Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods|

Read More

Date: 2025-04-07

Date: 2024-01-23

Date: 7-3-2022

|

The argument of evaluative adverbs

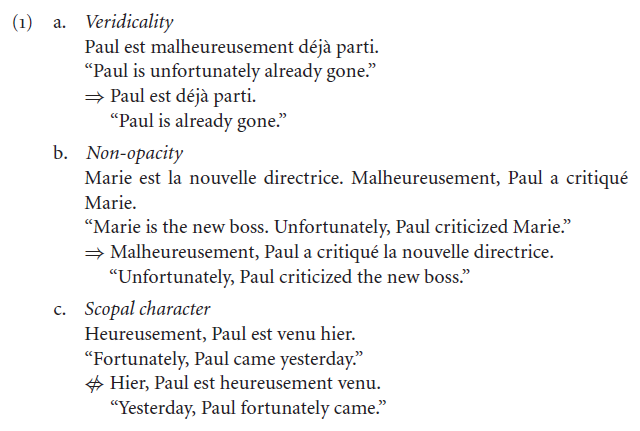

Evaluative adverbs have a series of three properties which make them distinct from other, better studied adverb classes.1 First, evaluatives are veridical: a simple declarative sentence containing an evaluative systematically entails the corresponding sentence without the evaluative. Second, evaluatives are nonopaque: coreferring expressions can be substituted in their scope. Third, evaluatives are scopal: they participate in scope ambiguities correlated with their syntactic position.

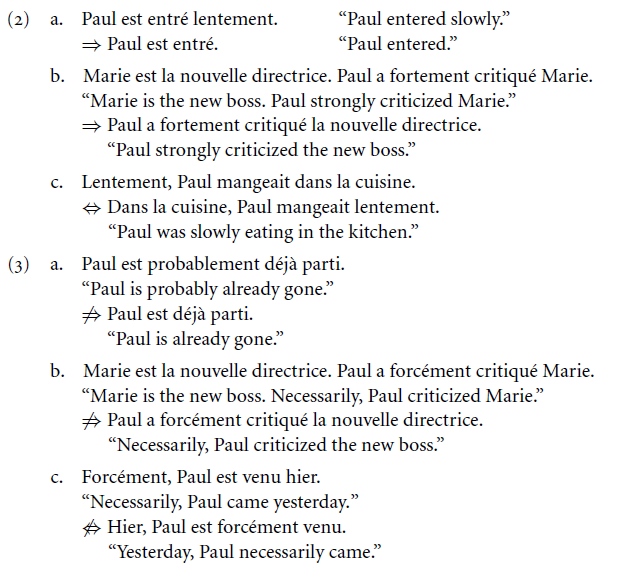

This set of properties distinguishes evaluatives from both manner adverbs such as lentement ‘slowly,’ fortement ‘strongly,’ etc., and modal adverbs such as probablement ‘probably,’ forcément ‘necessarily,’ etc.: manner adverbs are veridical and do not give rise to opacity, but they are scopeless (2). A wellestablished tradition stemming from Davidson (1967) accounts for the properties of manner adverbs by taking them to be predicates of events. On the other hand, modal adverbs are scopal, but they are not veridical and do give rise to opacity (3). A well-established tradition stemming from Montague (1970) accounts for this set of properties by taking modal adverbs to be intensional predicates – or, more precisely, predicates of propositions. What is interesting is that the Davidsonian analysis of manner adverbs and the Montagovian analysis of modal adverbs rely on a single insight to account for the three constrasts between the two classes of adverbs. From this perspective it is quite surprising that a class of adverbs should exhibit a mix of properties that puts them halfway between modal and manner adverbs.

Previous accounts have tried to assimilate evaluatives to either predicates of events or predicates of propositions. Bellert (1977: 342) postulates that while modals take a proposition argument, evaluatives take “the fact, event, or state of affairs denoted by the sentence in which they occur.” A similar move is proposed in Wyner (1994), where evaluatives are treated as a special case of predicates of events.2

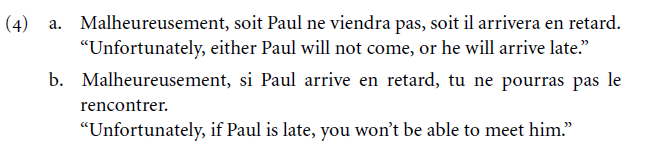

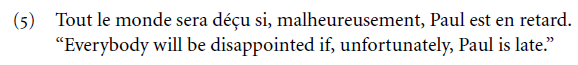

Events or states of affairs, in contrast with propositions, are parts of the world. Clearly, Bellert’s analysis is not adequate, as shown by two observations. First, as noted by Bartsch (1976: 40–43), the analysis of evaluatives as predicates of events or states of affairs does not correspond to the intuitive semantics of a sentence with an evaluative. Sentence (4) does not describe an unfortunate state of affairs, but says that it is unfortunate for this state of affairs to hold. Second, evaluatives can take scope over a disjunction or a conditional (Geuder 2000: 149–152).

