Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

DEVIATIONS FROM GRAMMATICALITY

المؤلف:

URIEL WEINREICH

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

324-18

2024-08-08

1392

DEVIATIONS FROM GRAMMATICALITY

In the literature on generative grammar, the distinction between grammatical and other kinds of deviance occupies a privileged position, since the very definition of grammar rests on the possibility of differentiating grammatical from ungrammatical expressions. Since ungrammatical formations are a subclass of the class of odd expressions, the difference between ungrammaticality and other kinds of oddity must be represented in the theory of language.

But the problem exemplified by grammatically faultless, yet semantically odd expressions such as colorless green ideas has an old history. For two thousand years linguists have striven to limit the accountability of grammar vis-a-vis abnormal constructions of some kinds. Apollonios Dyskolos struggled with the question in second century Alexandria; Bhartrhari, in ninth century India, argued that barren woman's son, despite its semantic abnormality, is a syntactically well-formed expression. His near-contemporary in Iraq, Sibawaihi, distinguished semantic deviance (e.g. in I carried the mountain, I came to you tomorrow) from grammatical deviance, as in qad Zaidun qâm for qad qâm Zaidun ‘ Zaid rose ’ (the particle qad must be immediately followed by the verb).

The medieval grammarians in Western Europe likewise conceded that the expression cappa categorica ‘categorical cloak’ is linguistically faultless (congrua), so that its impropriety must be elsewhere than in grammar.1 The continuing argument in modern philosophy has a very familiar ring.2

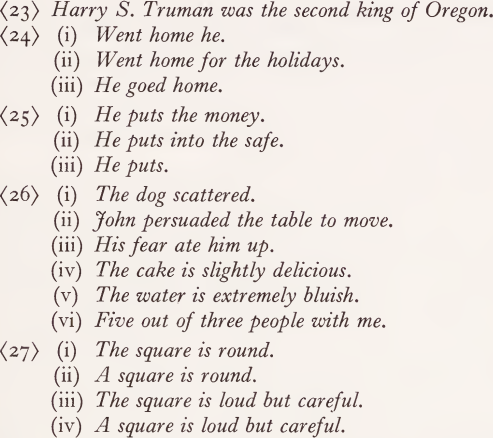

The position taken by most writers on generative grammar seems to rest on two planks: (a) grammatical oddity of expressions is qualitatively different from other kinds of oddity; and (b) grammatical oddity itself is a matter of degree. Let us consider these two points, in relation to the following examples:

We are not concerned here with any theories of reference which would mark sentence (23) as odd because of its factual falsity; on the contrary, we may take (23) as an example of a normal sentence, in contrast with which those of (24)-(27) all contain something anomalous. The customary approach is to say that (24)-(26) are deviant on grammatical grounds, while the examples of(27) are deviant on semantic grounds. This judgment can be made, however, only in relation to a given grammar G(L) of the language L; one may then cite the specific rules of G(L) which are violated in each sentence of (24)-(27), and indicate what the violation consists of. Whatever rules are violated by (27), on the other hand, are not in G(L); presumably, they are in the semantic description of the language, S(L). But as appeared, the demarcation between G(L) and S(L) proposed by KF is spurious, and no viable criterion has yet been proposed.3

In the framework of a theory of syntax in which subcategorization was represented by rewriting rules of the phrase-structure component of a grammar, Chomsky (cf. Miller and Chomsky 1963: 444 b) proposed to treat degrees of grammaticality roughly in the following way.4 Suppose we have a grammar, G0, formulated in terms of categories of words W1, W2, ... Wn. We may now formulate a grammar G1 in which some categories of words - say, Wj and Wk - are treated as interchangeable. A grammar G2 would be one in which a greater number of word categories are regarded as interchangeable. The limiting case would be a ‘grammar’ in which all word classes could be freely interchanged. Expressions that conform to the variant grammar Gi would be said to be grammatical at the i level. But it is important to observe that nowhere in this approach are criteria offered for setting up discrete levels; we are not told whether a ‘ level ’ should be posited at which, say, W1 is confused with W2 or W2 with W3; nor can one decide whether the conflation of W1 and W2 takes place at the same ‘ level ’ as that, say, of W9 and W10, or at another level. The hope that a quantative approach of this type may lead to a workable reconstruction of the notion of deviancy is therefore, I believe, poorly founded.

