تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

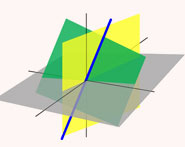

الهندسة

الهندسة

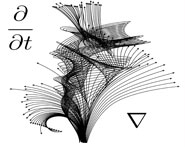

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 13-7-2016

Date: 17-7-2016

Date: 14-7-2016

|

Born: July 1793 in Sneinton, Nottingham, England

Died: 31 May 1841 in Sneinton, Nottingham, England

George Green's father, also called George Green, was a baker in Nottingham. After serving his apprenticeship to a baker in Nottingham George Green Senior had married Sarah Butler (the mathematician's mother) in 1791 and Sarah's father had helped George Green Senior to buy his own bakery in Wheatsheaf Yard in Nottingham. George and Sarah had one son and one daughter. The son was George Green, the mathematician and, although the date of his birth is unknown, he was baptised on 14 July 1793. His sister Ann was born two years later and the family were reasonably prosperous with the bakery business being successful.

In September 1800 there were riots in England when food prices were high and people did not have enough to eat. The corn dealers and bakers were blamed for keeping back food until the prices rose even higher and crowds of people broke into bakers and tried to steal food. George Green's bakery was attacked and the he wrote a letter to the mayor asking for protection (the spelling and capital letters follow Green's letter):-

Sept 1th 1800 To the Right Worshipfull the Mayor and his Bretheren haveing all my Windows Broke Last night and being much thretend tonight with more mischief being done to me such as entering my House therefore Gentlemen I most Humbly crave your protection such as the Berer of this can explain to you from your Humble servant George Green.

Young George Green went to Robert Goodacre's school in 1801, the year after the riots. He was only eight years old when he began his schooling and only nine when he left the school in midsummer 1802. His only schooling, therefore, consisted of four terms but, despite the short time he spent there, since Robert Goodacre's was the best and most expensive school in Nottingham, George was taught much in the four terms. George's sister Ann went on to marry William Tomlin and he was to write on George Green's life after George died. Of his time at Robert Goodacre's school, Tomlin writes:-

... he pursued with undeviating constancy the same as in his mature years an intense application to mathematics. ... his profound knowledge in mathematics soon exceeded that of Robert Goodacre.

It is hard to see quite why Green became interested in mathematics at this age or, for that matter, whether he had access to mathematical works of any type. However, in 1802, Green left school as a nine year old boy to work in his father's bakery business. He probably learnt a little of Latin, Greek and French at school but it is hard to see how even a bright eight year old boy in a good school could learn more than the briefest of introductions to these subjects.

George Green Senior ran a successful bakery business and he was able to buy several houses in Nottingham. In 1807 he bought a plot of land at Sneinton, just outside Nottingham. The sale was made by auction at 26 February 1807 and in the advertisement for the sale the plot is described as:-

A freehold estate, tythe-free, and the Land Tax redeemed, situate at Snenton, near Nottingham; consisting of excellent pasture land, and affording for Building upon one of the first Situations in the Kingdom, commanding most extensive Views of the River Trent, Trent Vale, Clifton Woods, Colwick, Belvoir Castle, and a rich and highly cultivated Country, diversified by numberless other picturesque objects...

Having bought the land, he built on it a brick wind corn-mill, clearly a useful thing for a baker to own. The mill stood 16 metres high and was one of the first two brick mills in the county of Nottinghamshire. Green's father employed a manager to run the mill, and Green himself worked there. In 1817 Green Senior built a family house beside the mill and Green together with his mother and father went to live there. [The mill has been restored and we strongly recommend anyone who is visiting Nottingam to pay a visit.] Green's sister Ann did not move to Sneinton as she had married William Tomlin in 1816 and they were living in a fashionable part of Nottingham.

Green must have continued working on mathematics through the years that he worked at his father's mill. However, we have no knowledge whatsoever of how he could have become acquainted with the most advanced mathematics of his day, which indeed is what happened. In [3] Cannell discusses whether there were any mathematicians living in Nottingham who could have given Green access to advanced French mathematical ideas. She comes up with only one possible candidate, John Toplis who was a mathematics graduate of Queens' College Cambridge.

