Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Thematic roles

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

250-7

24-1-2023

3860

Thematic roles

We concluded that the argument structure of clauses is directly reflected in the internal syntactic structure of verb phrases. However, there is an important sense in which it is not enough simply to say that in a sentence such as (18b) The police have arrested the suspect the verb arrest is a predicate which has two arguments – the internal argument the suspect and the external argument the police. After all, such a description fails to account for the fact that these two arguments play very different semantic roles in relation to the act of arrest – i.e. it fails to account for the fact that the police are the individuals who perform the act (and hence get to verbally and physically abuse the suspect), and that the suspect is the person who suffers the consequences of the act (e.g. being manhandled, handcuffed, thrown into the back of a windowless vehicle and beaten up). Hence, any adequate account of argument structure should provide a description of the semantic role which each argument plays.

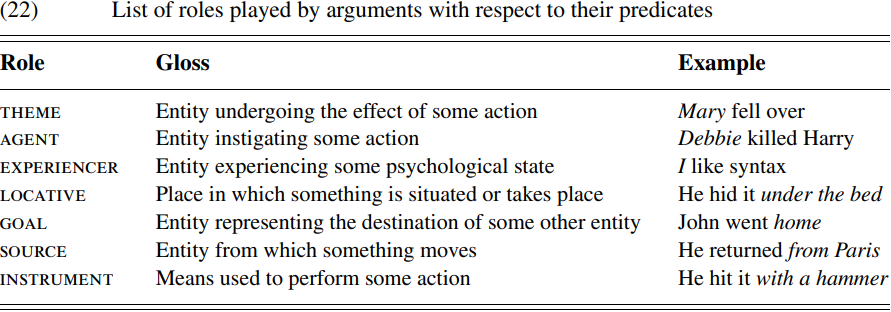

In research spanning half a century – beginning with the pioneering work of Gruber (1965), Fillmore (1968) and Jackendoff (1972) – linguists have attempted to devise a universal typology of the semantic roles played by arguments in relation to their predicates. In the table in (22) below are listed a number of terms used to describe some of these roles (the convention being that terms denoting semantic roles are CAPITALIZED), and for each role an informal gloss is given, together with an illustrative example (in which the italicized expression has the semantic role specified):

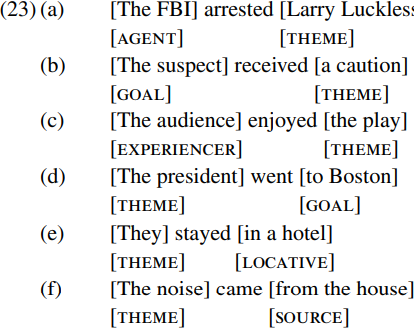

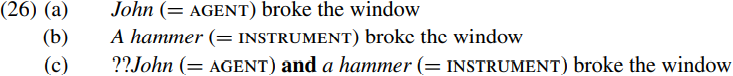

We can illustrate how the terminology in (22) can be used to describe the semantic roles played by arguments in terms of the following examples

Given that – as we see from these examples – the THEME role is a central one, it has become customary over the past two decades to refer to the relevant semantic roles as thematic roles; and since the Greek letter θ (= theta) corresponds to th in English and the word thematic begins with th, it has also become standard practice to abbreviate the expression thematic role to θ -role (pronounced theeta-role by some and thayta-role by others). Using this terminology, we can say (e.g.) that in (23a) the FBI is the AGENT argument of the predicate arrested, and that Larry Luckless is the THEME argument of arrested.

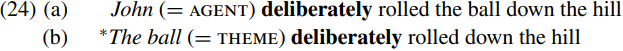

Thematic relations (like AGENT and THEME) have been argued to play a central role in the description of a range of linguistic phenomena. For example, it has been argued that the distribution of certain types of adverb is thematically determined. Thus, Gruber (1976) argues that adverbs like deliberately can only be used to modify AGENT arguments:

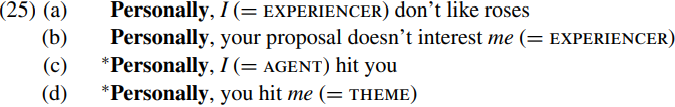

Likewise, Fillmore (1972, p. 10) argues that the adverb personally can only be associated with EXPERIENCER arguments:

In a similar vein, Fillmore (1968, p. 10) argues that only constituents with the same thematic function can be coordinated:

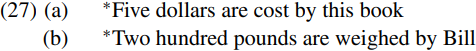

And Jackendoff (1972) argues at length that a number of constraints on passive structures can be accounted for in thematic terms. For example, he argues (1972, p. 44) that the ill-formedness of passive sentences like:

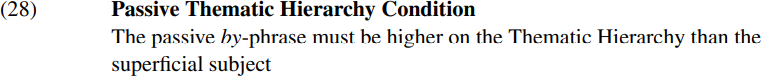

is attributable to violation of the following condition (formulated in thematic terms):

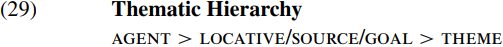

The hierarchy referred to in (28) is that in (29) below:

Jackendoff maintains that the by-phrase in both examples in (27) is a THEME argument of the relevant verb, whereas the superficial subject is a LOCATIVE argument. Since THEME is lower on the hierarchy (29) than LOCATIVE, sentences like (27) violate the condition (28) and so are ungrammatical.

