Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods|

Read More

Date: 2024-01-11

Date: 2024-01-09

Date: 2024-01-19

|

Degree modifiers

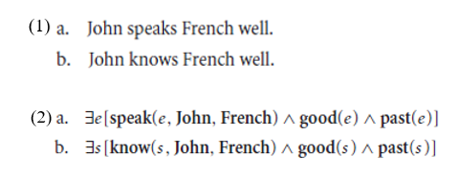

As we have seen, one of the ways in which manner modifiers of state verbs are interpreted is as degree modifiers. Indeed it is a puzzle that this should be the case: that so many adverbs that are interpreted as manner modifiers when they combine with event verbs should be reinterpreted as degree modifiers when they are combined with state verbs.1 This is not something we expect on a Davidsonian-style account. On the hypothetical Davidsonian analyses of (1a) and (1b) given in (2), we expect the adverb well to have a univocal interpretation.

We don’t expect well in (1a) to indicate the quality of speech, but well in (2b) to indicate the degree of knowledge. An important open question, then, concerns the source of this regular polysemy. To try to make sense of this question (and to make good on the claim we made above that the droppability of well follows from its degree-modifier semantics), we turn now to a discussion of degree modification.

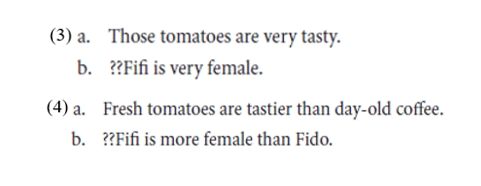

Degree modification is intrinsically tied to the notion of gradability. Traditionally, gradable adjectives, such as tasty or tall, have been distinguished from non-gradable adjectives, such as female and American (Bolinger 1972; Kamp 1975), gradable adjectives being those that accept degree modification and can appear in the comparative, and non-gradable adjectives being those that do not and cannot:2

Bolinger (1972) noted that, like adjectives, verbs can be classified as gradable and non-gradable. Gradable verbs can combine felicitously with the adverbial phrase very much and can be used in the comparative.

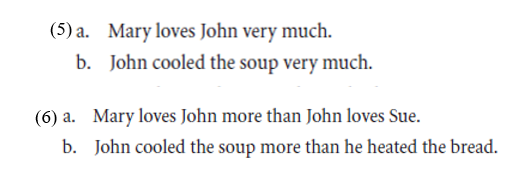

Non-gradable verbs are either degraded or have only a temporal interpretation3 when combined with very much or used in the comparative:

(7) a. She owns a car very much.

b. John hit Mary very much.

(8) a. John owns the house more than Mary owns the bike.

b. John hit Mary more than Mary hit John.

Stereotypical stative verbs such as love, know, want, desire, believe, depend, appreciate, and resemble are all gradable, while stereotypical event verbs such as hit, eat, notice, and arrive are all non-gradable. There is a small class of non-gradable state verbs, examples being own, contain, belong, consist of, and cost, and a small class of event verbs such as fill, empty, clean, cool, widen, and lengthen (the so-called “degree achievements” of Dowty 1979 and Kennedy and Levin, this volume) are gradable.

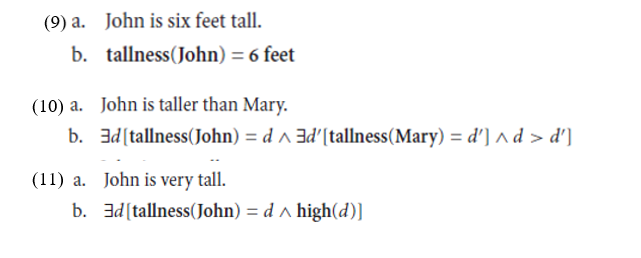

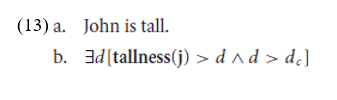

Turning now to semantics, degree modifiers are typically taken to be a type of predicate modifier whose interpretation makes reference to the abstract notion of the degree to which a predicate holds (Cresswell 1977; von Stechow 1984; Heim 1985; Kennedy 1999b, 2001; Kennedy and McNally 2005). On Kennedy’s (1999b, 2001) account, for example, gradable adjectives are interpreted as relations between individuals and degrees on a scale.4 The adjective tall, for example, relates individuals to their degree of tallness, and degree modification involves predication about or specification of this degree. In (9a), for example, the degree of tallness is specified explicitly, while in (10a) two degrees of tallness are compared, and in (11a) John’s degree of tallness is predicated to be high.

