Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

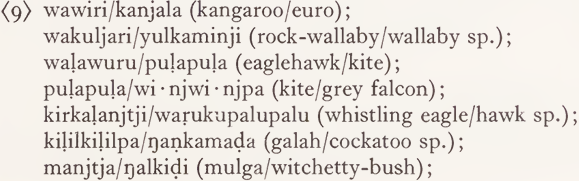

A note on a Walbiri tradition of antonymy

المؤلف:

KENNETH HALE

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

472-26

2024-08-21

1026

A note on a Walbiri tradition of antonymy

This paper will be concerned with a particular linguistic tradition learned by Walbiri men at a certain point in their integration into ritual life.1 The Walbiri are an aboriginal people of Central Australia now living on several settlements and cattle stations distributed over a rather vast area in the western part of the Northern Territory. They have received no little attention from anthropologists, and there exists an excellent account of their society by M. J. Meggitt (1962). My own work with the Walbiri has been primarily linguistic. But, in the Walbiri community, it becomes immediately evident that much of what is observed in linguistic usage is intimately related to such cultural spheres as kinship and ritual.

The linguistic tradition with which I will be concerned here is associated with advanced initiation rituals of the class which the Walbiri loosely refer to as kankalu (‘high, above’), a general term embracing the katjiri described by Meggitt in a recent monograph (Meggitt, 1967) and a set of about seven ritual complexes termed waduwadu (or kumpaltja) by the Walbiri at Yuendumu. The linguistic remarks which follow should not, perhaps, be generalized beyond the Yuendumu Walbiri or beyond the waduwadu subclass of kankalu rituals; however, Walbiri men have asserted that they are valid for all Walbiri and for all kankalu.

Before continuing, I must ask the reader to cooperate with a specific condition which Walbiri men place on material of this sort. All knowledge relating centrally to kankalu ritual is exclusively the property of men who have gone through the rituals. While many Walbiri are eager to have the material recorded and published as a matter of scientific record, they request strongly that it be handled with care. Specifically, they request that none of the knowledge be discussed with uninitiated Walbiri men or with Walbiri women and children. If the reader should have an opportunity to discuss the material in this note with a Walbiri man, it is important that he first determine that the man concerned is a maliyara and that he is willing to discuss matters relating to kankalu ritual.

Walbiri youths normally become junior kankalu novices shortly after their first initiation, i.e., shortly after circumcision (at an average age of 13). And it is in the context of their first kankalu novitiate that they acquire the linguistic skills to be described in the following paragraphs.

Men who are advanced in kankalu ritual are referred to as maliyara, a term widespread in Central and Northwestern Australia. But they are also referred to as tjiliwiri, a term which in its profane usage means ‘funny’ or ‘clown’. The term tjiliwiri is also extended to refer specifically to formalized ‘clowning ’ during kankalu ritual and to the men who serve as guardians of junior kankalu novices.

It is another extension of this term that is relevant here. In apparent close association with the concept of ritual clowning is a type of semantic pig-Latin spoken by guardians in the presence of junior novices. This is also referred to as tjiliwiri and will be so designated in what follows. It is a ‘secret language’ in the sense that it is spoken, theoretically, and probably in fact, only in the context of kankalu ritual and beyond the hearing of uninitiated Walbiri.

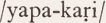

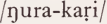

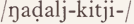

Walbiri men sometimes refer to tjiliwiri as ‘up-side-down Walbiri’. They say that, to speak tjiliwiri, one turns ordinary Walbiri ‘up-side-down’ (ŋadalj-kitji-ni), a skill which junior novices are expected to acquire by observation while they are in seclusion in connection with their first kankalu involvement.