Toplis had become unhappy with the mathematics being taught at Cambridge and had tried to influence others to learn more of the mathematics being developed in France. He translated the first volume of Laplace's Mécanique céleste into English and he published this in Nottingham in 1814. At this time he was the headmaster of the Free Grammar School in Nottingham, and he remained there until 1819 when he returned to Cambridge as Dean of Queens' College. Certainly Green could have known Toplis since, before he moved to the new family home at the mill in 1817, Green was living in Goosegate in Nottingham just one street away from the Free Grammar School where Toplis lived at that time. As Cannell writes [3]:-

There is no proof that John Toplis was George Green's mentor but circumstantial evidence suggests strongly that he was guiding him in the new mathematics and helping him with the French he undoubtedly acquired in order to read the works of other French mathematicians, such as Lacroix, Poisson and Biot.

The manager of Green's mill was William Smith and he had a daughter Jane Smith. George Green never married Jane Smith but together they had seven children. His relationship with her must have started in 1823 or earlier as their first child was born in 1824. Certainly in 1823 Green joined the Nottingham Subscription Library which was situated in Bromley House. This was an important event in Green's scientific development as it gave him access to a few scientific works, but perhaps most importantly of all, it gave him access to the Transactions of the Royal Society of London. In this publication Green could read some of the latest mathematical work and it also reported on works published in other countries.

Green studied mathematics on the top floor of the mill, entirely on his own. The years between 1823 and 1828 were not easy for Green, and certainly not the most conducive to study. As well as having a full time job in the mill, two daughters were born, the one in 1824 mentioned above, and a second in 1827. Between these two events his mother had died in 1825 and his father was to die in 1829. Yet despite the difficult circumstances and despite his flimsy mathematical background, Green published one of the most important mathematical works of all time in 1828.

On 14 December 1827 he published an advertisement in the Nottingham review:-

In the Press, and shortly will be published, by subscription, An Essay on the Application of Mathematical Analysis to the Theories of Electricity and Magnetism. By George Green. Dedicated (by permission), to his Grace the Duke of Newcastle, K.G. Price to Subscribers, 7s. 6d. The Names of Subscribers will be received at the Booksellers, and at the Library, Bromley House.

The Essay was published in March 1828 and there were 51 subscribers, most of whom were members of the Nottingham Subscription Library and paid 7s. 6d. for a work of which they could hardly have understood a word. In [1] details are given of Green's preface:-

In the preface Green indicated that his "limited sources of information" prevented his giving a proper historical sketch of the mathematical theory of electricity, and indeed, he cites few sources. Among them are Cavendish's single-fluid theoretical study of electricity of 1771, two memoirs by Poisson of1812 on surface electricity and three on magnetism (1821-1823), and contributions by Arago, Laplace, Fourier, Cauchy, and T Young. The preface concludes with a request that the work be read with indulgence, in view of the limitations of the author's education.

Also in [1] some details are given of the contents this important publication:-

The Essay begins with introductory observations emphasising the central role of the potential function. Green coined the term 'potential' to denote the results obtained by adding the masses of all the particles of a system, each divided by its distance from a given point. The general properties of the potential function are subsequently developed and applied to electricity and magnetism. The formula connecting surface and volume integrals, now known as Green's theorem, was introduced in the work, as was "Green's function" the concept now extensively used in the solution of partial differential equations.

The Essay may have been of great importance but this was not realised by anyone at the time of its publication. Nobody with sufficient mathematical skills to appreciate its importance had seen the work. Green carried on working his mill and, in 1829 on the death of his father, he became solely responsible for the family business. His third child, and first son, was born in 1829. Things changed however, when he made contact with Sir Edward Bromhead.

Sir Edward Bromhead was one of the subscribers to the Essay and he had written immediately to Green offering to send any further papers to the Royal Society of London, the Royal Society of Edinburgh or the Cambridge Philosophical Society. Bromhead had studied mathematics at Cambridge and had been a member of the Analytic Society. In fact what may have been the last meeting of that Society had been held at Thurlby Hall on 20 December 1817 with Bromhead in the chair. Although Bromhead was not able to appreciate the high importance of Green's essay, he did realise that Green was a very good mathematician. Green took Bromhead's offer as mere politeness and did not respond until January 1830 when a friend persuaded him to follow up Bromhead's letter.