Formally, these modifiers are treated as functions from relations to relations, with existential closure applying after the application of the modifier. It is also frequently assumed that gradable predicates have a degree argument and that this argument is projected in the syntax (Abney 1987, Kennedy 1999b).

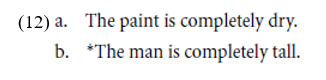

Degrees are, of course, ordered, and ordered sets of degrees are known as scales. The predicate high in (11b) and the ordering relation in (10b) are defined on the basis of the tallness scale, for example. Interestingly, Kennedy and McNally (2005) have shown that adjectives can be categorized on the basis of a number of semantic properties of their associated scales. The predicate tall is associated with a scale which has no maximal element (there is no maximal degree of tallness), while the predicate dry is associated with a scale which does have a maximal element. This contrast between scales with no maximum – “open” scales – and scales with a maximum – “closed” scales – is reflected in the distribution of the degree adverb completely, which appears only with closed-scale predicates:

In addition, gradable adjectives are typically associated with a standard of comparison, which serves to distinguish individuals that are in the extension of the given adjective from those that are not (Klein 1980; von Stechow 1984; Kennedy 2001). This is taken to be a specified degree on the scale, which is lexically specified. Kennedy and McNally distinguish two varieties of standards: contextual standards and absolute standards. The predicate tall has a contextual standard – to be tall is to be taller than some contextually specified height.5 For (13a) to be true, in a given context c it must be the case that John’s tallness exceeds a contextually determined standard for tallness dc (as indicated in 13b).

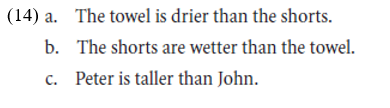

In contrast, predicates such as dry and wet have absolute standards. To be dry is to be maximally dry and to be wet is to be minimally wet. This distinction is evident from the entailments associated with comparative uses of the predicates. In (14a) the towel and the shorts cannot both be dry, in (14b) both of them must be wet, and in (14c) neither Peter nor John need be tall (but one or both might be).

Kennedy and McNally, then, classify gradable adjectives in terms of their associated scales and standards: the scale can be open (no maximum degree: tall, rich, far) or closed (there is a maximum degree: dry, healed, near) and the standard of comparison can be contextual (tall, poor, near), absolute-minimal (wet, scratched) or absolute-maximal (dry, flat).

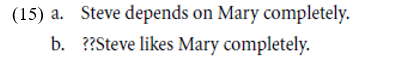

As one might expect, gradable verbs can similarly be classified on the basis of their associated scales and standards. In contrast to the scales associated with such concrete scalar adjectives as tall or short, the scales associated with state verbs are often quite abstract (the love scale, the desire scale, the knowledge scale), making it difficult to determine what properties these scales have. Is there a maximal degree of liking? Are the standards for knowing contextual or absolute? Fortunately such tests as the felicitous cooccurrence with the adverb completely and the entailments associated with the comparative serve as useful guides. As we see in (15), depend (on), which appears naturally with completely, seems to be associated with a closed scale, while like, which does not, appears to be associated with an open scale.

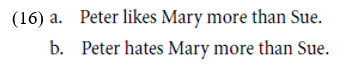

The verb like also appears to be associated with a contextually specified standard, contrasting with the verbs love and hate, which seem to be associated with minimal standards. This follows from the entailments associated with the comparative – (16a) can be true even if Peter doesn’t like either Mary or Sue, while (16b) can only be true if Peter hates both of them.

