علم الكيمياء

تاريخ الكيمياء والعلماء المشاهير

التحاضير والتجارب الكيميائية

المخاطر والوقاية في الكيمياء

اخرى

مقالات متنوعة في علم الكيمياء

كيمياء عامة

الكيمياء التحليلية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء التحليلية

التحليل النوعي والكمي

التحليل الآلي (الطيفي)

طرق الفصل والتنقية

الكيمياء الحياتية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الحياتية

الكاربوهيدرات

الاحماض الامينية والبروتينات

الانزيمات

الدهون

الاحماض النووية

الفيتامينات والمرافقات الانزيمية

الهرمونات

الكيمياء العضوية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الهايدروكاربونات

المركبات الوسطية وميكانيكيات التفاعلات العضوية

التشخيص العضوي

تجارب وتفاعلات في الكيمياء العضوية

الكيمياء الفيزيائية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الفيزيائية

الكيمياء الحرارية

حركية التفاعلات الكيميائية

الكيمياء الكهربائية

الكيمياء اللاعضوية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء اللاعضوية

الجدول الدوري وخواص العناصر

نظريات التآصر الكيميائي

كيمياء العناصر الانتقالية ومركباتها المعقدة

مواضيع اخرى في الكيمياء

كيمياء النانو

الكيمياء السريرية

الكيمياء الطبية والدوائية

كيمياء الاغذية والنواتج الطبيعية

الكيمياء الجنائية

الكيمياء الصناعية

البترو كيمياويات

الكيمياء الخضراء

كيمياء البيئة

كيمياء البوليمرات

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الصناعية

الكيمياء الاشعاعية والنووية

Molecular Anatomy Reveals Evolutionary Relationships

المؤلف:

David L. Nelson, Michael M. Cox

المصدر:

Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry 6th ed 2012

الجزء والصفحة:

6th ed -p36

7-8-2016

2371

Molecular Anatomy Reveals Evolutionary Relationships

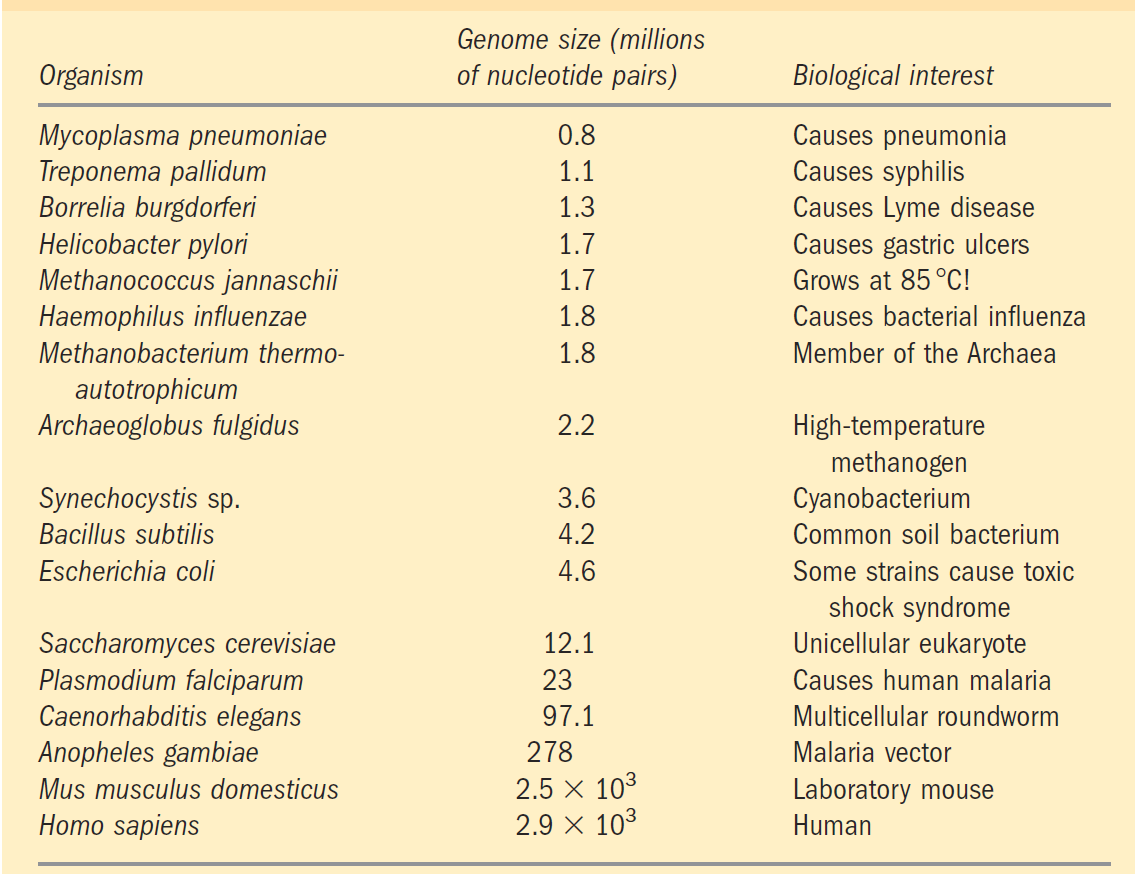

The eighteenth-century naturalist Carolus Linnaeus recognized the anatomic similarities and differences among living organisms and used them to provide a framework for assessing the relatedness of species. Charles Darwin, in the nineteenth century, gave us a unifying hypothesis to explain the phylogeny of modern organisms—the origin of different species from a common ancestor. Biochemical research in the twentieth century revealed the molecular anatomy of cells of different species—the monomeric subunit sequences and the three-dimensional structures of individual nucleic acids and proteins. Biochemists now have an enormously rich and increasing treasury of evidence that can be used to analyze evolutionary relationships and to refine evolutionary theory. The sequence of the genome (the complete genetic endowment of an organism) has been entirely determined for numerous eubacteria and for several archaebacteria; for the eukaryotic microorganisms Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Plasmodium sp.; for the plants Arabidopsis thaliana and rice; and for the multicellular animals Caenorhabditis elegans (a roundworm), Drosophila melanogaster (the fruit fly), mice, rats, and Homo sapiens (you) (Table 1–1). More sequences are being added to this list regularly. With such sequences in hand, detailed and quantitative comparisons among species can provide deep insight into the evolutionary process. Thus far, the molecular phylogeny derived from gene sequences is consistent with, but in many cases more precise than, the classical phylogeny based on macroscopic structures. Although organisms have continuously diverged at the level of gross anatomy, at the molecular level the basic unity of life is readily apparent; molecular structures and mechanisms are remarkably similar from the simplest to the most complex organisms. These similarities are most easily seen at the level of sequences, either the DNA sequences that encode proteins or the protein sequences themselves. When two genes share readily detectable sequence similarities (nucleotide sequence in DNA or amino acid sequence in the proteins they encode), their sequences

Carolus Linnaeus, Charles Darwin,

1701–1778 1809–1882

TABLE 1–1 Some Organisms Whose Genomes Have Been Completely Sequenced

are said to be homologous and the proteins they encode are homologs. If two homologous genes occur in the same species, they are said to be paralogous and their protein products are paralogs. Paralogous genes are presumed to have been derived by gene duplication followed by gradual changes in the sequences of both copies (Fig. 1–1). Typically, paralogous proteins are similar not only in sequence but also in three-dimensional structure, although they commonly have acquired different functions during their evolution. Two homologous genes (or proteins) found in different species are said to be orthologous, and their protein products are orthologs. Orthologs are commonly found to have the same function in both organisms, and when a newly sequenced gene in one species is found to be strongly orthologous with a gene in another, this gene is presumed to encode a protein with the same function in both species. By this means, the function of gene products can be deduced from the genomic sequence, without any biochemical characterization of the gene product. An annotated genome includes, in addition to the DNA sequence itself, a description of the likely function of each gene product, deduced from comparisons with other genomic sequences and established protein functions. In principle, by identifying the pathways (sets of enzymes) encoded in a genome, we can deduce from the genomic sequence alone the organism’s metabolic capabilities. The sequence differences between homologous genes may be taken as a rough measure of the degree to which the two species have diverged during evolution— of how long ago their common evolutionary precursor gave rise to two lines with different evolutionary fates. The larger the number of sequence differences, the earlier the divergence in evolutionary history. One can construct a phylogeny (family tree) in which the evolutionary distance between any two species is represented by their proximity on the tree.

As evolution advances, new structures, processes, or regulatory mechanisms are acquired, reflections of the changing genomes of the evolving organisms. The genome of a simple eukaryote such as yeast should have genes related to formation of the nuclear membrane, genes not present in prokaryotes. The genome of an insect should contain genes that encode proteins involved in specifying the characteristic insect segmented body plan, genes not present in yeast. The genomes of all vertebrate animals should share genes that specify the development of a spinal column, and those of mammals should have unique genes necessary for the development of the placenta, a characteristic of mammals—and so on. Comparisons of the whole genomes of species in each phylum may lead to the identification of genes critical to fundamental evolutionary changes in body plan and development.

FIGURE 1–1 Generation of genetic diversity by mutation and gene duplication. 1 A mistake during replication of the genome of species A results in duplication of a gene (gene 1). The second copy is superfluous; mutations in either copy will not be deleterious as long as one good version of gene 1 is maintained. 2 As random mutations occur in one copy, the gene product changes, and in rare cases the product of the “new” gene (now gene 2) acquires a new function. Genes 1 and 2 are paralogs. 3 If species A undergoes many mutations in many genes over the course of many generations, its genome may diverge so greatly from that of the original species that it becomes a new species (species B)—that is, species A and species B cannot interbreed. Gene 1 of species A is likely to have undergone some mutations during this evolutionary period (becoming gene 1*), but it may retain enough of the original gene 1 sequence to be recognized as homologous with it, and its product may have the same function as (or similar function to) the product of gene 1. Gene 1* is an ortholog of gene 1.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الحياتية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الحياتية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)