It is difficult to think of states of affairs or events as being disjunctive or conditional. Rather such properties characterize abstract objects, in contrast with parts of the world (Asher 1993: 40–57).

Turning now to abstract objects, the argument of evaluatives could be either a fact or a proposition. It is tempting to say that it is a fact, given the similarity between veridicality and the factive presupposition associated with the argument of so-called factive predicates such as the verb regretter‘regret.’ However, there is a great deal of unclarity as to the status of facts in the ontology. First, some authors reduce facts to true propositions. But the argument of an evaluative cannot be a fact in that sense, since evaluative adverbs occur inside the antecedent of a conditional; in that case the argument of the evaluative does not have to be true/factual.

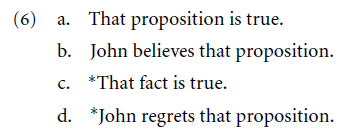

A different tradition takes facts to be an ontological category distinct from that of true propositions (Asher 1993; Peterson 1997; Ginzburg and Sag 2001). The motivation for this ontological distinction is distributional: some predicates, such as the adjective true, the noun proposition, or the verb believe take a proposition as their argument, while others, such as the noun fact or the verb regret, take a fact as their argument. This is taken to account for example for the contrasts in (6).

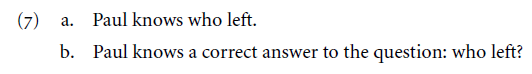

Moreover, the distinction can be taken to account for the behavior of resolutive predicates, that can embed an interrogative but give rise to the “resolutive” reading corresponding to the paraphrase in (7). Under Ginzburg and Sag’s (2001) account, know takes a fact as its argument, and interrogative meaning can be type-coerced to fact meaning.

While other aspects of Ginzburg and Sag (2001) are convincing, the defense of facts strikes us as ill-supported. First, as Godard and Jayez (1999) and Jayez and Godard (1999) show, the denotation of the noun fact does not correspond to the ontological notion of fact, and may vary slightly from language to language. A striking example of this is the fact that the French word fait ‘fact’ cannot serve as a complement to the verb savoir ‘know.’

What this and other data show is that one should be wary of any argument resting on the lexical semantics of individual abstract nouns (such as proposition, fact, situation, possibility) since the use of these nouns in ordinary usage does not fit their use in ontological discussions.

Even when restricting the discussion to the analysis of verbs, it turns out that the notion of fact does not play any crucial role in Ginzburg and Sag’s analysis. To account for the difference between resolutive predicates (such as know) and emotive predicates such as regret (which do not embed interrogatives; see Peterson 1997), Ginzburg and Sag (2001: 353) silently abandon the type coercion analysis in favor of a polysemy analysis: resolutive predicates have two lexical entries, one for their declarative-embedding use, and one for their interrogative-embedding use. But once these predicates have two lexical entries, there is no real sense in which resolutive predicates always take the same type of argument; thus the notion of a fact does not play any role in accounting for the distributional data.

To sum up, the general unclarity of the notion of fact suggests that taking evaluatives to be predicates of facts will raise more questions than it solves. Thus we follow Geuder (2000) in assuming that evaluatives are predicates of propositions. In this respect, they do not differ from modals, which also take a proposition argument. Of course, such a move means that we cannot rely on the semantic type of evaluatives to account for their veridicality (1a) or their non-opacity (1b).

1 Although he does not address the issue in the same terms as ours, and focuses on an adverb (appropriately) with no equivalent in French, Wyner (1994: chapter 2) must be credited for clearly stating how adverbs in this class pose a specific problem for standard theories of the semantics of adverbs.

2 Unlike Bellert’s,Wyner’s analysis is explicitly cast in a neo-Davidsonian approach to modification (see e.g. Parsons 1990). In Wyner’s account, evaluatives are basically predicates of events, which accounts for their veridicality and lack of opacity. They differ from scopeless modifiers such as manner, locative, and temporal adverbials in introducing a minimization operation on the described eventuality: an evaluative predicates over the minimal event verifying the description provided by the rest of the sentence.

|

|

|

|

حقن الذهب في العين.. تقنية جديدة للحفاظ على البصر ؟!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"عراب الذكاء الاصطناعي" يثير القلق برؤيته حول سيطرة التكنولوجيا على البشرية ؟

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جمعية العميد تعقد اجتماعها الأسبوعي لمناقشة مشاريعها البحثية والعلمية المستقبلية

|

|

|