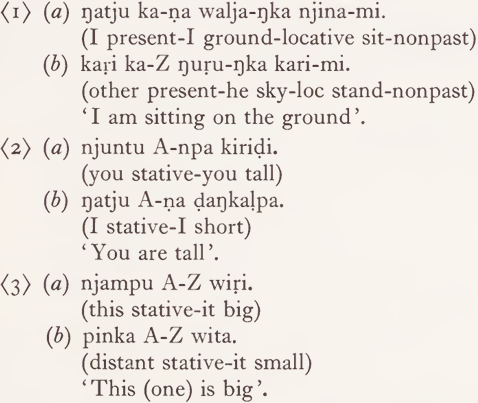

In very general terms, the rule for speaking tjiliwiri is as follows: replace each noun, verb, and pronoun of ordinary Walbiri by an ‘antonym’. Thus, for example, if a tjiliwiri speaker intends to convey the meaning ‘ I am sitting on the ground ’, he replaces ‘ I ’ with ‘ (an)other ’, ‘ sit ’ with ‘ stand ’, and ‘ ground ’ with ‘ sky ’. Similarly, if he intends to convey the meaning ‘ You are tall ’, he replaces ‘ you ’ with ‘I’, and ‘tall’ with ‘short’. To illustrate, I cite simple sentences in Walbiri (the (a)-form) together with their tjiliwiri equivalents (the (b)-forms) and their English translations.2

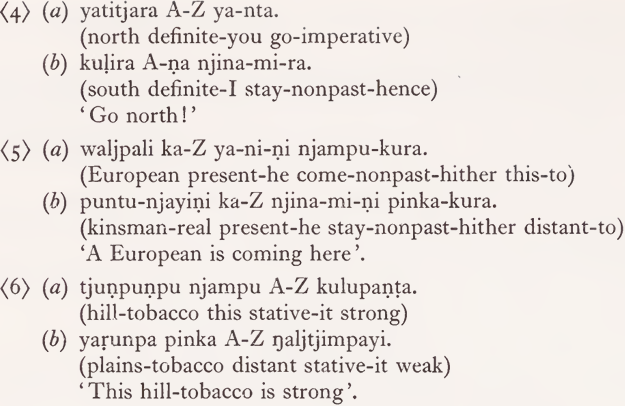

Ordinary Walbiri is spoken rapidly, and apparently, tjiliwiri speech is equally fast. Novices are not taught the semantic principle directly; rather, they must learn it by observation. According to my consultants, the novices are exposed to rapid dialogues between guardians. In these dialogues, one guardian speaks tjiliwiri while the other answers, or rather interprets the message, in Walbiri. Each exchange in the dialogue is punctuated by the expletive yupa, an exclusively tjiliwiri word. In the following illustrative dialogue, the first individual, A, speaks tjiliwiri, and the second, B, responds in Walbiri. The free translation of the tjiliwiri speech represents the intended message; the parenthetic gloss is literal.

Novices are said to learn to speak and understand tjiliwiri in two to four weeks. Walbiri men stated that when they first heard tjiliwiri, its principle eluded them for some time; eventually, they explained, it came as a sudden flash of insight. I would like now to consider briefly the nature of this principle and, in particular, the problem of determining a possible tjiliwiri antonym of a given Walbiri lexical item.

An obvious antonymy principle is that of polarity, i.e., the principle involved in oppositions of the type represented by English good/bad, big/little, strong/weak. This principle is used wherever possible to determine tjiliwiri equivalents, as in:

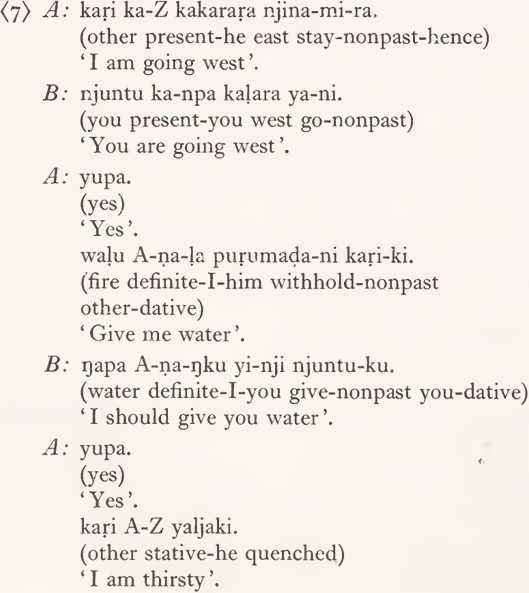

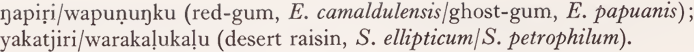

It is evident, however, that the rather obvious and very suggestive polarity principle of antonymy is unsuited to many lexical domains. Within the tjiliwiri tradition, polarity is simply a special case of a vastly more general principle. Consider, for example, lexical items whose semantic interrelationships are typically taxonomic:

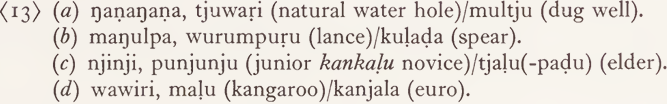

It is apparent that the principle employed here is that of opposing entities which, according to some taxonomic arrangement or other, are most similar, i.e., in formal terms, entities which are immediately dominated by the same node in a taxonomic tree. Thus, members of a given class of objects are opposed to other members of the same immediate class - a large macropod is opposed to another large macropod (kangaroo/euro), a eucalypt is opposed to another eucalypt (red-gum/ghost-gum), and so on. A great deal of variability can be observed in lexical domains whose structure is taxonomic, since considerable latitude is permitted in the hierarchical arrangement of oppositions within well defined classes. Accordingly, on a given occasion, a tjiliwiri speaker may oppose macropods according to habitat, leaving size and other attributes constant insofar as it is possible to do so; on another occasion, he may oppose them on the basis of size, leaving constant the other attributes. In general, however, an effort is made to oppose entities which are minimally distinct. The accuracy with which a tjiliwiri speaker is able to do this determines the ease with which his dialogue partner will be able to interpret the message.

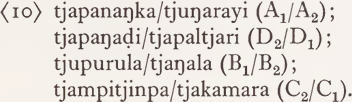

Consider now the principle employed in opposing the Walbiri subsection terms:

The parenthetic glosses here are the traditional ones employed in the anthropological literature (e.g., Meggitt, 1962, pp. 164-87). These subsections are arranged in more inclusive groupings: there are two patrimoieties (AD, BC), two matrimoieties (AC, BD), two merged alternate generation moieties (AB, CD), and four sections (A1 D2, D1 A2, B1 C1, B2 C2). There exists a system of terminology corresponding to each of these groupings. It can be seen that the tjiliwiri opposite of a given subsection X is that subsection Y whose members belong simultaneously to the same patri-, matri-, and merged alternate generation level moieties as the members of X. Equivalently, the tjiliwiri opposite of X is that subsection Y whose members (collectively) are distinct from those of X solely on the basis of section membership (i.e., in biologically based terms, on the basis of agnation). Furthermore, it is obvious that section membership (or agnation) is the only dimension which can minimally oppose subsection terms, a fact that requires some contemplation to appreciate. By any pairing other than the actual tjiliwiri one, the paired terms differ in at least two dimensions. This and the earlier examples indicate that minimal opposition is basic to the tjiliwiri principle of antonymy.

Kinship terms, as in (11), are opposed on the basis of seniority and generation (ascending as opposed to descending). The two principles are complementary, since the first is relevant only within Ego’s generation, the second only relative to Ego’s generation:

Notice that if an equally operative principle such as cross/parallel (cf. Kay, 1965) were employed, it would not be possible to oppose all kinship terms minimally - i.e., it is not possible to pair Walbiri kinship terms in such a way that the members of each pair are distinct only on the cross/parallel dimension. To be sure, there is at least one other distinction which could serve to oppose Walbiri kinship categories minimally, namely, sex antonymy. However, if sex of kinsman were used here, it would violate an apparent requirement that tjiliwiri opposites be phonologically distinct. While sex antonymy plays an important role in the Walbiri terminology, it is defective, and many categories which are distinct only on the sex dimension are represented by a single, phonologically unified kinship term (e.g., /qalapi/ (So, Da), /tjatja/ (M0M0, MoMoBr), etc.).

The observation just made leads to another one which reveals rather well the abstract nature of the tjiliwiri activity. It could conceivably be argued that phonologically unified elements of the type represented by /ŋalapi/ (So, Da) are not semantically ambiguous in the way I have implied; i.e., one might argue that the term /ŋalapi/ is simply the name for the class of Ego’s agnates in the first descending generation and that the principle of sex antonymy plays no role at that point in the Walbiri kinship system. We know that this is not the case, since the kinship system as a whole requires recognition of a class of male /ŋalapi/ as opposed to a class of female /ŋalapi/ - this is shown, e.g., by the fact that the offspring of Ego’s male /ŋalapi/ are his parallel (in fact, agnate) kinsmen, while the offspring of his female /ŋalapi/ are not; furthermore, there is a technical usage according to which the female, but not the male /ŋalapi/ is referred to by the special term /yuṇṭtalpa/ (cf. Meggitt, 1962, p. 115). The male and female /ŋalapi/ are clearly distinct in tjiliwiri usage - the male is opposed to /kidana/ (Fa), while the female is opposed to /pimiḍi/ (FaSi). And, in general, polysemy is reflected in tjiliwiri practice:

As expected, synonymy is also reflected :

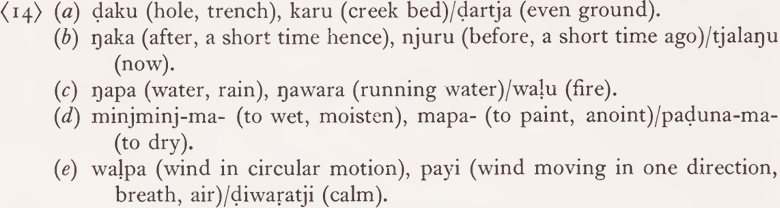

It is clear from these examples that the tjiliwiri principle of antonymy is semantically based, i.e., that the process of turning Walbiri ‘up-side-down’ is fundamentally a process of opposing abstract semantic objects rather than a process of opposing lexical items in the grossest and most superficial sense. This abstract nature of the tjiliwiri activity is particularly evident in cases of the type represented by (14 a-e) in which an opposition reflects the partial synonymy of lexical items - that is, cases in which one semantic object is opposed to another which enters into the make-up of two distinct though semantically related lexical items:

It is, of course, not surprising that tjiliwiri is semantically based in the particular sense that it makes use of abstract semantic structures - it would be difficult, otherwise, to conceive of how an individual could learn the system in a relatively short time, through exposure to a severely limited and highly unsystematic sample of actual speech. It is abundantly clear that a general principle is learned and that, once acquired, the principle enables the learner to create novel tjiliwiri sentences and to understand any well-formed novel sentence spoken by another. This general principle of antonymy is determined by a semantic theory which we know, on other grounds, must be shared by the speakers of Walbiri. The tjiliwiri activity provides us with a surprisingly uncluttered view of certain aspects of this semantic theory and is certainly not irrelevant to the much discussed, though occasionally incoherent, question of whether the semantic structures we, as students of language or culture, imagine to exist do, in fact, have any ‘ reality ’ for the speakers who use the system. In this connection, it is interesting to note that the semantic relationships which tjiliwiri reveals are not inconsistent with semantic structures which have been recognized throughout the history of semantic studies - these include not only such obvious concepts as polarity, synonymy, and antonymy, but also the more general conception that semantic objects are componential in nature, that lexical items often share semantic components and belong to well defined domains which exhibit particular types of internal structure (e.g., the tanoxomic structure of the biological and botanical domains; the paradigmatic structure of the kinship domain; and so on). None of these observations is surprising, to be sure, given the semantic basis of tjiliwiri, but it is rather supportive to learn that even very specific principles, postulated on independent grounds, are actively manipulated in tjiliwiri - e.g., the principle of agnatic kinship, generation antonymy, and the like.

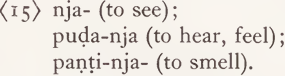

Abstract systems of relationship among lexical items are reflected in a particularly striking manner in certain cases. Consider, for example, the conception (whose validity is apparent on a variety of grounds - semantic, syntactic, and morphological) that the Walbiri verbs of perception belong to a special lexical subset:

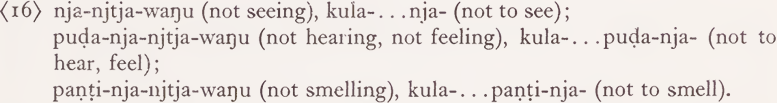

What is of interest here is the fact that an important aspect of the internal structure of this lexical subset can be revealed, in standard Walbiri usage, only by recourse to a syntactic device, i.e., negation. The abstract semantic structure of the subset must provide that each of the three perception verbs be paired by an antonym - it is relatively apparent that the three verbs cannot themselves be contrasted with one another in any way which is obviously consistent with the principle of minimal opposition. In a rather clear sense, then, the Walbiri domain of perception contains six terms, rather than three - in other words, it contains three pairs of opposed terms. Since Walbiri has no standard antonyms for the perception verbs, the domain is lexically defective and is completed only by negating the existing forms in one way or another:

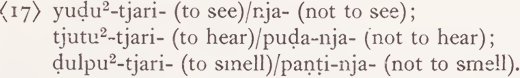

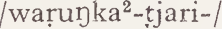

This recourse is not available in tjiliwiri, however, due to the general convention that the negative may not be used to create tjiliwiri opposites. In cases where Walbiri lacks a suitable antonym for a particular lexical item, an opposite must be coined for tjiliwiri. In tjiliwiri, the class of perception verbs is complete in the sense that it corresponds more or less exactly to what we have reason to assume is the actual abstract structure of the lexical subset:

Notice further that the internal cohesion of the domain is preserved in the form of the tjiliwiri coinages - i.e., all share the morphological peculiarity that they are composed of a reduplicated root preposed to the verbal formative /-tjari-/ (inchoative).3

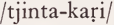

attests to the abstractness of tjiliwiri antonymy.4 In ordinary Walbiri usage,  is not a free form but a suffix, and was apparently abstracted for tjiliwiri from its function in such standard Walbiri expressions as

is not a free form but a suffix, and was apparently abstracted for tjiliwiri from its function in such standard Walbiri expressions as  (one-other) ‘another’,

(one-other) ‘another’,  (person-other) ‘another person’,

(person-other) ‘another person’,  (place-other) ‘another place ’. Another example of this same general type is found in the tjiliwiri treatment of the demonstrative determiners. The standard Walbiri forms are: /njampu/ ‘ this ’; /yalumpu/ ‘that near addressee, that near’; /yali/ ‘that away from speaker and addressee, that distant’; /yinja/ ‘that beyond field of reference, that ultra-distal’. From this set, tjiliwiri abstracts the proximate-nonproximate dimension and represents it by means of the opposition entailed in the pair /pinka/-/kutu/ (far-near). Standard Walbiri /njampu/ and /yalumpu/, both ‘proximate’, are represented in tjiliwiri by the single form /pinka/ (far). What is clearly involved here is a semantic analysis of the Walbiri paradigm; the tjiliwiri opposition is based on the abstract dimensions inherent in that analysis - i.e., /pinka/ represents the abstract proximity feature shared by /njampu/ and /yalumpu/. The abstractness of this representation, as in the case of

(place-other) ‘another place ’. Another example of this same general type is found in the tjiliwiri treatment of the demonstrative determiners. The standard Walbiri forms are: /njampu/ ‘ this ’; /yalumpu/ ‘that near addressee, that near’; /yali/ ‘that away from speaker and addressee, that distant’; /yinja/ ‘that beyond field of reference, that ultra-distal’. From this set, tjiliwiri abstracts the proximate-nonproximate dimension and represents it by means of the opposition entailed in the pair /pinka/-/kutu/ (far-near). Standard Walbiri /njampu/ and /yalumpu/, both ‘proximate’, are represented in tjiliwiri by the single form /pinka/ (far). What is clearly involved here is a semantic analysis of the Walbiri paradigm; the tjiliwiri opposition is based on the abstract dimensions inherent in that analysis - i.e., /pinka/ represents the abstract proximity feature shared by /njampu/ and /yalumpu/. The abstractness of this representation, as in the case of  above, is evidenced further by the fact that a grammatical readjustment is required - the forms /pinka/ and /kuta/, which of all Walbiri forms permit perhaps the most direct and unencumbered reference to the semantic opposition proximate-nonproximate, are adverbials, not determiners in standard Walbiri usage.

above, is evidenced further by the fact that a grammatical readjustment is required - the forms /pinka/ and /kuta/, which of all Walbiri forms permit perhaps the most direct and unencumbered reference to the semantic opposition proximate-nonproximate, are adverbials, not determiners in standard Walbiri usage.

The existence of auxiliary speech-forms in Australia is well known (see, for example, Robert Dixon’s detailed account of the so-called mother-in-law language elsewhere in this volume), but the particular form represented by tjiliwiri has, to my knowledge, not been reported. Unfortunately, I am able to give only a brief account of this form due to the circumstance that I did not become aware of its existence until I was invited to attend the  initiation at Yuendumu in 1967, very near the end of my stay there. Since I was at that time involved in an intensive study of Walbiri syntax, which required most of my attention, I was able to investigate tjiliwiri to an extremely limited extent only. Nonetheless, I believe the material to be of sufficient interest to warrant this preliminary report, particularly in view of the fact that an extensive study is still very much possible in the Walbiri community.

initiation at Yuendumu in 1967, very near the end of my stay there. Since I was at that time involved in an intensive study of Walbiri syntax, which required most of my attention, I was able to investigate tjiliwiri to an extremely limited extent only. Nonetheless, I believe the material to be of sufficient interest to warrant this preliminary report, particularly in view of the fact that an extensive study is still very much possible in the Walbiri community.

