Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-02-27

Date: 2024-05-10

Date: 2024-05-18

|

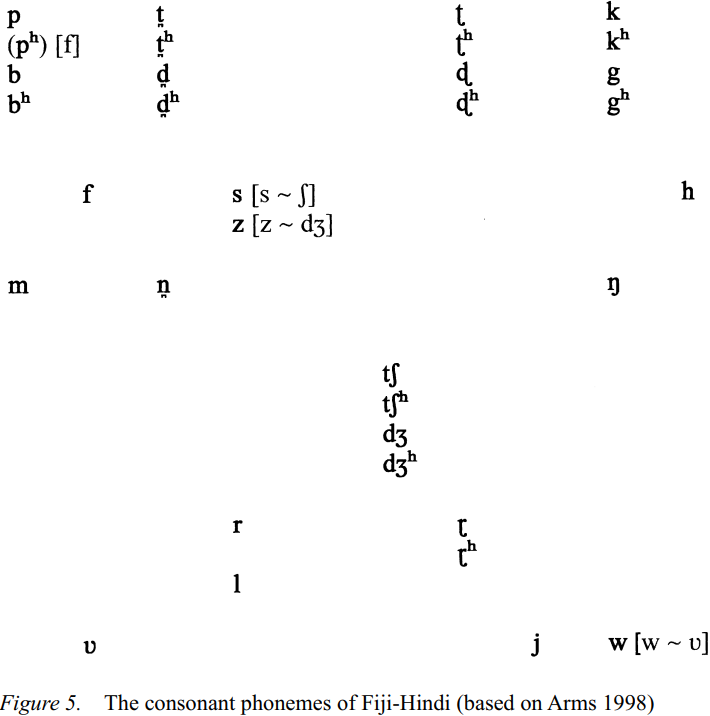

In order to understand the phonology of Pure Fiji English as spoken by Fiji’s Indo-Fijians, a brief overview of the phonology of Fiji Hindi is required. While it does not vary significantly from that of Standard Hindi (Siegel 1975; Moag 1977, 1979; Arms 1998), there are a few notable differences. Siegel (1975, 1987: 8) notes that for many Fiji Hindi speakers [ʋ] , [b] and [ph] and [f], [ʤ] and [z], and [ʃ] and [s] occur in free variation or an intermediate sound is used. Furthermore, [ɲ] , [ɳ] and [ŋ] are allophones of /n/ when preceding a consonant, and [l] is often replaced by [r] (Moag 1979), e.g. Fiji Hindi baar for Standard Hindi baal ‘hair’. On the other hand, Arms (1998: 2) claims that “[f] has completely replaced the primary [consonant] [ph]”. For example, we have [fu:l] for ‘flower’, rather than [phu:l]. Arms points out that this is also the case in some dialects of Hindi in India, while in others, the two sounds are in free variation. He adds that they are “certainly not in free variation in Fiji, but [f] has in some cases given way to unaspirated [p]”. He cites as examples [hapta] ‘week’ (rather than [hafta]) and [fuppa] ‘father’s sister’s husband’ (rather than [fuffa]) and notes that in the latter the initial [f] is retained while medially it has changed to [p]. He adds that “for some speakers the change of [f] to [p] takes place optionally in many vocabulary items.” Thus /f/ has become part of the phonemic inventory of Hindi – including Fiji Hindi – via three sources: Perso-Arabic loanwords, borrowings from English, and etymological /ph/. Arms also claims that [ʃ] has merged with [s] for many speakers, especially in rural areas.

The sounds which are used in Standard Hindi for the pronunciation of words of Perso-Arabic origin are not normally found in Fiji Hindi; neither are they in most colloquial varieties of Indian Hindi. For example, [z] is realized as [Ʒ] in Fiji Hindi, as in Colloquial Hindi (Bhatia 1995: 16), except in some proper nouns. This is true even among Indo-Fijian Muslims, whose lexicon includes more such words and who would use such words more often. Other examples include [x], which is realized as [kh], as in the name Khan, for instance. The same is true of the voiced counterpart, which is simply pronounced as a velar, rather than uvular, [g].

As for vowels, Hindi has a set of five pairs of vowels whose phonetic relationship is reflected in the Devanagari orthography. Three are pairs of short versus long vowels: /a/ and /a:/, /i/ and /i:/, and /u/ and /u:/. The mid vowels /e/ and /o/ are long and have not short vowels, but the diphthongs /ai/ and /au/ as their counterpart.

In Fiji Hindi long and short vowels do not always contrast. Siegel (1975: 130) claims that vowel length is not differentiated (especially [i] vs. [i:] and [u] vs. [u:]), and this seems particularly true in final position. Similarly, with the exception of a few monosyllabic words, the two diphthongs do not occur in word final position. In any case, they constitute only about 1% of all vocalic occurrences (Arms 1998: 3). It is unclear whether vowel nasalization, which occurs phonetically, is ever phonemic.

The consonant and vowel phonemes of Fiji Hindi are presented in Figures 5 and 6 respectively.

Although Standard and Fiji Hindi are phonologically similar, Pure Fiji English as spoken by Indo-Fijians differs from the “typical” Indian English of the sub-continent in a number of ways. For instance:

– Indo-Fijian English is, as a general rule, non-rhotic.

– Pure Indo-Fijian English has monophthongised diphthongs.

– The realization of alveolars as retroflexes is much less common in Indo-Fijian English, though some speakers of Pure Fiji English do exhibit this characteristic.

It is clear that much further empirical study needs to be carried both on the phonology of Fiji Hindi, and on the English spoken by Indo-Fijians. The following are the most common phonological features of Pure Fiji English as spoken by Indo-Fijians.

|

|

|

|

مخاطر خفية لمكون شائع في مشروبات الطاقة والمكملات الغذائية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"آبل" تشغّل نظامها الجديد للذكاء الاصطناعي على أجهزتها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلميّ يُواصل عقد جلسات تعليميّة في فنون الإقراء لطلبة العلوم الدينيّة في النجف الأشرف

|

|

|