تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

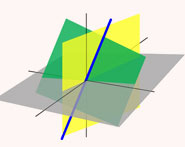

الهندسة

الهندسة

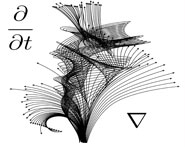

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 18-10-2015

Date: 20-10-2015

Date: 20-10-2015

|

Born: about 360 BC in Pitane, Aeolis, Asia Minor (now Turkey)

Died: about 290 BC

We know some information about the life of Autolycus of Pitane, but not really enough to date him accurately. He was a teacher of Arcesilaus who was born in 315 BC so Autolycus must have lived until after 300 BC. It is generally assumed that he was older than Euclid. As Heath writes in [3]:-

That he wrote earlier than Euclid is clear from the fact that Euclid ... makes use of theorems appearing in Autolycus, though, as usual in such cases, giving no indication of their source.

However, before we accept Heath's 'clear' argument, it is reasonable to put a counter argument from Neugebauer [4]:-

The generally accepted argument in favour of Autolycus's priority is singularly naive. Theorem 2 of Euclid's Phaenomena consists of four propositions with proofs for only three of them while the missing one is replaced by the remark "that this is the case has been shown elsewhere"; indeed theorem and proof are found as Theorem 10 in Autolycus's 'Rotating Sphere'. That a remark of this kind should be genuine in any Greek mathematical treatise, Euclidean or not, seems to me utterly implausible; I would assume the obvious, i.e. that a scholion replaced, perhaps in a damaged copy, the first of four proofs by a simple reference to generally known theorems. In fact I see no reason why Euclid (presumably in Alexandria) and Autolycus (presumably in Athens) should not have written independently, and perhaps even simultaneously, on the mathematical theory of astronomical phenomena.

Huxley, writing in [1], agrees with Heath, and the paper [4] even has the title Autolycus of Pitane, predecessor of Euclid. The priority argument is certainly not an unimportant one for the interdependence of Euclid and Autolycus on each other is significant since Autolycus writes his propositions in exactly the same general style as Euclid. This means that a theorem in Autolycus's work has first a general statement, then a construction related to a particular figure with points in the figure denoted by letters, next comes the demonstration of the theorem, and finally a conclusion relating to the general statement is sometimes drawn. Despite the arguments above, one must still draw the same conclusion whichever treatise was written first, namely that this style of mathematical exposition accepted today as so characteristic of Euclid, was certainly not invented by him. Despite the style being used by Autolycus, nobody credits him with inventing it either.

We have been taken down a fascinating road by the comparisons with Euclid, but we should return to give the only other detail of Autolycus's life which is reported by Diogenes Laertius, when he relates that Arcesilaus was accompanied by his teacher Autolycus on a journey to Sardis.

Another important fact regarding Autolycus is that two of his books have survived in the original Greek and we believe that they are the earliest two mathematics works to have survived. Of these books, On the Moving Sphere is a work on the geometry of the sphere which is the same as being a mathematical astronomy text. The second work On Risings and Settings is a book more on observational astronomy.

Theodosius, 200 years later, wrote Sphaerics, a similar book on the geometry of the sphere, also written to provide a mathematical background for astronomy. It is thought that Theodosius's Sphaerics and Autolycus's work On the Moving Sphere are based on the same pre-Euclidean textbook which is now lost. It is conjectured, on rather little evidence one would have to say, that Eudoxus wrote this earlier text. There seems to be no way in which the speculation on this point can ever be settled.

That Autolycus relys heavily on Eudoxus for his view of astronomy is not in doubt. He is a strong supporter of Eudoxus's theory of homocentric spheres which consisted of a number of rotating spheres, each sphere rotating about an axis through the centre of the Earth. This theory had a difficulty which had been quickly noticed, namely that Venus and Mars varied in brightness and there was no mechanism for this in Eudoxus's theory. Again eclipses of the sun were sometimes total, sometimes annular where moon appears smaller than the sun and a ring of the sun is visible right round the moon. Despite Autolycus's attempts to explain these observations within Eudoxus's theory, he had no real answer to these problems.

On Risings and Settings is a work which consists of two books. Schmidt's interesting article [7] was written to show that in fact these are not two parts of a single two volume work but rather they were both versions of the same piece of work. The second book is actually a revised and expanded edition of the first, which contains quite a bit of new material. It is also a better constructed book and it is interesting to see how Autolycus's book has developed and improved between the two editions.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|