A syntax formulated in terms of features (rather than subcategories alone) offers a different approach. We may now distinguish violations of categorial-component rules, as in (24); violations of rules of strict subcategorization, as in (25); and violations of rules of selection, as in (26). The number of rules violated in each expression could be counted, and a numerical coefficient of deviation computed for each sentence. Furthermore, if there should be reason to weight the rules violated (e.g. with reference to the order in which they appear in the grammar), a properly weighted coefficient of deviation would emerge. But although this approach is far more promising than the one described in the preceding paragraph, it does not yet differentiate between the deviations of (24)-(26) and those of (27). This could be done by postulating a hierarchy of syntactic-semantic features, so that (27) would be said to violate only features low in the hierarchy. It is unknown at this time whether a unique, consistent hierarchization of the semantic features of a language is possible. We develop an alternative approach to deviance in which the troublesome question of such a hierarchization loses a good deal of its importance.

Still another conception of deviance has been outlined by Katz (1964a). There it is argued that a semi-sentence, or ungrammatical string, is understood as a result of being associated with a class of grammatical sentences; for example, Man bit dog is a semi-sentence which is (partly?) understood by virtue of being associated with the well-formed sentences ‘ A man bit a dog ’, ‘ The man bit some dog ’, etc.; these form a ‘ comprehension set ’. The comprehension set of a semi-sentence, and the association between the semi-sentence and its comprehension set, are given by a ‘transfer rule’. However, the number of possible transfer rules for any grammar is very large: if a grammar makes use of n category symbols and if the average terminal string generated by the grammar (without recursiveness) contains m symbols, there will be (n— 1) x m possible transfer rules based on category substitutions alone; if violations of order by permutation are to be covered, the number of transfer rules soars, and if recursiveness is included in the grammar, their number becomes infinite.

The significant problem is therefore to find some criterion for selecting interesting transfer rules. Katz hopes to isolate those which insure that the semi-sentence is understood.

This proposal, it seems to me, is misguided on at least three counts. First, it offers no explication of ‘ being understood ’ and implies a reliance on behavioral tests which is illusory. Secondly, it assumes, against all probability, that speakers have the same abilities to understand semi-sentences, regardless of intelligence or other individual differences.5 Thirdly, it treats deviance only in relation to the hearer who, faced with a noisy channel or a malfunctioning source of messages, has to reconstruct faultless prototypes; Katz’s theory is thus completely powerless to deal with intentional deviance as a communicative device. But the overriding weakness of the approach is its treatment of deviance in quantitative terms alone; Katz considers how deviant an expression is, but not what it signifies that cognate non-deviant expressions would not signify.

1 On Bhartrhari, see Chakravarti (t933 : ii7ff.) and Sastri (1959: 245); unfortunately, neither source does justice to the subject. The Indian argument goes back at least to Patanjali (second century B.C.). See also Sibawaihi (1895: 10 ff.); Thomas of Erfurt (c. 1350: 47).

2 One is struck, for instance, by the similarity between a recent argument of Ziff’s (1964: 206) and a point made by the great Alexandrian, Apollonios, 18 centuries ago (Apollonios §iv. 3 ; ed. 1817 : 198). Ziff argues that the normality or deviance of It’s raining cannot depend on whether it is in fact raining when a token of the sentence is uttered. Apollonios contends that if a discrepancy between a sentence and its setting were classified as a (type of) solecism, the occurrence of solecisms would be limited to daylight conditions and to discourse with seeing persons, since the blind hearer, or any hearer in darkness, could not check a statement for its conformity with the setting.

3 The absence of a criterion is all the clearer in a syntax reformulated in feature terms.

Chomsky (1965) suggeststhat syntactic features maybe those semantic features which are mentioned in the grammar; but he provides no criteria for deciding when a grammar is complete vis- á -vis the dictionary.

4 For the sake of perspicuity, we have slightly simplified the original account - hopefully without distorting its intent.

5 This assumption is apparent from Katz’s criticism of another author’s approach to ungrammatically in which differing abilities of individual speakers may be involved (Katz 1964a: 415).

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)