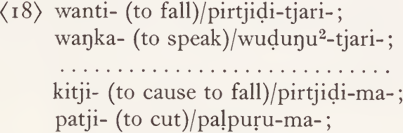

The theoretical potential of tjiliwiri is rather obvious. I have indicated a number of ways in which it reveals aspects of the semantic structure shared by speakers of Walbiri - typically, it confirms observations which can be made in the course of conventional grammatical and semantic analysis, but occasionally it reveals categories which are by no means obvious. For example, it would appear, superficially, that the use of the verbalizing suffixes /-tjari-/ (inchoative) and /-ma-/ (causative, transitive) in tjiliwiri coinages, is determined by the purely syntactic transitivity of the Walbiri equivalent:

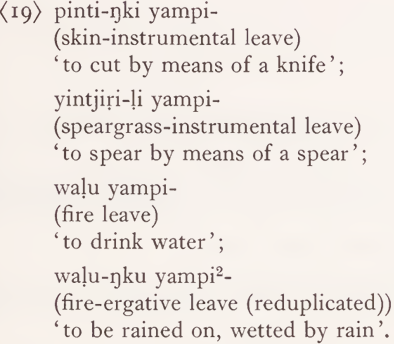

with /-tjari-/ forming intransitives and /-ma/ forming transitives. It appears, however, that the use of these suffixes is determined by a factor which is much less apparent than this. Thus, /-ma-/ forms transitive verbs of affecting - i.e., verbs denoting actions which produce effects upon the entities denoted by their objects. While it is true to say that /-tjari-/ forms intransitives, the suffix is also used in forming tjiliwiri equivalents of verbs which are syntactically transitive in Walbiri but which are not verbs of affecting in the above sense (e.g., the perception verbs of (17) - the object of perception is not ‘ affected ’ in any sense akin to that in which the object of, say, cutting is ‘affected’). This is not the only way in which this elusive and covert category is reflected in tjiliwiri usage. The entire class of verbs of affecting, and only those, can be opposed to the single verb /yampi-/ ‘ to refrain from affecting, to leave alone ’. That is, where the context is sufficiently clear, it is possible to abstract the feature shared by all verbs of affecting and represent it by its opposite /yampi-/, as in expressions like:

The examples which I have used in this brief account illustrate the potential relevance of the tjiliwiri activity to the study of purely linguistic matters. There is, however, another aspect of the tradition which I have not touched on but which promises to be of considerable anthropological interest. The majority of Walbiri- tjiliwiri equivalences conform to a general principle of antonymy which is relatively consistent throughout and which can be characterized in terms of highly familiar, universal semantic notions - this is the principle which Walbiri speakers refer to by the term  ‘to invert, turn over, reverse’. There remain, however, many oppositions which can be fully understood only in reference to other aspects of Walbiri culture. The opposition of fire and water, for example, an opposition which is not uncommon elsewhere in the world, is an important theme in Walbiri ritual and epic. Many of the most important epics have an episode relating to fire, or burning, and another relating to rain, or flooding. In taboo-laden and culturally loaded areas, equivalences are, from the strictly linguistic point of view, idiosyncratic - e.g., the oppositions:

‘to invert, turn over, reverse’. There remain, however, many oppositions which can be fully understood only in reference to other aspects of Walbiri culture. The opposition of fire and water, for example, an opposition which is not uncommon elsewhere in the world, is an important theme in Walbiri ritual and epic. Many of the most important epics have an episode relating to fire, or burning, and another relating to rain, or flooding. In taboo-laden and culturally loaded areas, equivalences are, from the strictly linguistic point of view, idiosyncratic - e.g., the oppositions:  (semen, coitus/mulga seed); kuna/wamulu (excrement/animal or vegetable down used in ritual decoration);

(semen, coitus/mulga seed); kuna/wamulu (excrement/animal or vegetable down used in ritual decoration);  (shield, circumcision ground/blue-tongue lizard);

(shield, circumcision ground/blue-tongue lizard);  (always, eternally/ totem center); kuyu/tjutju (animal, meat/sacred object, dangerous entity, useless object or material). Although each individual equivalence in such cases may not be explainable in terms of a single general principle, it is unlikely that the segment of the vocabulary which exhibits this seemingly idiosyncratic behavior is itself an arbitrary assemblage of lexical items. Rather universal considerations of taboo (cf. Leach, 1964) may well make it possible to predict which Walbiri terms will have idiosyncratic equivalents in tjiliwiri - e.g., /maliki/ ‘dog’, an animal living in close association with humans, is paired idiosyncratically with /tjatjina/ ‘crest- tailed marsupial mouse’, while wild animals are opposed according to general taxonomic principles. Furthermore, it is most likely that individual associations of this type can be explained in terms of highly general, nonlinguistic, principles of opposition of the sort studied by Levi-Strauss (Levi-Strauss, 1964).

