Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-10-01

Date: 2024-09-13

Date: 2024-09-30

|

Intellectually blank assertions are deadly for the reader because they do not anchor his mind, they are not stimulating to read, and they present the very real danger that he will not in fact grasp what you are trying to say. To illustrate, here is an exchange I heard on the radio several years ago:

First Speaker

John Wain says he believes he is well placed to write

this biography of Samuel Johnson for three reasons:

The same poor Staffordshire background

The same education at Oxford

The same literary preferences.

Second Speaker

I don't agree. There are no real truths in Staffordshire.

Then everybody laughed and the speakers went on to talk about something else. I thought, "I don't believe I heard that." Because look what happened. There you sit, waiting for an idea to be communicated, but instead you get an intellectually blank assertion ("for three reasons"). No idea yet. When you hear, "The same poor Staffordshire background ...," you assume it is the speaker's main point, and you barely listen to the other two points. So that if you were to reply, you'd reply to the point that you heard.

If instead the first speaker had said something like…

John Wain says he is well placed to write this biography of Samuel Johnson

because he and Johnson are essentially the same kind of people .

. . . then while you would have had to listen to the supporting points, you would have replied to the point that you heard. Instead, you have people absolutely talking past each other.

I have just illustrated what I mean by a summary point. You can see that your mind is marginally more ready to take in the information that follows if you hear "He did it because they are the same kind of people" than if you hear "He did it for three reasons." The second point sounds dead, it in fact is dead, and a document studded with such intellectually blank assertions is unbelievably boring to read.

But there is an even more important reason for avoiding intellectually blank assertions, and that is that they cover up incomplete thinking, and thus cheat you out of a wonderful opportunity to move your thinking forward in an orderly and creative way. One of the major values of formally summarizing a grouping is that it inevitably stimulates further thinking. Because once you have derived an insight, you are free intellectually to carry it forward in one of two ways:

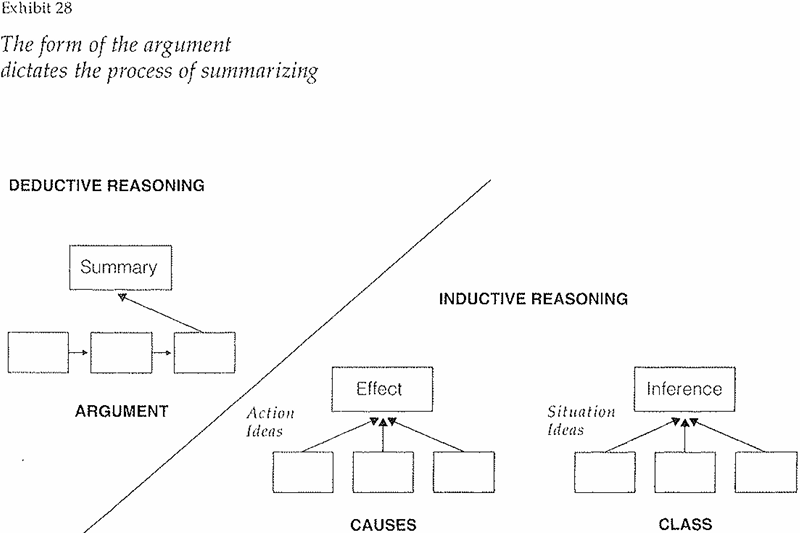

By commenting further on it (deduction)

By finding others like it (induction)

But you must have a true summary statement derived from a proper grouping before the process can yield new insights (Exhibit 26).

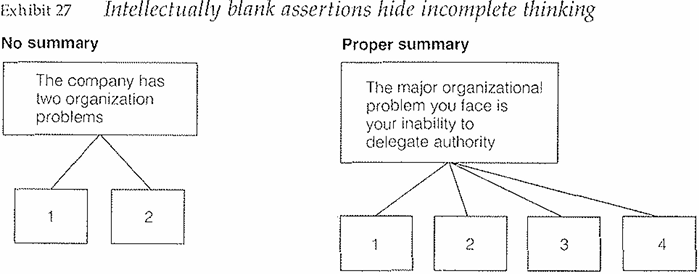

To illustrate, I once worked with someone who wrote, "The company has two organization problems," and then listed the two problems. The statement is intellectually blank, so he knew it had to be rewritten. And that would be easy to do provided the ideas grouped below were (a) both organization problems and (b) had a logical order. We could not find a logical order.

When pressed to state where the ideas came from and how they were alike, he discovered that in fact he wasn't talking generally about "organization problems." He was talking specifically about "areas of the organization where greater delegation is needed." Once he saw that, he realized that there were not two of these so-called problem areas, but four, only one of which he had properly identified. He was then able to realize the insight that the major organization problem the company faced was its inability to delegate authority (Exhibit 27). Now, having clearly identified the problem, he was free to focus his thinking on finding a solution to it.

For these reasons it is important that you make the effort to derive proper summary statements from your groupings. What does that mean you should do? First, as it was shown, you have to check the origin of the grouping to make sure it is MECE (i.e., that its order reflects a valid process, structure, or classification). Then you need to look at the kind of statement you are making.

Regardless of the origin of the idea, its expression will be either as an action statement, telling the reader to do something, or as a situation statement, telling the reader about something.

- Summarize the action ideas by stating the effect of carrying out the actions

- Summarize the situation ideas by stating what their being similar implies.

As Exhibit 28 illustrates, summarizing inductive groupings means either stating the effect of actions or drawing an insight from conclusions.

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اتحاد كليات الطب الملكية البريطانية يشيد بالمستوى العلمي لطلبة جامعة العميد وبيئتها التعليمية

|

|

|