are the least upper bound and greatest lower bound of f on I, respectively. Then

(a)m(b − a) ≤ S−(f,Δ) ≤ S+(f,Δ) ≤ M(b − a).

(b) If Δ/is a refinement of Δ, then S−(f,Δ) ≤ S−(f,Δ/) ≤ S+(f,Δ/) ≤ S+(f, Δ).

(c) If Δ1 and Δ2 are any two subdivisions of I, thenS−(f,Δ1) ≤ S+(f,Δ2).

Figure 1.2 A common refinement.

Proof

(a) From the definition of least upper bound and greatest lower bound, we have

Also

Thus the inequalities in part (a) are an immediate consequence of the definition of S+ and S− as given in equations (1.1) and(1.2):

(b) To prove part (b), let Δi be the subdivision of Ii that consists of all those intervals of Δ/ that lie in Ii . Since each interval of Δ/ is in a unique Δi we have, applying part (a) to each Δi ,

(c) To prove part (c), let Δ be the common refinement of Δ1 and Δ2. Then, using the result in part (b), we obtain

Definitions

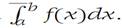

If f is a function on R1 that is defined and bounded on I ={x : a ≤ x ≤ b}, we define its upper and lower Darboux integrals by

we say that f is Darboux integrable, or just integrable, on , and we designate the common value by

The following results are all direct consequences of the above definitions.

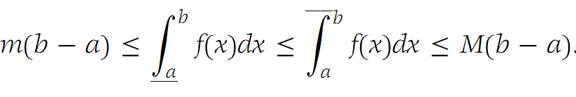

Theorem 1.2

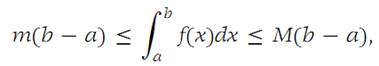

If m ≤ f(x) ≤ M for all x ∈ I ={x: a ≤ x ≤ b}, then

Proof

LetΔ1 andΔ2 be subdivisions of I. Then from parts (a) and (c) of Theorem 1.1, it follows that

We keep Δ1 fixed and let Δ2 vary over all possible subdivisions. Thus S+(f,Δ2) is alwayslarger than or equal to S−(f,Δ1), and so its greatest lower bound is alwayslarger than or equal to S−(f,Δ1). We conclude that

Now letting Δ1 vary over all possible subdivisions, we see that the least upper bound of S−(f,Δ1) cannot exceed The conclusion of the theorem follows.

The conclusion of the theorem follows.

The next theorem states simple facts about upper and lower Darboux integrals. The results all follow from the definitionsof inf, sup, and upper Darboux and lower Darboux integrals.

Theorem 1.3

Assuming that all functions below are bounded, we have the following formulas:(a) If g(x) = kf (x) for all x ∈ I ={x: a ≤ x ≤ b} and k is a positive number,

Then

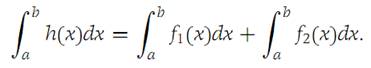

Corollary

If the functions considered in Theorem 1.3 are Darboux integrable, the following formulas hold:

- If g(x)= kf (x) and k is any constant, then

- If h(x) = f1(x) + f2(x), then

- If f1(x) ≤ f2(x) for all x ∈ I, then

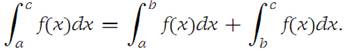

- Suppose f is Darboux integrable on I1 ={x: a ≤ x ≤ b} and on I2 ={x: b ≤ x ≤ c}. Then it is Darboux integrable on I ={x: a ≤ x ≤ c}, and(1.3)

It is useful to define

Then formula (1.3) above is valid whether or not b is between a and c so long as all the integrals exist. It is important to be able to decide when a particular function is inte grable. The next theorem gives a necessary and sufficient condition for integrability.

Theorem 1.4

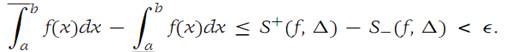

Suppose that f is bounded on an interval I ={x: a ≤ x ≤ b}. Then f is integrable ⇔ for every Ԑ> 0 there is a subdivision Δ of I such that

S+(f,Δ) − S−(f,Δ) <Ԑ.