(always, eternally/ totem center); kuyu/tjutju (animal, meat/sacred object, dangerous entity, useless object or material). Although each individual equivalence in such cases may not be explainable in terms of a single general principle, it is unlikely that the segment of the vocabulary which exhibits this seemingly idiosyncratic behavior is itself an arbitrary assemblage of lexical items. Rather universal considerations of taboo (cf. Leach, 1964) may well make it possible to predict which Walbiri terms will have idiosyncratic equivalents in tjiliwiri - e.g., /maliki/ ‘dog’, an animal living in close association with humans, is paired idiosyncratically with /tjatjina/ ‘crest- tailed marsupial mouse’, while wild animals are opposed according to general taxonomic principles. Furthermore, it is most likely that individual associations of this type can be explained in terms of highly general, nonlinguistic, principles of opposition of the sort studied by Levi-Strauss (Levi-Strauss, 1964).

Despite the serious ritual associations of tjiliwiri, Walbiri men consider it proper to enjoy it thoroughly. They derive much pleasure from it. When I began to understand the principle, I remarked to one Walbiri man: ‘You certainly have something here! ’ He replied: ‘Indeed we have! ’

1 This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation (NSF Grant No. GS-1127) and in part by the National Institutes of Health (Grant MH-13390-01).

My debt to the Walbiri people is immeasurable, and I am particularly grateful to those Walbiri men who brought the tjiliwiri activity to my attention. I hope that some day they will be able to derive some benefit from my exploitation of their linguistic knowledge.

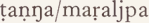

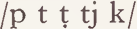

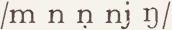

2 The alphabetic notation used in the examples has the following values: bilabial, apico-alveolar, apico-domal, lamino-alveolar, and dorso-velar stops  ; nasals matching the stops in position of articulation

; nasals matching the stops in position of articulation  ; laterals matching the non-peripheral stops and nasals

; laterals matching the non-peripheral stops and nasals  ; plain and retroflexed flaps

; plain and retroflexed flaps  ; bilabial, apico-domal, and lamino-alveolar glides

; bilabial, apico-domal, and lamino-alveolar glides  ; and vowels: high front /i/, high back (rounded) /u/, low central /a/. Nominal and verbal words are stressed on the first syllable; the clitic auxiliaries (e.g.,

; and vowels: high front /i/, high back (rounded) /u/, low central /a/. Nominal and verbal words are stressed on the first syllable; the clitic auxiliaries (e.g.,  ‘present-1’) are unstressed, though written as separate words in the examples. Some auxiliary stems are phonologically vacuous - these are represented by A in parenthetic glosses. The auxiliaries are inflected for person; the third person singular person markers, and the second person singular in imperatives, are phonologically null - these are represented by Z(ero) in the glosses.

‘present-1’) are unstressed, though written as separate words in the examples. Some auxiliary stems are phonologically vacuous - these are represented by A in parenthetic glosses. The auxiliaries are inflected for person; the third person singular person markers, and the second person singular in imperatives, are phonologically null - these are represented by Z(ero) in the glosses.

3 The etymologies of the tjiliwiri perception verbs, except for /tjutu2-tjari/, are not altogether clear. The form /tjutu/ refers to stoppage, closure, and to deafness. The form  is sometimes used in tjiliwiri in place of /tjutu2-tjari-/. The form

is sometimes used in tjiliwiri in place of /tjutu2-tjari-/. The form  refers to deafness, heedlessness, and to one form of insanity.

refers to deafness, heedlessness, and to one form of insanity.

4 The tjiliwiri equivalent of Walbiri /njuntu/ ‘you’ is /ŋatju/ ‘I’. That is, second person is opposed to first person. This principle is sometimes extended to Walbiri /ŋatju/ as well - i.e., in place of the ego-alter principle normally used.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)