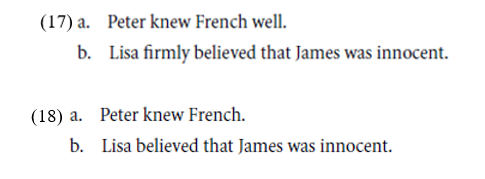

The verbs like, love, and know appear to be associated with open scales, while depend (on) and understand are associated with closed scales; like and know are associated with a contextual standard, while hate and understand are associated with absolute-minimal and absolute-maximal standards, respectively. We can now account for the fact that the “manner” modifiers well and firmly are both droppable – with (17a, b) entailing (18a, b).

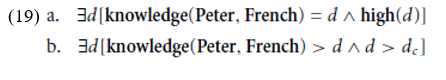

This follows directly from the fact that both know and believe are associated with contextual standards, and the degree adverbs well and firmly indicate that the standard of comparison is shifted up the scale. In the case of well, for example, to know someone well is to have a high degree of knowledge of that person and to have a high degree of knowledge of that person is typically to have a degree that is above the contextually specified standard associated with know. The analyses of (17a) and (18a), given in (19) illustrate this.

On the assumption that high(d) > dc it follows that (19a) entails (19b). Note that a degree adverb such as slightly would shift the standard down below the contextual standard, capturing the fact that to know someone slightly is not to know that person, and thus that slightly cannot be dropped.

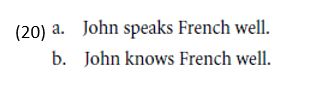

Let us return to the question of why adverbs such as firmly or well, which clearly have a manner interpretation when combined with event verbs, have degree interpretations when combined with state verbs. One suggestion is that this is a form of polysemy similar to that with which we are already familiar. If we are correct that speak and know differ in their syntactic structure, with speak having an event argument and know having a degree argument, then perhaps the contrast in the interpretation of well in (20) is very much like the syntactically determined polysemy of disgustingly discussed above.

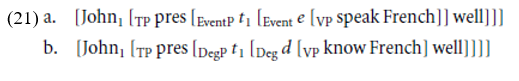

Concretely, we can speculate that well is simply associating with different projections in (20a) than it is in (20b), as illustrated in (21).

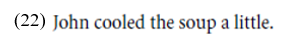

Of course non-gradable state predicates will lack the degree projection, and (more interestingly) gradable event predicates will have both an event projection and a degree projection, accounting for the ambiguity of such sentences as (22).

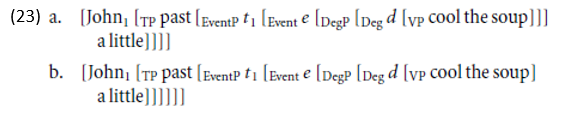

On one intepretation the degree modifier a little associates with the event and on the other with the degree, as indicated in (23).

This account in (21) is, of course, not available if state verbs and event verbs both have Davidsonian arguments and both project the same kind of syntactic superstructure.

1 Herwig (1998) documents a historical process of manner to degree shift in English.

2 Non-gradable predicates can often be reinterpreted as such, so while dead, alive, and female Don’t really admit of degrees, we sometimes use degree modifiers or comparative forms of these metaphorically, as in (i).

(i) She is very female.

“She is very feminine.”

3Temporal readings are those in which the number of times is what is being measured or compared. For reasons that are not clear, for state verbs temporal readings are more remote than for event verbs. Note that for comparative adjectives these readings are clearly distinguished syntactically:

(i) a. John is more sick than Mary is. [degree-comparison]

b. John is sick more then Mary is. [time-comparison]

4 Analyses of gradable event verbs are similar. Parsons (1990), explicitly rejecting a Davidsonian account of degree adverbs, takes partially to be interpreted as an operator that takes predicates of events and returns predicates of partial events of the same type. More detailed analyses have been given by Hay, Kennedy and Levin (1999) and more recently by Caudal and Nicolas (2005), and Pinon (2005).

5 The well-known context-dependence of such adjectives (Kamp 1975) is thus addressed – tall in tall basketball player is typically associated with a different standard than tall in tall jockey.

|

|

|

|

دراسة: حفنة من الجوز يوميا تحميك من سرطان القولون

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

تنشيط أول مفاعل ملح منصهر يستعمل الثوريوم في العالم.. سباق "الأرنب والسلحفاة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي يقيم دورة تطويرية عن أساليب التدريس ويختتم أخرى تخص أحكام التلاوة

|

|

|