For three years Green and Bromhead met at Thurlby Hall and during this time Green wrote three further papers. Two on electricity were sent by Bromhead to the Cambridge Philosophical Society where they were published, one in 1833 and the other in 1834. The third was on hydrodynamics and this work was published by the Royal Society of Edinburgh (of which Bromhead was a Fellow) in 1836. Bromhead was a good person for Green to become friendly with since he had good contacts with mathematicians at Cambridge. Bromhead's close friends there included Charles Babbage, John Herschel and George Peacock and he suggested to Green in April 1833 that he should consider studying mathematics at Cambridge. In June 1833 Bromhead went to Cambridge for a reunion and asked Green to go with him. However Green certainly did not realise the importance of his work. He wrote to Bromhead:-

You were kind enough to mention a journey to Cambridge on June 24th to see your friends Herschel, Babbage and others who constitute the Chivalry of British Science. Being as yet only a beginner I think I have no right to go there and must defer the pleasure until I shall have become tolerably respectable as a man of science should that day ever arrive.

However Green took Bromhead's advice, left his mill and became an undergraduate at Cambridge in October 1833 at the age of 40. He was admitted to Caius College where Bromhead had studied. He wrote to Bromhead in May 1834:-

I am very happy here and am I fear too much pleased with Cambridge. This takes me in some measure from those pursuits which ought to be my proper business, but I hope on my return to lay aside my freshnesses and become a regular Second Year Man.

The mathematics examinations did not prove hard for Green, but the other topics such as Latin and Greek proved much harder for someone with only four terms of school education. He graduated as fourth Wrangler in 1837, the second Wrangler that year being Sylvester. The following quote appears in [16]:-

Green and Sylvester were the first men of the year, but Green's want of familiarity with ordinary boy's mathematics prevented him from coming to the top in a time race.

After graduating he remained at Cambridge and worked on his own mathematics. In 1838 and 1839 he had two papers on hydrodynamics (in particular wave motion in canals), two papers on reflection and refraction of light and two papers on reflection and refraction of sound published by Cambridge Philosophical Society.

Bishop Harvey Goodwin was an undergraduate at Cambridge during these years following Green's graduation. He wrote of Green [3]:-

He stood head and shoulders above all his contemporaries inside and outside the University.

Goodwin is also quoted in [16]:-

I was twice examined by Green. He set the problem paper in two out of the three of my college examinations... He never assisted as far as I know in lectures. This might be owing to his habits of life. His manner in the examination room was gentle and pleasant.

Green was elected to a Perse fellowship on 31 October 1839. This of course was possible since he did satisfy the condition of not being married, and having six children, which he had at this time, was not relevant. His time at Cambridge after being elected to the fellowship was very short indeed. By May 1840 he had returned to Nottingham suffering from ill health. A few weeks later his seventh child was born. Green clearly felt that his illness was very serious and in July 1840 he wrote a will in which he states that his health was poor but no details of the illness are given. However it would appear that he still hoped to return to Cambridge since he describes himself as:-

... late of Sneinton in the County of Nottingham and now of Caius College Cambridge, Fellow of such College.

His will left all his property in Nottingham to Jane while the property at Sneinton was left to his seven children.

We do know that Green died in the house where Jane Smith and his seven children lived. Jane reported his death and was with Green when he died. Rather remarkably, this is the only record of Green living in the same house as Jane Smith and his children.

The Nottingham Review published a short obituary on 11 June which showed they knew little of his life and less of the importance of his work:-

... we believe he was the son of a miller, residing near Nottingham, but having a taste for study, he applied his gifted mind to the science of mathematics, in which he made a rapid progress. In Sir Edward Ffrench Bromhead, Bart., he found a warm friend, and to his influence he owed much, while studying at Cambridge. Had his life been prolonged, he might have stood eminently high as a mathematician.

Of course, Green never knew the importance of his mathematics. That was only realised after his death [1]:-

Only a few weeks before Green's death, William Thomson had been admitted to St Peter's College, Cambridge. In a paper by Robert Murphy published in the Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, Thomson noticed a reference to Green's Essay, although Murphy did not mention any of his other works published in that journal. Thomson was unable to find a copy of the Essay until, just after receiving his degree in January 1845, his coach, William Hopkins, gave him three copies. Sixty years later Thomson recalled his excitement and that of Liouville and Sturm, to whom he showed the work in Paris in the summer of 1845. After returning to Cambridge, Thomson was responsible for republishing the work, with an introduction (1850-54). Through Thomson, Maxwell, and others, the general mathematical theory of potential developed by an obscure, self-taught miller's son would lead to the mathematical theories of electricity underlying twentieth-century industry.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|