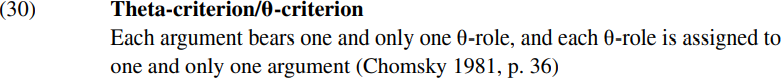

If we look closely at the examples in (23), we see a fairly obvious pattern emerging. Each of the bracketed argument expressions in (23) carries one and only one θ-role, and no two arguments of any predicate carry the same θ-role. Chomsky (1981) suggested that these thematic properties of arguments are the consequence of a principle of Universal Grammar traditionally referred to as the θ-criterion, and outlined in (30) below:

A principle along the lines of (30) has been assumed (in some form or other) in much subsequent work.

However, a question which arises from (30) is how θ-roles are assigned to arguments. It seems clear that in V-bar constituents of the form verb+ complement, the thematic role of the complement is determined by the semantic properties of the verb. As examples like (23a–c) illustrate, the associated with complements is often that of THEME (though this is not always the case – e.g. the complement me of the verb bother in Personally, it doesn’t bother me has the thematic role of EXPERIENCER). However, the question of how subjects are assigned θ-role is more complex.

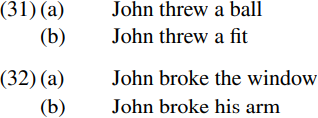

Marantz (1984, pp. 23ff.) and Chomsky (1986a, pp. 59–60) argue that although verbs directly assign θ-role to their internal arguments (i.e. complements), it is not the verb but rather the whole verb+ complement (i.e. V-bar) expression which determines the θ-role assigned to its external argument. The evidence they adduce in support of this conclusion comes from sentences such as:

Although the subject of the verb threw in both (31a) and (31b), John plays a different thematic role in the two sentences – that of AGENT in the case of threw a ball, but that of EXPERIENCER in threw a fit. Likewise, although the subject of the verb broke in both (32a) and (32b), John plays the role of AGENT in (32a) but that of EXPERIENCER on the most natural (accidental arm-breaking) interpretation of (32b). From examples such as these, Marantz and Chomsky conclude that the thematic role of the subject is not determined by the verb alone, but rather is compositionally determined by the whole verb+ complement structure – i.e. by V-bar. On this view, a verb assigns a θ-role directly to its internal argument, but only indirectly (as a compositional function of the semantic properties of the overall V-bar) to its external argument. To use the relevant technical terminology, we can say that predicates directly θ -mark their complements, but indirectly θ -mark their subjects/specifiers.

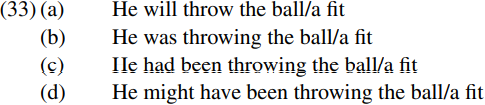

A related observation is that auxiliaries seem to play no part in determining the assignment of θ -roles to subjects. For example, in sentences such as:

the thematic role of the subject he is determined purely by the choice of V-bar constituent (i.e. whether it is throw the ball or throw a fit), and is not affected in any way by the choice of auxiliary. Clearly, any theory of θ-marking should offer us a principled answer to questions such as the following: how are θ-roles assigned? Why do some constituents (e.g. verbs) play a key role in θ-marking, while others (e.g. auxiliaries) do not?

We can provide a principled answer to these questions in the following terms. Let us assume that θ-roles are assigned to arguments via merger with a predicative expression (i.e. an expression headed by an item which functions as a predicate – e.g. a verb). In the light of this observation, consider our earlier sentence (18b) The police have arrested the suspect. Since the verb arrested is a predicate which selects a THEME complement, the complement the suspect will be assigned the θ-role of THEME argument of arrest when the verb merges with its complement. Since arrest is a predicate which (in addition to requiring a THEME complement) also requires an AGENT external argument, the subject the police will be assigned the θ-role of AGENT argument of arrest when it merges with the V-bar arrested the suspect. The resulting VP the police arrested the suspect is then merged with the auxiliary have to form the T-bar have the police arrested the suspect. Because a finite T has an [EPP] feature requiring it to have a specifier, the subject the police raises to spec-TP, deriving The police have the police arrested the suspect. However, the subject the police does not receive any θ -role from the auxiliary have, since auxiliaries are not predicates (unlike main verbs) and hence do not θ - mark their subjects. The resulting TP is ultimately merged with a null declarative complementizer to derive the structure associated with (18b) The police have arrested the suspect.

Our discussion here suggests that thematic considerations lend further support to the VP-Internal Subject Hypothesis. By positing that subjects originate internally within VP, we can arrive at a unitary and principled account of θ-marking in terms of sisterhood, in that an argument is θ-marked by a predicative expression which is its sister: e.g. the verb arrested in (21) θ-marks its sister argument (complement) the suspect, and the V-bar arrested the suspect θ-marks its sister (subject) argument the police.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)