تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

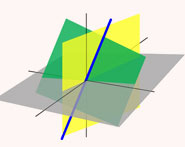

الهندسة

الهندسة

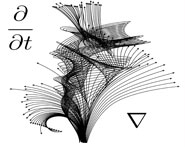

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 13-5-2022

Date: 27-2-2022

Date: 10-3-2022

|

The happy end problem, also called the "happy ending problem," is the problem of determining for

Since three noncollinear points always determine a triangle,

Random arrangements of

Random arrangements of

As the number of points

Erdős and Szekeres (1935) showed that

|

(1) |

where

|

(2) |

by Chung and Graham (1998),

|

(3) |

by Kleitman and Pachter (1998), and

|

(4) |

by Tóth and Valtr (1998). For

The values of

Borwein, J. and Bailey, D. Mathematics by Experiment: Plausible Reasoning in the 21st Century. Wellesley, MA: A K Peters, p. 78, 2003.

Chung, F. R. K. and Graham, R. L. "Forced Convex

Erdős, P. and Szekeres, G. "A Combinatorial Problem in Geometry." Compositio Math. 2, 463-470, 1935.

Hoffman, P. The Man Who Loved Only Numbers: The Story of Paul Erdős and the Search for Mathematical Truth. New York: Hyperion, pp. 75-78, 1998.

Kleitman, D. and Pachter, L. "Finding Convex Sets among Points in the Plane." Discr. Comput. Geom. 19, 405-410, 1998.

Lovász, L.; Pelikán, J.; and Vesztergombi, K. Discrete Mathematics, Elementary and Beyond. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2003.

Sloane, N. J. A. Sequence A052473 in "The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences."Szekeres, G. and Peters, L. "Computer Solution to the 17-Point Erdős-Szekeres Problem." ANZIAM J. 48, 151-164, 2006.

Tóth, G. and Valtr, P. "Note on the Erdős-Szekeres Theorem." Discr. Comput. Geom. 19, 457-459, 199

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|