Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Reflection: The role of prosody

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

211-7

23-5-2022

965

Reflection: The role of prosody

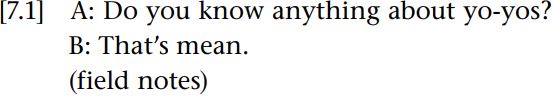

Brown and Levinson (1987) devote considerable attention to detailing output strategies, their exposition extends to approximately 150 pages. However, hardly any attention is devoted to how what is said sounds, how the prosody can influence politeness (or impoliteness) interpretations. Yet, it is not an unusual occurrence that people take offence at how someone says something rather than at what was said. Consider this (reconstructed) exchange between two pre-teenage sisters:

On the face of it, Speaker A’s utterance is an innocent enquiry about Speaker B’s state of knowledge. However, the prosody triggered a different interpretation. Speaker A heavily stressed and elongated the beginning of anything, coupled with marked falling intonation at that point (we might represent this as: “do you know ANYthing about /yo-yos?”). It signals to B that A’s question is not straightforward or innocent. It triggers the recovery of implicatures that Speaker A is not asking a question but expressing both a belief that Speaker B knows nothing about yo-yos (the prosodic prominence of anything implying a contrast with nothing), and an attitude towards that belief, namely, incredulity that this is the case − something which itself implies that Speaker B is deficient in some way. Without the prosody, there is no clear evidence of the interpersonal orientation of Speaker A, whether positive, negative or somewhere in between. Yet, despite the importance of prosody in communication, the vast bulk of research on politeness or impoliteness pays woefully little attention to the role of prosody. The single exception of note is the work of Arndt and Janney (e.g. 1987), whose notion of politeness involves emotional support conveyed multi-modally through verbal, vocal and kinesic cues (for prosody and impoliteness, see Culpeper 2011b).

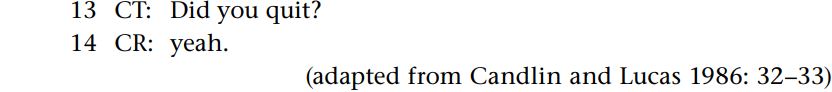

Brown and Levinson’s politeness theory has been applied, in full or part, to a wide variety of discourses, situations and social categories, including “everyday” conversation, workplace discourse, job interviews, healthcare discourse, political discourse, media discourse, literary texts, historical texts, gender and conflict, not to mention a huge literature examining intercultural or cross-cultural discourses. For the purposes of exemplifying the kind of analysis that can be done, we will examine an example of healthcare discourse. Our data is taken from Candlin and Lucas (1986), where politeness issues are in fact only very briefly touched on. The lineation has been slightly changed. The context is an interview at a family planning clinic in the USA. CR is a counsellor, who interviews clients before they see the doctor. CT is a client, who is pregnant.

CR’s goal is to get CT to stop smoking. She repeatedly uses the speech act of request. However, this request is realized indirectly. A very direct request might be “quit smoking”. In contrast, in turn 1 her request is couched as a question about whether CT has ever thought about stopping, and in turn 3 it is a question about what CT thinks of her ability to stop. This does not meet with success, so in turn 5 CR tries another tack, engaging CT in talk about a possible cause of the smoking, rather than directly talking about stopping. Then in turn 7 CR links the cause to cutting down. Note how indirect this is: it is phrased as a question about whether she has thought about whether she would be able to cut down. CR’s strategy thus far is largely off-record politeness: by flouting the maxim of Relation (it is improbable in this context that CR is only inquiring about CT’s thoughts) and the maxim of Quantity (what is to be cut down is not specified), she leaves it to CT to infer that she is requesting her to stop smoking (i.e. CR’s implicature).2 Turn 7 is further modified by hedging the possibility that she has the ability to cut down (cf. might), and making it conditional (cf. if you worked on those things). These linguistic strategies – conditionals and hedges – are the stuff of negative politeness. Note that a downside of this kind of indirectness is the loss of pragmatic clarity. In turn 2 CT either chooses to ignore or possibly was not aware of CR’s implicature requesting her to stop, and just replies to the literal question (I’ve thought about it). Similarly, after turn 7 CT either exploits or is simply confused by the lack of clarity regarding what she should cut down (on the stress you mean). In turn 9 CR probes what the reasons for not giving up might be. The frequent hesitations signal tentativeness, a reluctance to impose, and thus can be considered a negative politeness strategy. In the final part of that turn, she again uses a question, but notably she refrains from completing the question and spelling out the other half of the if-structure (i.e. if the stress is eliminated, the smoking will be). This could be considered an example of don’t do the FTA. Thus far, CR does not seem to be making much progress with her goal, and in the following turns (not presented in the text above) she makes only minimal responses. In turn 12 CR tries a completely different tack. She not only self-discloses (I’ve got my bad habits too ... I’ve smoked for eight years too so I know it’s not easy), but reveals information that (a) is negative about herself, and (b) is something that she has in common with CT. The kind of strategy in (a) is not well covered in Brown and Levinson, but could be accounted for by Leech’s Modesty maxim (minimize praise of self/maximize dispraise of self); the strategy in (b), claiming common ground, is an example of positive politeness. Importantly, note the effect of this on CT. For the first time, CT has engaged CR in conversation: instead of simply responding in a fairly minimal way, she asks a question (Did you quit?).

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)