Suppose that condition (1.4) holds. Then from the definitions of upper and lower Darboux integrals, we have

Since this inequality holds for every Ԑ> 0 and the left side of the inequality is independent of Ԑ, it follows that

Hence f is integrable.

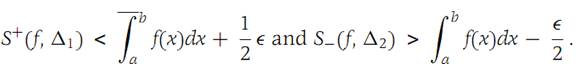

Now assume that f is integrable; we wish to establish inequality (1.4).

For any Ԑ> 0 there are subdivisions Δ1 and Δ2 such that(1.5)

We choose Δ as the common refinement of Δ1 and Δ2. Then (from Theorem 1.1)

Substituting inequalities (1.5) into the above expression and using the fact that

As required.

If f is continuous on the closed interval I ={x: a ≤ x ≤ b}, then f is integrable.

The function f is uniformly continuous, and hence for any Ԑ> 0 there Is a δ such that

Choose a subdivision Δ of I such that no subinterval of Δ has length larger than δ. This allowsus to establish formula (1.4), and the result follows from Theorem 1.4.

Theorem 1.5(Mean-value theorem for integrals).

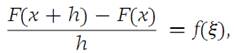

Suppose that f is continuous on I ={x: a ≤ x ≤ b}. Then there is a number ξ in I such that

According to Theorem 1.2, we have(1.6)

where m and M are the minimum and maximum of f on I, respectively. From the Extreme-value theorem there are numbers x0 and x1 ∈ I such that f(x0)= m and f(x1) =M. From inequalities (1.6) it follows that

where A is a number such that f(x0) ≤ A ≤ f(x1). Then the intermediate value theorem show that there is a number ξ ∈ I such that f(ξ)= A.

We now present two forms of the Fundamental theorem of calculus, a result that shows that differentiation and integration are inverse processes.

Theorem 1.6(Fundamental theorem of calculus—first form).

Suppose that f is continuous on I ={x:a ≤ x ≤ b}, and that F is defined by

Then F is continuous on I, and F/(x) =f(x) for each x ∈ I1 ={x: a<x<b}.

Since f is integrable on every subinterval of I, we have

We apply the Mean-value theorem for integrals(Theorem 1.5) to the last term on the right, getting

where ξ is some number between x and x + h. Now, let 8> 0 be given.

There is a δ> 0 such that |f(y) − f(x)| <Ԑ for all y on I1 (taking ξ y) with |y − x| <δ. Thus, if 0 < |h| <δ, we find that

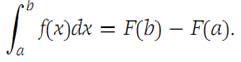

Theorem 1.7(Fundamental theorem of calculus—second form).

Suppose that f and F are continuous on I ={x:a ≤ x ≤ b} and that F/(x) = f(x) for each

x ∈ I1 ={x:a<x<b}. Then(1.7)

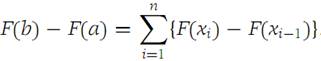

We consider a subdivision Δ of I. We write

We apply the Mean-Value theorem to each term in the sum. Then as the

mesh size tends to zero we get (1.7).

1. Compute S+(f,Δ) and S−(f,Δ) for the function f : x → x2 defined on I ={x :0 ≤ x ≤ 1} where Δ is the subdivision of I into 5subintervals of equal size.

2. (a) Given the function f : x → x3 defined on I ={x :0 ≤ x ≤ 1},suppose Δ is a subdivision and Δ/is a refinement of Δ that adds one more point. Show that S+(f,Δ/)<S+(f,Δ) and S−(f,Δ/)>S−(f, Δ).

(b) Give an example of a function f defined on I such that S+(f,Δ/ ) = S+(f,Δ) and S−(f,Δ/) =S−(f,Δ)

Basic Elements of Real Analysis, Murray H. Protter, Springer, 1998 .Page(81-89)

الاكثر قراءة في التحليل الحقيقي

الاكثر قراءة في التحليل الحقيقي

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)