تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

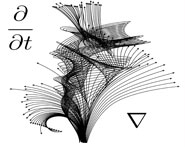

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 4-1-2016

Date: 30-12-2015

Date: 30-12-2015

|

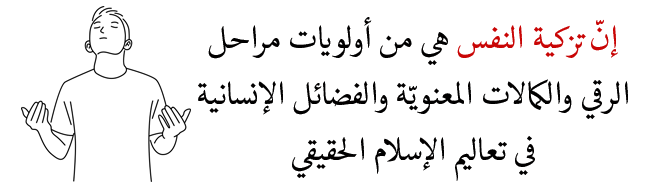

The abacus is the most ancient calculating device known. It has endured over time and is still in use in some countries. An abacus consists of a wooden frame, rods, and beads. Each rod represents a different place value—ones, tens, hundreds, thousands, and so on. Each bead represents a number, usually 1 or 5, and can be moved along the rods. Addition and subtraction can easily be performed by moving beads along the wires of the abacus.

The word abacus is Latin. It is taken from the Greek word abax, which means “flat surface.” The predecessors to the abacus—counting boards—

were just that: flat surfaces. Often they were simply boards or tables on which pebbles or stones could be moved to show addition or subtraction.

The earliest counting tables or boards may simply have been lines drawn in the sand. These evolved into actual tables with grooves in them to move the counters.

Since counting boards were often made from materials that deteriorated over time, few of them have been found. The oldest counting board that has been found is called the Salamis Tablet. It was found on the island of Salamis, a Greek island, in 1899. It was used by the Babylonians around 300 B.C.E. Drawings of people using counting boards have been found dating back to the same time period.

There is evidence that people were using abacuses in ancient Rome (753B.C.E.–476 C.E.). A few hand abacuses from this time have been found. They are very small, fitting in the palm of your hand. They have slots with beads in them that can be moved back and forth in the slots similar to counters on a counting board. Since such a small number of these have been found, they probably were not widely used. However, they resemble the Chinese and Japanese abacuses, suggesting that the use of the abacus spread from Greece and Rome to China, and then to Japan and Russia.

The Suanpan

In China, the abacus is called a “suanpan.” Little is known about its early use, but rules on how to use it appeared in the thirteenth century. The suanpan consists of two decks, an upper and a lower, separated by a divider. The upper deck has two beads in each column, and the lower deck has five beads in each column. Each of the two beads in the ones column in the top deck is worth 5, and each bead in the lower deck is worth 1. The column farthest to the right is the ones column. The next column to the left is the tens column, and so on. The abacus can then be read across just as if you were reading a number. Each column can be thought of in terms of place value and the total of the beads in each column as the digit for that place value.

The beads are moved toward the middle beam to show different numbers. For example, if three beads from the lower deck in the ones column have been moved toward the middle, the abacus shows the number 3. If one bead from the upper deck and three beads from the lower deck in the ones column have been moved to the middle, this equals 8, since the bead from the upper deck is worth 5.

To add numbers on the abacus, beads are moved toward the middle.

To subtract numbers, beads are moved back to the edges of the frame. Look at the following simple calculation (12 + 7 =19) using a suanpan.

The abacus on the left shows the number 12. There is one bead in the lower deck in the tens place, so the digit in the tens column is 1. There are two beads in the lower deck in the ones place, so the digit in the ones column is 2. This number is then read as 12. To add 7 to the abacus, simply move one bead in the ones column of the top deck (5) and two more beads in the ones column of the lower deck (2). Now the suanpan shows 9 in the ones column and 10 in the tens column equaling 19.

The Soroban

The Japanese abacus is called the soroban. Although not used widely until the seventeenth century, the soroban is still used today. Japanese students first learn the abacus in their teens, and sometimes attend special abacus schools. Contests have even taken place between users of the soroban and the modern calculator. Most often, the soroban wins. A skilled person is usually able to calculate faster with a soroban than someone with a calculator.

The soroban differs only slightly from the Chinese abacus. Instead of two rows of beads in the upper deck, there is only one row. In the lower deck, instead of five rows of beads, there are only four. The beads equal the same amount as in the Chinese abacus, but with one less bead, there is no carrying of numbers. For example, on the suanpan, the number 10 can be shown by moving the two beads in the upper deck of the ones column or only one bead in the upper deck of the tens column. On the soroban, 10 can only be shown in the tens column. The beads in the ones column only add up to 9 (one bead worth 5 and four beads each worth 1).

The Schoty

The Russian abacus is called a schoty. It came into use in the 1600s. Little is known about how it came to be. The schoty is different from other abacuses in that it is not divided into decks. Also, the beads on a schoty move on horizontal rather than vertical wires. Each wire has ten beads and each bead is worth 1 in the ones column, 10 in the tens column, and so on. The schoty also has a wire for quarters of a ruble, the Russian currency. The two middle beads in each row are dark colored. The schoty shows 0 when all of the beads are moved to the right. Beads are moved from left to right to show numbers. The schoty is still used in modern Russia. ______________________________________________________________________________________________

Reference

Pullan, J.M. The History of the Abacus. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc., 1969.

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اتحاد كليات الطب الملكية البريطانية يشيد بالمستوى العلمي لطلبة جامعة العميد وبيئتها التعليمية

|

|

|